I am sure by now you are well aware of the record-breaking winter that California just experienced! To put this into perspective, the high terrain of California’s current snowpack is in the range of 195% to 300% of the normal average for this time of the season. Even more interesting is the snow water equivalent (amount of water locked up in the snowpack) is ~58 to 64 inches. If you were to melt it, then it would be over 4.5 feet of water. WOW!

So, this leads to a big and curious question: How come California just set records despite a La Niña winter, when usually El Niño winters are favorable for high rates of precipitation? Before I jump into this and bring up some thought-provoking questions, let’s quickly dive into a little Atmospheric Science 101 and break down these common climate pattern phenomena you’ve probably heard before and how they impact the weather we experience throughout the seasons.

To begin, what exactly is a La Niña and an El Niño? Essentially, these are climate patterns of the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) that originate in the Pacific Ocean thus impacting global weather. Think of La Niña as the cooling of the ocean surface and El Niño as the warming of the ocean surface.

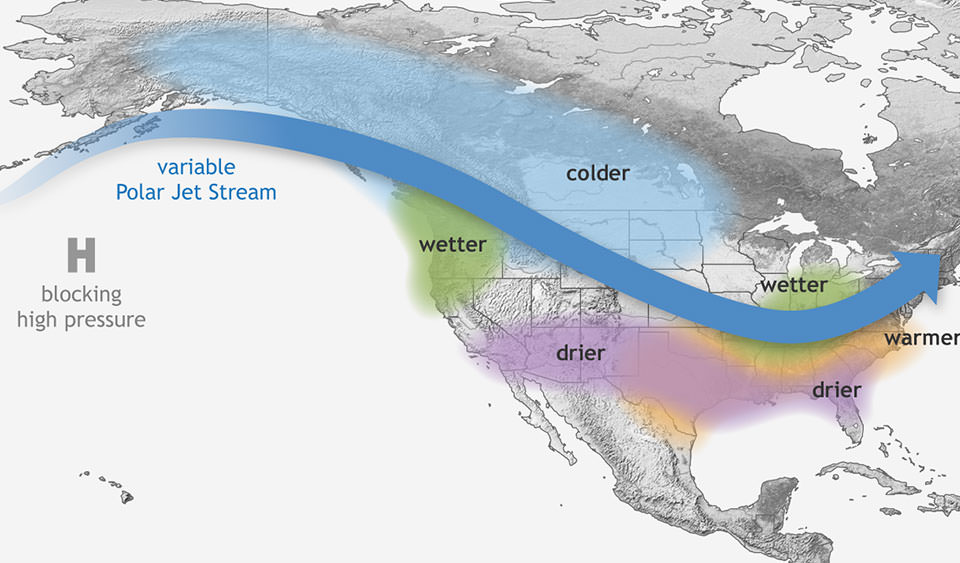

During a La Niña season, as you can see from the image above, the jet stream tends to favor Northern California and the Pacific Northwest (Oregon, Washington, and BC). The central and southern Sierras of California tend to miss out on this jet stream track of moisture potentially resulting in below-average precipitation. Classic La Niña conditions consist of wet and colder-than-normal winter temperatures for the PNW. The intensity of a La Niña is directly tied to the sea surface temperatures (SST), which range from -0.5 C to -1.5 C below the average across the eastern and equatorial Pacific Ocean.

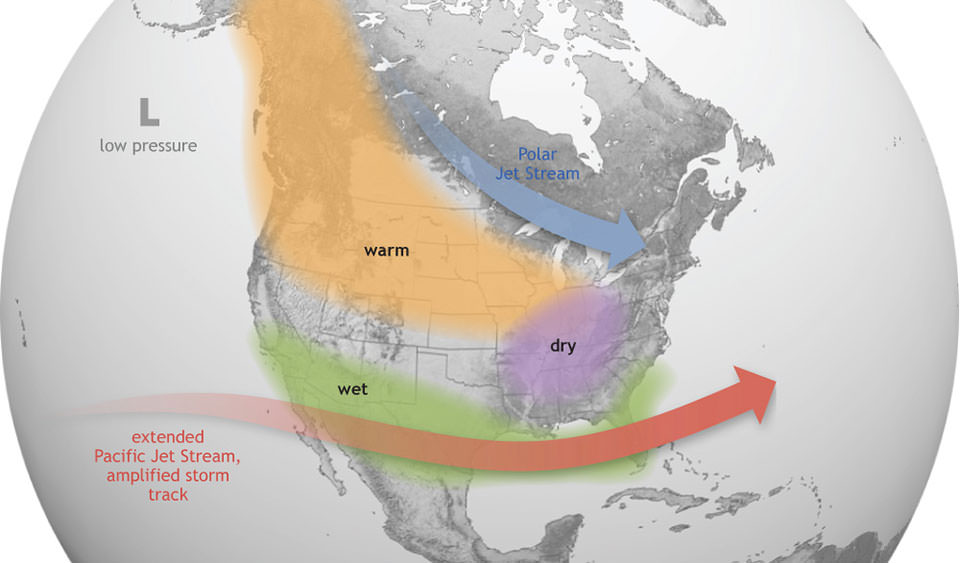

During an El Niño season, as you can see from the image below, the jet stream tends to favor the central and southern Sierras of California, Arizona, New Mexico, etc. Northern California and the Pacific Northwest (Oregon, Washington, and BC) tend to miss out on this jet stream track of moisture potentially resulting in below-average precipitation. Classic El Niño conditions consist of dry and above-normal winter temperatures for the PNW. The intensity of an El Niño is directly tied to the sea surface temperatures (SST), which range from 0.5 C or greater across the eastern and equatorial Pacific Ocean.

You are probably curious about what an Atmospheric River is. Essentially, an atmospheric river (AR) is a large plum of moisture stretching from the tropics that produces a huge amount of precipitation in the form of rain for the lowlands and heavy snow for the high terrain. ARs are typically around 250 to 375 miles wide. The strongest AR events tend to be more damaging and volatile than beneficial.

Now that you have a solid basis for the difference between these two climate patterns as well as atmospheric rivers, let’s contemplate and explore the BIG and open-ended question: Why did Northern California and especially the Central and Southern Sierra just experience a record-breaking winter season despite La Niña conditions?

The one factor likely driving the intensity and severity of these atmospheric rivers is climate change. Essentially as our atmosphere continues to warm, this warmth has the potential to ramp up how extreme these weather events play out along the West Coast. To put it in simpler terms, having a warmer atmosphere translates to atmospheric rivers being able to mold more moisture, thus making these “river in the sky” events more damaging and destructive versus beneficial for drought and reservoir build-up.

To bring this into full view, climate models are suggesting a moderate to strong El Niño is in store for the West this coming fall and winter. Do you think this will translate to another historic upcoming winter for the high terrain in California? Or will it go against the flow (pun intended) and lead to big snow for the Oregon/Washington Cascades and BC?!

Another idea to mention is the larger sways in variability meaning there is a strong chance we will see more extreme shifts in heavy precipitation and drought periods being magnified because of climate change. I also want to emphasize that there has always been variance and change in the climate on this planet. However, it’s the rate at which things are being warmed up across the globe that is of deep concern. Climate change, as we are experiencing it, is not normal and effectively disrupts the earth’s natural equilibrium.

What are your thoughts on this complex and fascinating matter? Do you think California will have a winter like it just did this 2022/2023 season or will it be decades before a winter like it happens again?