A skier caught in an avalanche in Millcreek Canyon located near Salt Lake City, Utah, survived by clinging to a tree. Once the slide had subsided, the skier managed to locate another member of his group, and the two of them began using their avalanche beacons to rescue others buried beneath the snow. Two separate groups were caught in the avalanche, including one group of five, and another group of three. Six skiers were buried, and the two who were not buried managed to rescue two others. The two who were rescued were buried beneath 3-5 feet of snow, making this rescue especially impressive. The other four, consisting of two men and two women in their twenties, were not as fortunate and passed away in the snow.

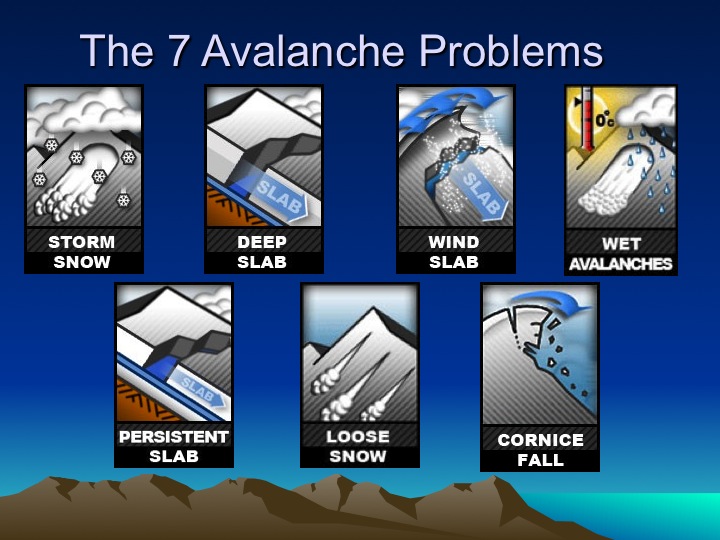

Both groups were ascending when the avalanche occurred. One of them reported hearing “the thunderclap of a collapse”, and looked up to see a wall of white coming towards them. According to the Utah Avalanche Center, the avalanche was classified as a hard slab avalanche and was approximately 1,000 feet across and 3.5 feet deep. The avalanche slid about 400 vertical feet before coming to a stop. Hard slab avalanches occur when there is a harder denser layer atop a weaker layer. In this case, the weaker layer was made up of facets. Facets are basically tiny little ice pieces that do not clump together. This allows the top layer to easily slide on top of them, causing an avalanche.

It is unclear at this time how the avalanche was triggered. However, the fact that it occurred while the groups were ascending made this avalanche particularly deadly. Experienced backcountry skiers know the importance of keeping space between each other in case of an avalanche. However, this practice isn’t followed as strictly by many skiers while ascending, because most avalanches are triggered during the descent. Significant avalanche risks still do exist while ascending, and proper spacing should be maintained at all times while in the backcountry. Since the two groups were ascending when the avalanche occurred, they were likely in a close single file line going up a skin track, making the avalanche particularly devastating.

Both groups had experience in the backcountry and had done their research before going out. They knew the avalanche danger was high, which is why they stuck to a slightly less steep face. According to avalanche.org, most avalanches occur between 35-50 degrees, and the slope that they were skiing on was 30 degrees. While this angle is definitely a risky angle to be skiing, it is still usually considered to be safer. In addition, one of the groups had already skied the face earlier that morning, further adding to the illusion that it was “safe”.

Why has this season been so deadly? So far this winter, 21 people have lost their lives to avalanches in the United States. According to the Colorado Avalanche Information Center, on average, 25 people in the United States die in avalanches per year. With the winter just a little more than halfway over, this season is on track to being one of the deadliest winters on record.

This season has been particularly deadly in part due to COVID-19 encouraging inexperienced people to head into the backcountry to avoid crowded ski resorts. However, the main reason that avalanches have been so devastating this year is because of the instability of the snowpack. Many places, including Colorado and Utah, experienced a shallow early season snowpack, followed by a series of large storms. These large storms are sitting atop a persistent weak layer that is just waiting to break free. In addition, this season has been particularly windy due to it being a La Niña season, further contributing to increased wind loading and snowpack instability.

Second statistic in my last comment is reversed, its 35% uphill, 65% downhill

Hi Grant, thank you for your comment, and for the relevant study you attached. I apologize if I was misleading at all in my article, and have updated it to make it a bit more clear. I fully agree with you that proper spacing should be followed at all times when in the backcountry. However, I’m sure that you can agree that this practice isn’t always followed by many when ascending. I’m hoping that this article will shed some light on the idea that you can never let your guard down when you are out there.

“However, this practice isn’t followed as strictly while ascending, because most avalanches are triggered during the descent.” This is wrong and kills people. You should ALWAYS be spread out in avalanche terrain. In groups, avalanches are triggered while going uphill 50% of the time, downhill 50% of the time. This is different when you have a solo traveler (65% vs 35%). You’re perpetrating a myth here, that these tourers likely believed and may have led to their death. Study here, page 155, https://www.wsl.ch/fileadmin/user_upload/WSL/Mitarbeitende/schweizj/Schweizer_Luetschg_Skier_avalanches_CRST_2001.pdf

You paraphrased his article. Most avalanches do happen during the descent. Internet warriors are the worst, guess I’m one of them now.

#Troll