Brought to you by 10 Barrel Brewing

Report from December 23, 2020

We went a-walkin’ around in the Teton Mountain Range, WY today.

We skied a chute that had mostly great snow with a few crunchy spots.

We then skied another chute with really tricky snow – lots of punchy snow and some icy patches that weren’t obvious that really threw us off our game.

Had we done the second chute first, we likely wouldn’t have skied another lap.

Overall, a very fun day in the backcountry.

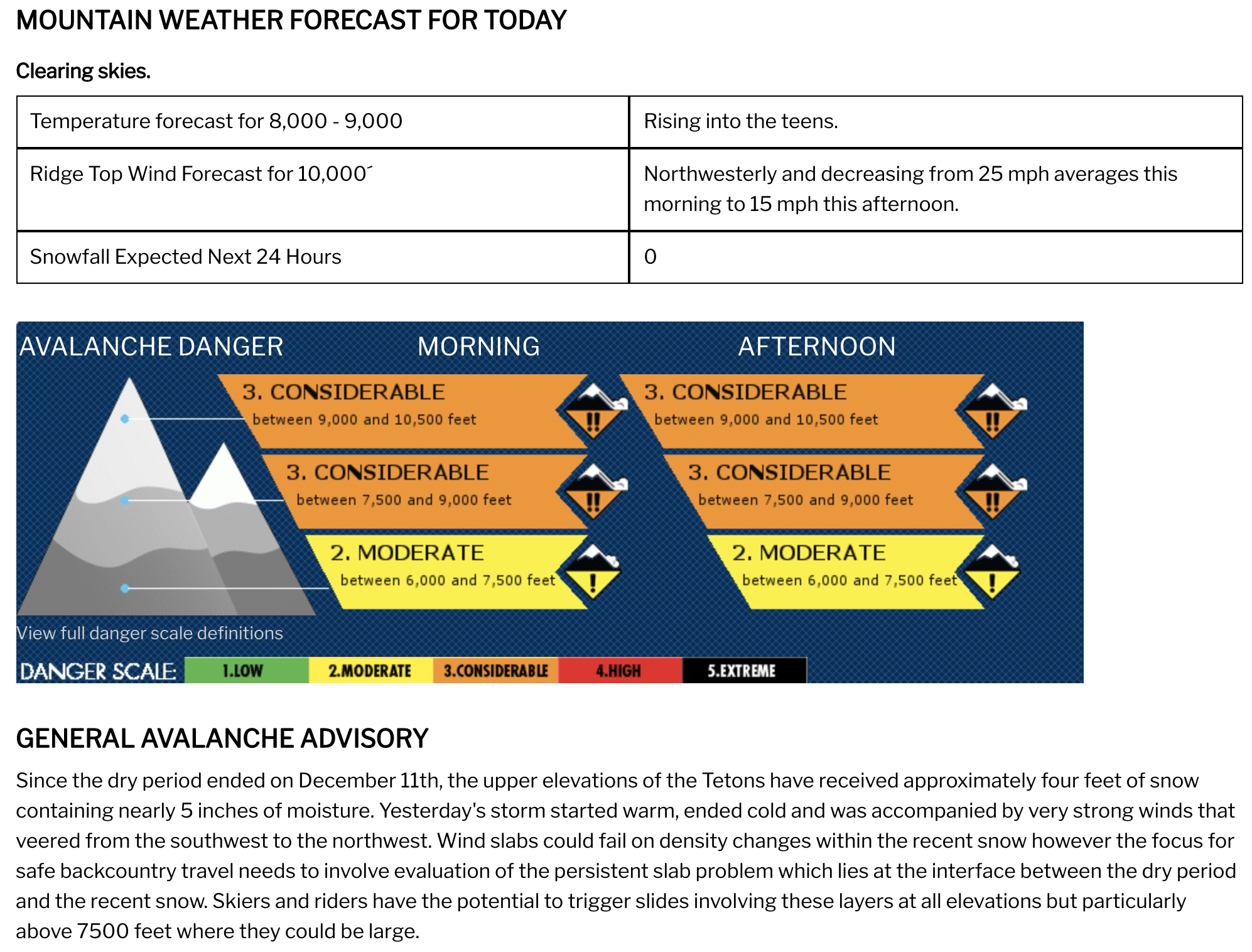

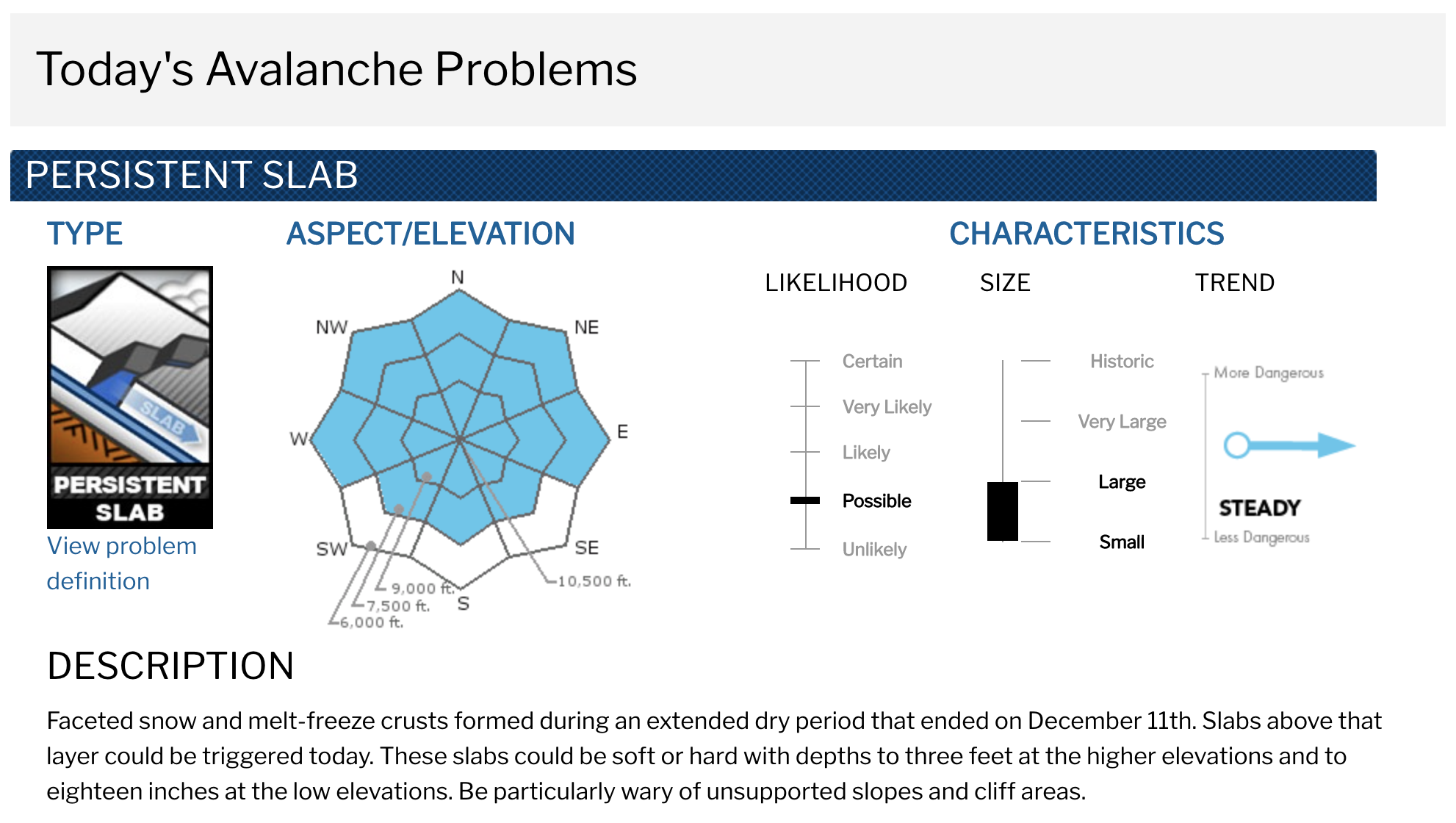

Since the dry period ended on December 11th, the upper elevations of the Tetons have received approximately four feet of snow containing nearly 5 inches of moisture. Yesterday’s storm started warm, ended cold and was accompanied by very strong winds that veered from the southwest to the northwest. Wind slabs could fail on density changes within the recent snow however the focus for safe backcountry travel needs to involve evaluation of the persistent slab problem which lies at the interface between the dry period and the recent snow. Skiers and riders have the potential to trigger slides involving these layers at all elevations but particularly above 7500 feet where they could be large.

Avalanche Terrain Decision-Making Process Today:

Many people have been asking me to explain my decision-making process when skiing avalanche terrain. Below is my first stab at it. When skiing/riding in avalanche terrain, there is always risk. To avoid avalanche risk, keep your terrain choices below 30º of steepness and learn how to accurately measure terrain steepness. Always check the forecast at avalanche.org. Always bring beacon, probe, shovel, education, experience, and a strong partner.

Why I felt comfortable skiing an aggressive chute today in CONSIDERABLE to MODERATE avalanche conditions:

- I dug several hand pits and tested snow columns and found the new snow well-bonded to the ice layer underneath where I believe the instability problem existed today.

- I performed 2 ski cuts at the top of the chute (generally where the greatest avalanche danger lies from wind loading in a chute) and the snow appeared stable.

- The chute’s entrance lies below 9,000′ and is not near a ridgeline giving it less opportunity to wind-load via the ridgetop winds.

- The chute was small making it a relatively isolated terrain feature which would have resulted in a relatively small avalanche had it fractured – ie, I don’t think it would have buried a person if it slid. However, had I been caught and carried in even a small avalanche in this chute the opportunity for trauma would have been high given the many features in the chute: rocks, trees, stumps, rock walls.

