A Summer of Fire-Breathing Smoke Storms first appeared on NASA Earth Observatory and was written by Adam Voiland.

In 2000, atmospheric scientists from the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory (NRL) first reported that smoke plumes from intense wildfires could spawn towering thunderstorms that channeled smoke as high or higher than the cruising altitude of jets. These pyrocumulonimbus, or pyroCb, events wowed scientists at the time. Prior to that discovery, only explosive volcanic eruptions and extreme thunderstorms were thought to be capable of lofting material so high.

Though the workings of these smoke-infused storm clouds have come into clearer focus, their increasingly extreme behavior in recent years has surprised and worried some scientists who track them. The latest encounters with these fire-breathing smoke clouds came in North America in June and July 2021 during an unusually warm fire season that arrived early in Canadian and U.S. forests.

Michael Fromm and David Peterson of NRL and a team of colleagues from NASA and several other institutions have used the Advanced Baseline Imager (ABI) on the NOAA-NASA GOES weather satellites, as well as sensors on other satellites, to identify 61 pyroCbs in North America this year as of July 29, 2021, about the halfway point of the fire season.

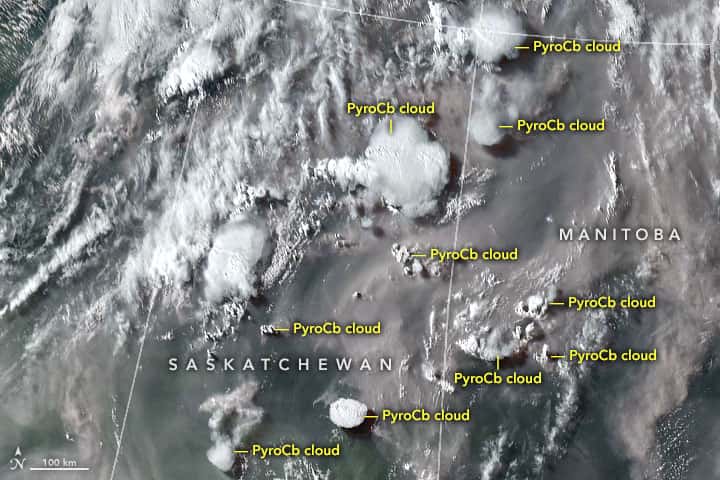

Their observations included a remarkable outbreak of 10 pyroCbs along the Saskatchewan-Manitoba border on July 16. It was more of the wildfire smoke storms than scientists have ever observed in North America on a single day since they started tracking all of them with satellites in 2013. In the ABI image shown above, all of the marked clouds ended up generating PyroCbs, though some were still in the pyrocumulus (pyroCu) stage when the image was taken. The image below shows an example of a small pyroCb rising above the McKay Creek fire on June 30, 2021.

The July outbreak came two weeks after another unusual event—what Fromm called a “monster pyroCb” that exploded on June 30 above the Sparks Lake fire in western Canada. A storm cell grew over a forest fire in British Columbia and spread across more than 160,000 square kilometers (62,000 square miles), an area slightly larger than the state of Georgia.

As it spread out, it sent a chimney of smoke up to 16 kilometers (10 miles), according to data collected by the Multi-angle Imaging SpectroRadiometer (MISR) on NASA’s Terra satellite. Meanwhile, a GOES satellite observed the storm unleashing extraordinary bursts of lightning. After watching satellite clips of the storm blowing up and smoke spreading widely as updrafts hit the stratosphere, one meteorologist characterized the cloud’s behavior as “absolutely mind-blowing.”

Scientists say it was the largest single pyroCb cloud they have ever observed in North America. The North American Lightning Detection Network recorded nearly 113,000 cloud-to-ground lightning strokes during the event, a large amount for a storm in Canada. One meteorologist calculated that this one pyroCb event produced about 5 percent of Canada’s total annual lightning all at once. Because smoke particles in pyroCbs limit the size of water droplets, the thunderstorms produce minimal rain. So the burst of lightning may have sparked new fires, accelerated their spread, and re-energized the meteorological engine that created it in the first place.

