In this week’s edition of Origins, we will take a look into the history of how avalanches have been avoided in and out of ski resorts. If you missed last week’s Origins on the Freeride World Tour you can check it out here:

- Related: Origins: Freeride World Tour

Avalanches are extremely dangerous and fatal events. Avoiding them at all costs is crucial not only for ski resorts but also for mountain towns that can be right in their path. In 2019, 25 people died due to avalanches in the US alone. While this article will not go in-depth on the causes of avalanches, if you are going into the backcountry make sure you are educated, know the forecast, and have a plan. Be in the know, have the gear, and ski with a friend!

This article will mainly focus on the history of US avalanche control. There is enough information regarding just the U.S. that you could write an entire novel on. So be prepared, this will be a long one. For you nerds out there (like me) the more information the more interesting.

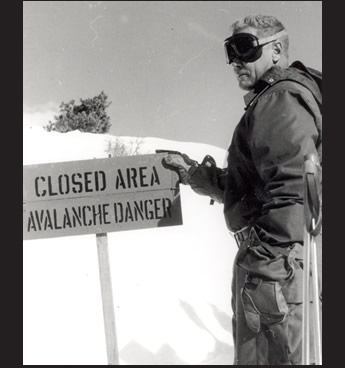

Our story begins in a little place called Alta, Utah. This town and now resort nestled along SR 210 in the Little Cottonwood Canyon (LCC) is the birthplace of avalanche research, forecasting, and control in North America. It was here in 1939, that the first Snow Rangers were hired by the U.S. Forest Service. The first ranger hired was Douglass Wadsworth and was directed to mitigate the danger of avalanches in the canyon. This was the first program in North America devoted to the study and control of avalanches. The location was no coincidence as Little Cottonwood Canyon has abundant snowfall and steep faces, leading to extremely high avalanche danger in most seasons. It was also the site of the first ski resort on national forest land, Alta, which was given a permit to operate in 1938. The new resort only further stressed the importance of avalanche mitigation in the canyon. Following the conclusion of WWII, the forest service hired Monty Atwater, now known as the grandfather of U.S. avalanche forecasting and mitigation, as a Snow Ranger in LCC.

Monty Atwater, a former member of the 10th Mountain Division, conducted research on snow-safety in LCC and quickly became a world-renowned name in avalanche control. His work was crucial for understanding avalanche paths and for using military weapons to mitigate avalanche risk. During his time spent in WWII, Atwater noticed the use of military explosives and guns to trigger avalanches. Due to this knowledge, Monty quickly began working with explosives as a key trigger for avalanches.

Some of Atwater’s early techniques involved drilling holes in cornices to place explosives, lowering explosives in a coffee can to a slope (yea this was a real technique), and hanging explosives from tree branches to create an air blast onto the snowpack. He gave up on the air blast technique after one try, but a similar technique would later be created to trigger avalanches. Atwater contacted the Utah National Guard in 1949 and arranged for 15 rounds of a 75 mm French Howitzer to be fired into slopes above Alta. This was the first use of artillery for avalanche control in the United States.

After seeing positive results from the Howitzer test, the Forest Service decided to permanently station military artillery at Alta for avalanche mitigation. Only Army national guard troops could fire the weapon, which caused some issues for Atwater. On storm days the personnel for the gun, located in Salt Lake City, could not always get up to fire it. This frustrated Atwater, who could not legally fire the gun, seeing the danger being created above him. He eventually fired the gun on multiple occasions without authorization (this guy was a legend) and his manager later threatened to discipline him. The rules were later changed so Snow Rangers could operate the gun legally. The success of these guns allowed for the inclusion of recoilless artillery that was later implemented at 20 different ski resorts. It was at this same time that states began using military artillery to mitigate avalanches threatening major mountain highways.

Atwater was smart. He knew that artillery ordinances were a limited resource and eventually might not be available for avalanche mitigation. In the 1950s, he began perfecting the use of handheld explosives that could supplement the use of artillery, but also for an alternative for the large guns. It was this research that led to the first Avalauncher.

This new invention, designed after pitching machines, used pressurized nitrogen to shoot 1-kilogram explosives up to a few hundred meters away. While this new weapon against avalanches provided an alternative to artillery, it did not have the same accuracy, range, or explosive size capabilities as the bigger military machines. The fact is no one has yet come up with an invention that can rival the larger artillery, but the Avalauncher provided a needed at least one alternative course of mitigation.

It only took a matter of time before the 75mm and 105mm howitzers ran out of ammunition. The US military, the only source of munitions for the weapons ran out of supply in the early 1990s and the Avalanche Artillery Users of North America Committee (AAUNAC) looked for new weapons. They decided to turn toward the 106 mm recoilless rifle system (106mm RR). As weird as it sounds, Washington chose to use tanks stationed at Steven’s Pass instead of the 106 mm gun. These new guns worked well until 1995 when an explosion turned deadly at Alpine Meadows, California. An in-bore explosion (explosion within the gun itself) ended up killing one of the Forest Service gunners. It was later deemed that a manufacturing defect in the ordinance was to blame for the tragic incident. After the explosion event, some operators chose to switch to the 105 Howitzers, and all others were required to build up barriers for the 106mm to fire behind.

Above is a great video showing off the M60 tanks used on Stevens Pass. Credit: Stevens Pass Mountain Resort

Sadly, two more in-bore explosions from 106mm RR happened at Mammoth Mountain in December 2002. Thankfully, due to protective barriers, no one was injured from the explosions. While the Forest Service decided to end the use of the weapon afterward, they would have to be used that winter as changing weapons during mid-winter would be a difficult task. In 2003, all remaining 106mm RR’s were replaced by 105 Howitzers.

While the howitzers were a good weapon for avalanche control, everyone knew they were not the permanent answer. There was only roughly 10-15 years supply of munitions left when they were put into full service. Alternatives to these guns would have to be found. Many alternatives were proposed such as the LOCAT gas-powered Avalauncher, Gaz-ex Exploder, and Wyssen Towers. While deemed as viable options, for many the artillery system was the only way to get the distance and firepower needed to mitigate multiple slopes efficiently and cost-effectively.

Alternatives to giant artillery slowly gained tranction across the United States. Loveland Pass in Colorado received 16 Gazex exploders in 2016. This remote-controlled, gas-powered, system triggers concussive air blasts to the snowpack. Gazex systems are used in a lot of resorts including Squaw Valley, Taos, and Crystal Mountain among others. These systems have some immense upsides as they mitigate personnel danger due to their ability to be detonated remotely. It will be interesting to see how these systems get adopted in the coming future and if they will take over the traditional artillery approach.

The history of U.S. avalanche control is long and detailed. If you made it to this point you are probably a nerd just like me. Thanks for reading the entire article. I had a great time researching and learning about the progression of avalanche control in the United States. Next week we will dig deep into the history of snowboarding!

I made a table lamp out of a 105mm shell casing. looks cool at the cabin