- I had identified several “safe zones” in the chute where I could have potentially pulled out of the chute to allow an avalanche to pass had I started one. The trick is being aware that an avalanche has occurred earlier enough to make this type of move – hence the 4 “look-backs” in the first part of the chute (and this was likely a bit of over-confidence on my part as it’s very difficult to ski out of an avalanche).

- I had recently skied this chute and knew the terrain.

- Friends skied this chute yesterday and I had information from them as well as video and they didn’t see signs of instability in the chute (the chute had refreshed with new snow and blowing snow since yesterday so this information had a lower value today).

Red flags in this chute today:

- Recent snowfall

- Recent windblown snow

- Over 30º of steepness

Avalanche Observations:

- I saw 5 wet avalanches that occurred in the recent rainy cycle – December 20-21, 2020

- I didn’t see any other signs of instability today

Avalanche Forecast:

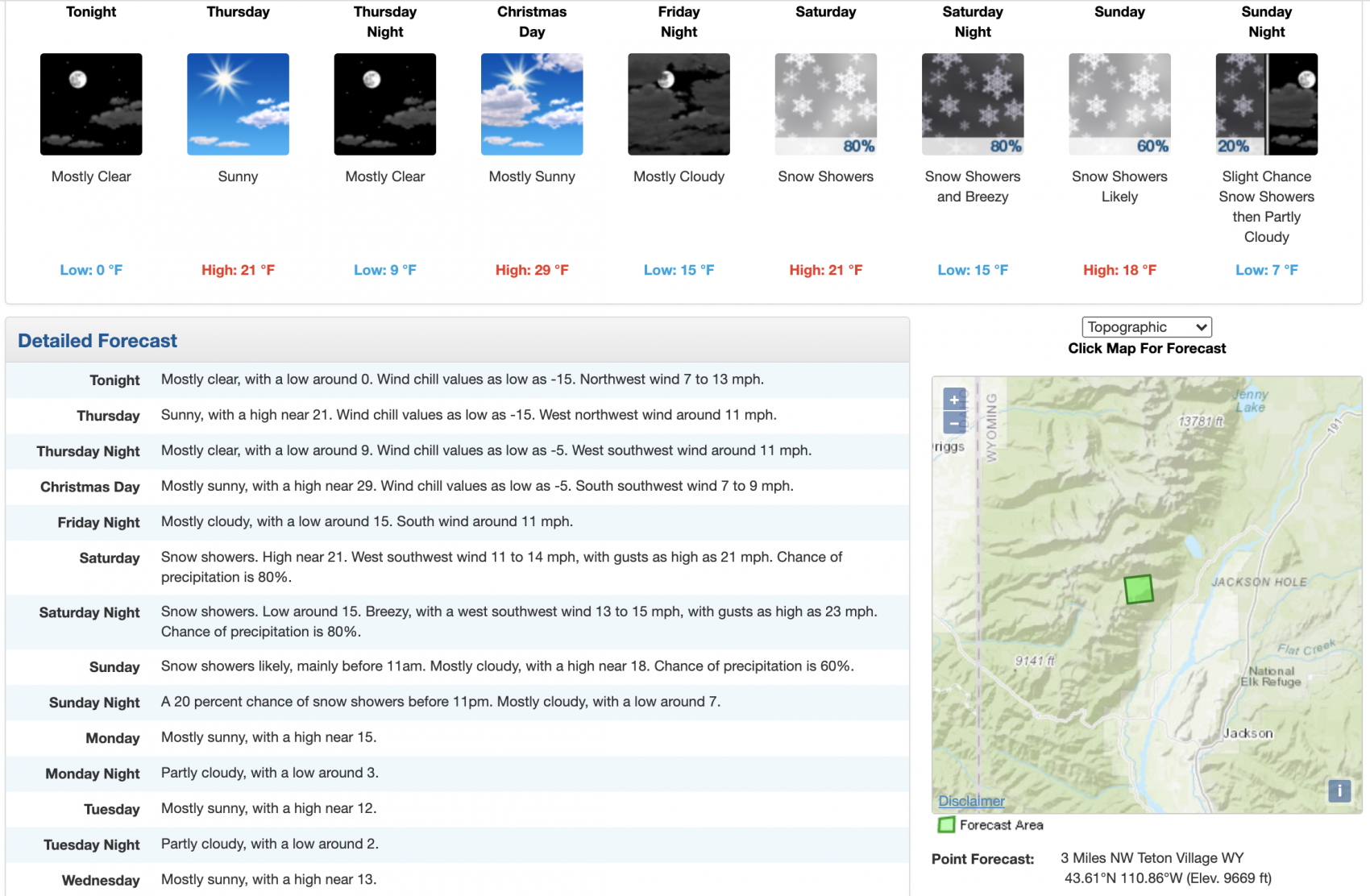

Weather Forecast

And not heuristic at all which is so good to see in this day and age and on this bloggggggg