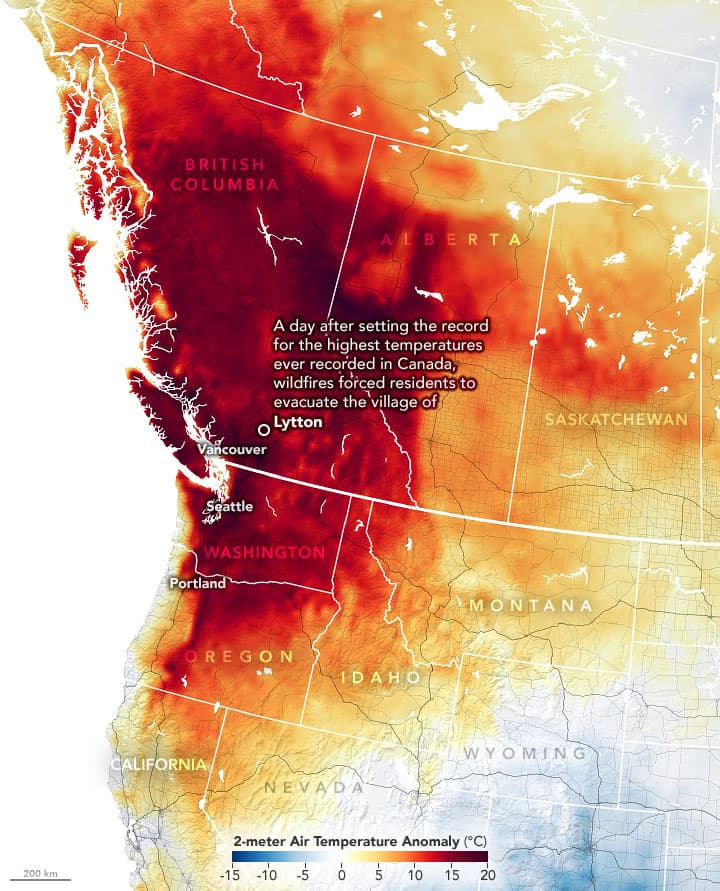

All of this played out during an unusually severe and odds-defying heat wave that pushed temperatures in British Colombia to record levels. Those extremes temperatures would have been “virtually impossible” without global warming, according to scientists from the World Weather Attribution initiative.

“We’re seeing pyroCbs occur almost nightly now, and we’re only halfway through the fire season. This could get much worse before it gets better.”

– David Peterson

With extreme fires and pyroCbs becoming more common, Fromm and Peterson find themselves asking what it all means. “We are running projects to make it easier to forecast where pyroCbs are going to pop up. The hope is that we can improve the systems that keep firefighters, pilots, and people as safe as possible,” said Peterson. “But we’re also watching how much smoke reaches the stratosphere and developing methods to quantify what it means for Earth’s radiative balance and climate.”

Based on past events—including a “super outbreak” in December 2019 and January 2020 when pyroCbs were even more numerous—scientists know that the smoke these events inject into the stratosphere can spread out and behave like a massive shade, leading to temporary regional cooling. The Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) image above shows several pyroCbs rising from smoke plumes that were part of that outbreak.

With enough smoke in the stratosphere, the cooling effect could be sizable, perhaps even enough to cause global temperatures to decline, much like the eruption of ash from Mount Pinatubo famously did in the 1990s due to the volcanic particles that lingered in the atmosphere. The Australian fires delivered about 1/10th the mass of cooling aerosols into the stratosphere than Pinatubo did. “If pyrocbs become more frequent, the climate impacts could really start to add up,” said Fromm. “It’s something we will be watching closely.”

NASA Earth Observatory images by Joshua Stevens and Lauren Dauphin, using MODIS and GOES data from NASA EOSDIS LANCE and GIBS/Worldview, Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey, and GEOS-5 data from the Global Modeling and Assimilation Office at NASA GSFC.

Great article! Please keep them coming. The cooling effect is interesting. If you look at the gradual rise of average global temperature over the years, there is a notch in 1983 due to the Mt. St. Helens release. That became a big ski year in the East, and also was deemed to be a lesser wine-making year in California due to the cooler weather. When Pinatubo released in June, 1991, because of the experience with Mt. St. Helens, I got my boards ready for a great following ski season in New England (seriously). And sure enough, it was a snowy ski season. And, for cycling, the summer was noticeably cooler that year.

The noted climatologist Reid Bryson wrote a popular book in the ‘70’s called “The Cooling” which projected that the large amount of particulate matter that the world is injecting into its atmosphere would *reduce* the average global temperature; it minimized the effect from the CO2 that we are putting into the air. According to this SnowBrains article, we’re seeing some of the Bryson effect with these smoke storms.

But I think it’s better to control global warming than dump all that smoke into the atmosphere to get our global temperatures back to normal. Until then, we’ll have to take advantage of this smoke to get more snow on the Eastern mountain ranges.