Mammoth Mountain. January 14th. I was sitting in a gondola being carried to heaven: I was going to the best bluebird day of my snowboarding career after a week of storms dropped around 20 feet of snow. After I landed, I skated to an untouched spot, arriving breathless and exhausted. I powered through and dropped in. The snow was magical, but, true to its Sierra Cement nickname, half way through and my weak legs gave their everything to keep me upright. I had to stop and sit. My breath was so fast that I couldn’t catch up with it. My head started to hurt and the light seemed brighter than ever before. I thought I wouldn’t be able to go any further, but I got to the bottom. In a hasty delusion, I made the mistake of walking the half mile or more to my car instead of waiting for the bus. I felt like I was in the middle of the Sahara, out of water, equally exhausted and shriveled, about to pass out under the sun. Worse, my stomach was bubbling with acid and I was afraid I wouldn’t keep it down. And just like that, my first run became my last and the untouched snow was ruined by the next day.

What I experienced aligns with acute mountain sickness, in other words: the lowest end of the altitude sickness spectrum. Even though it was awful and kept me from a perfectly good day of riding, the acute stuff is nothing compared to the heavy-duty stuff: aka HAPE, which can cause death within hours of accent.

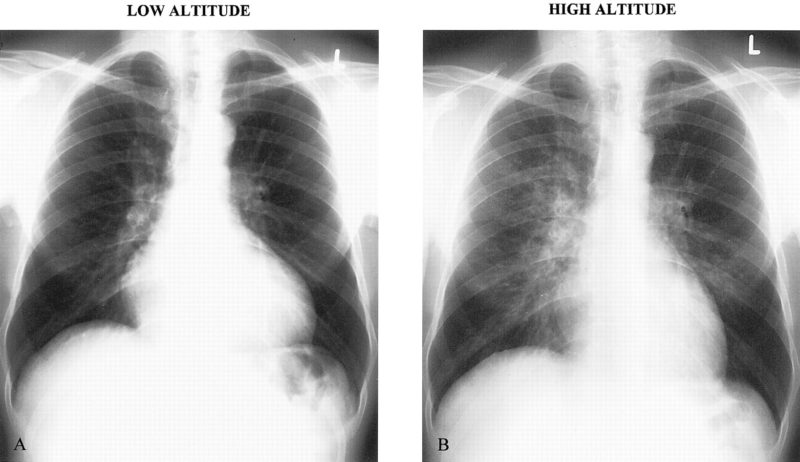

HAPE, high-altitude pulmonary edema, becomes a threat around 8000ft or 2500m. Anyone can fall victim to HAPE, or any altitude sickness, regardless of their fitness levels or age. In fact, there is no certainty about who will and who will not be effect by the reduction in oxygen. However, scientist hypothesize groups most likely to be effected. They are: those who engage in aggressive exercise in the first few days; those who have had altitude sickness before; those who are obese; and, possibly, those who have a bad altitude-ascending-gene. At its core, HAPE causes fluid to fill the lungs. This happens at rapid altitude gain because the low oxygen concentration causes the blood vessels in the lungs to tighten, leading to lung arteries and leaking fluid AKA death by flooded lungs. The scariest part: this can happen without any other triggers or signs of altitude sickness (it may only be accompanied by the totally obvious sign of fatigue) AND it worsens at night, just as you’re getting your fatigued little head to bed. How’s that for a peaceful mountain vacation?

Now that I’ve got your attention and anxiety levels up, let me tell you how to prevent dying the first day on the hill. First: LISTEN TO YOUR BODY. As told by altitude.org, “It is never normal to feel breathless when you are resting – even on the summit of Everest.” This might be the only sign you get for HAPE, so take extreme breathlessness seriously. If you cough and subsequently froth white or pink, you probably contracted HAPE. A fever, blue lips, and increased heart rate will most likely follow. You shouldn’t let it get that far, though. Harvard Health recommends at the point of extreme exhaustion or breathlessness to descend immediately. A doctor should be called as soon as possible, especially if conditions worsen at lower elevation. Treatment will include oxygen and nifedipine and possibly a bit of time in the hyperbaric chamber.

Don’t risk powder days or your life: take the first few days above 8,000’ slow, drink plenty of water, and have ibuprofen ready for mild headaches.