It was a cold, brisk, Saturday morning as Ryan flew up the skin track, eager to reach the summit. Bogged down from a stressful week in the office, Ryan had left his house in San Francisco that morning and headed to Tahoe for a refreshing day in the backcountry with his friend, Mike. However, something was wrong, and Ryan didn’t feel as strong as he usually did. As they began to ascend, Ryan began to experience shortness of breath, but he quickly shrugged this off as it was his first day of the season and he had fallen quite out of shape. However, as they ascended higher and higher, Ryan’s shortness of breath became worse, and he began to develop a cough and tightness in his chest. Ryan was experiencing some of the first symptoms of high-altitude pulmonary edema (HAPE), the most common cause of death related to exposure to high altitudes.

Fortunately, Ryan had read an article on SnowBrains the night before and was able to recognize his symptoms and ski back down before it was too late. Should Ryan have continued his ascent, he likely would have begun to develop more symptoms of HAPE including difficulty breathing at rest, Tachycardia (rapid heart rate), crackling noises in the lungs, poor coordination, altered consciousness, and in severe cases, death.

HAPE most commonly occurs in people who live at low elevations and rapidly ascend to a higher altitude (usually 8,200 ft+). Other factors that can contribute to HAPE include sex (males are more likely to develop HAPE than females), genetic factors, prior development of HAPE, cold exposure, intensity of physical activity, underlying medical conditions such as pulmonary hypertension, and anatomic abnormalities. While these factors can increase susceptibility, HAPE is especially dangerous because it can occur in healthy and in shape individuals.

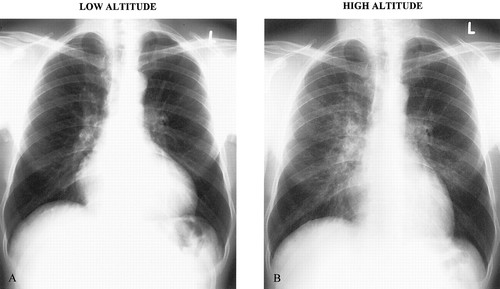

While HAPE still isn’t fully understood, the most popular theory is that as the person ascends, blood vessels in the lungs constrict, causing an increase in pressure. As the pressure builds, fluid leaks from the blood vessels into the alveoli, the small sacks in the lungs in which gas exchange occurs. This is what causes the shortness of breath and can lead to mortality if not treated quickly.

The best way to avoid HAPE is through taking preventative measures. Since HAPE is most commonly caused by a rapid increase in elevation, it is best to ascend gradually. The Wilderness Medical Society (WMS) recommends that above 9,800 feet, sleeping elevation should not be increased by more than 1,600 feet per day. In addition, a rest day should be taken every 3-4 days, and before or after large gain days. For those more susceptible to HAPE, Nifedipine, a pulmonary vasodilator drug that relaxes blood vessels, can be taken one day before a large ascent and continued throughout the high altitude excursion. Alcohol and sleeping medications should also be avoided.

If preventative measures fail, the best treatment for HAPE is to descend to a lower elevation. Any descent at all can be beneficial, but symptoms don’t usually become noticeably better until descending at least 1,650 feet. HAPE can also be treated with the drug Nifedipine. In less severe cases, descent might not be necessary and HAPE can be treated with warming, rest and supplemental oxygen.

HAPE is the most deadly high altitude related illness and it is important for all of us outdoor enthusiasts to know and understand all of the symptoms, causes, and treatments. While it can be frustrating to turn back with the summit in sight, it is always better to be safe than sorry. Those mountains aren’t going anywhere and can always be bagged another day.