I love the snow. It makes me smile. It is what I dream about when my head hits the pillow at night. I fell in love at the base of Mount Mansfield in the middle of an unexpected snowstorm. Whenever I can, I leave the city and find solace in the wintery landscape of the northern Vermont mountains. Even in the city, I love the crunch of fresh snow beneath my boots, the way that a blanket of snow diffuses the urban soundscape. While the same element that creates such wonder in many can also cause chaos, destruction even, no one can deny the quiet beauty of freshly fallen snow.

WILSON A. BENTLEY, THE ‘SNOWFLAKE MAN’

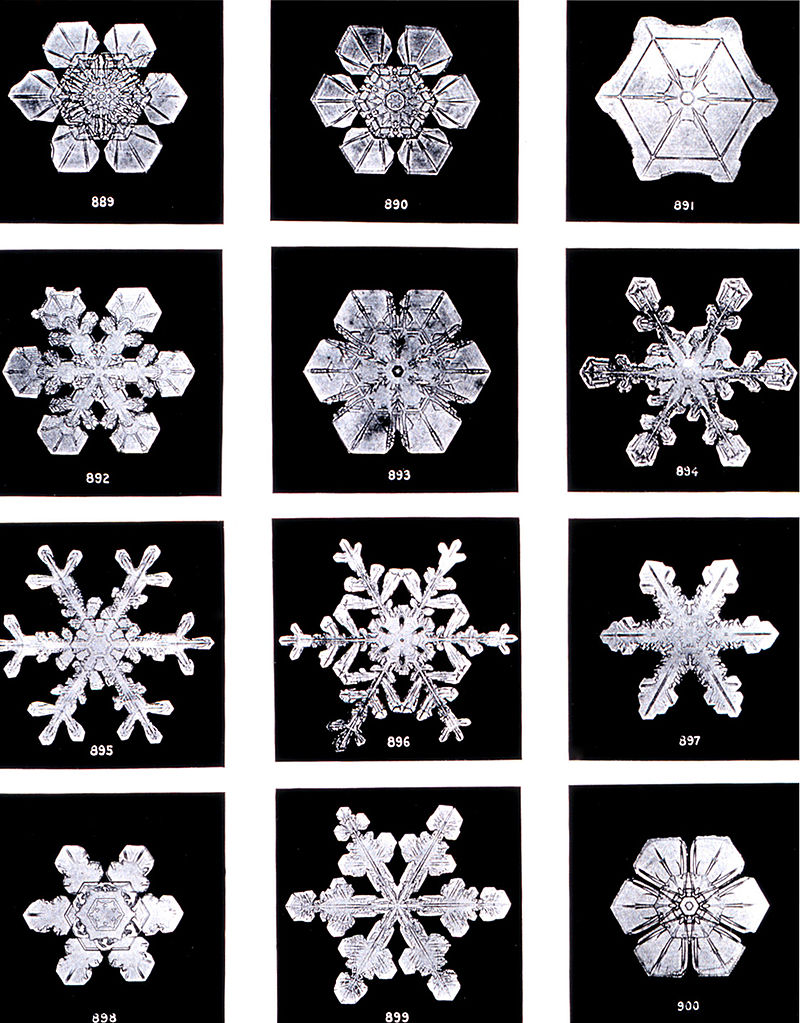

“Under the microscope, I found that snowflakes were miracles of beauty; and it seemed a shame that this beauty should not be seen and appreciated by others. Every crystal was a masterpiece of design and no one design was ever repeated., When a snowflake melted, that design was forever lost. Just that much beauty was gone, without leaving any record behind.”

-Wilson A. Bentley, Jericho, Vermont

Have you ever wondered how snowflakes form? Wilson A. Bentley did. Wilson (1865–1931), who became fascinated with snowflakes as a teenager on his family’s farm in rural Jericho, Vermont, pioneered work that still informs modern philosophy and science surrounding snowflakes. Adapting a microscope to a bellows camera, he was the first person to photograph a single snow crystal in 1885, and over the years became internationally recognized for his work. Perfecting a technique of catching snowflakes on black velvet in such a way that their images could be captured before they melted, in his lifetime Bentley photographed more than five thousand snowflakes. In collaboration with George Henry Perkins, a professor of natural history at the University of Vermont, he published an article in which he argued that no two snow crystals were alike, an idea that captured the public imagination. In 1931 Bentley published his life’s work, a monograph illustrated with over 2,500 photographs of snowflakes.

DEEPER INTO SNOWFLAKE SCIENCE

So how do these symmetrical structures that Bentley so vividly captured fall from the sky, and why is it that no two snowflakes are alike? A snowflake forms when a cold-water droplet freezes onto a pollen or dust particle, creating an ice crystal. As the ice falls to the ground, water vapor freezes onto the primary crystal, forming new crystals – the six arms of the snowflake. The crystals that make up snowflakes are symmetrical because they reflect the internal order of the crystal’s water molecules as they arrange themselves in predetermined spaces to form a six-sided snowflake. Temperature determines the basic shape of the ice crystal. The intricate shape of a single arm of the snowflake is determined by the atmospheric conditions experienced by the entire crystal as it falls. A crystal might begin to grow arms in one way, and then minutes later, slight changes in the surrounding temperature cause the crystal to grow in another way. The six-sided shape is always maintained, and because each arm experiences the same atmospheric conditions, the arms look identical. Individual snowflakes look unique because they all follow slightly different paths from the sky to the ground, encountering slightly different atmospheric conditions along the way.

SNOW SCIENCE TODAY

How the beauty of a single snowflake captures our attention hasn’t changed, but the science – snow hydrology – of snow has evolved with the times. By studying snow, where it forms, where it falls, and how the snowpack changes, snow scientists contribute to more accurate storm forecasting. They study snow cover to understand how changes in snow affect climate, glaciers, and water supply globally. They look at snowflakes to determine the stability of the always-dynamic snowpack and know that surface snow that breaks quickly and cleanly is more likely to form an avalanche than snow that breaks slowly or roughly. They use sensitive microscopes in a lab environment to see how shape affects a snow crystal’s ability to bond to other crystals. They look at seemingly more mystical properties of snow, like how the age of snow can affect how sound waves travel; an evolution in science starting with one man’s fascination with perfect crystals falling from the sky and blanketing the earth, and the idea that no two snowflakes are alike.

We get it you like snow