In this week’s edition of Origins, we take a look at the humble beginning of snow surveying within the Sierra Nevada Mountains. If you missed last week’s edition on how the New Deal helped promote the U.S. ski industry you can check it out here:

- Related: Origins: How The New Deal Helped Foster The U.S. Ski Industry

California’s most precious natural resource is the Sierra Nevada snowpack. Although snow enthusiasts would beg to differ, the snow’s value doesn’t come from recreational activities and tourism, but from what happens when it melts. As has been recently highlighted, California is susceptible to extreme droughts. Water can be scarce in the summertime especially when there is little to no rain falling within the state’s boundaries apart from winter. A healthy snowpack allows the state to access a continuous flow of freshwater throughout the year. Slow melts on large snowpacks are the most ideal situation for California. This gives water controllers more time to adjust water flowing from the mountains down to the inland valleys. The Central Sierra Snow Lab was created to help understand and monitor the Sierra Nevada snowpack. Let’s take a look at when it was founded and what the laboratory actually does.

Our story begins in 1892 when Dr. James Church, a Michigan native, moved to Reno. Dr. Church moved to Nevada to teach at the University of Nevada in Reno, but he became well known for his work in snow surveying during the early 20th century. In 1905, he established the first Sierra weather outpost on the summit of Mt. Rose(10,776 ft). It sits next to the Mt. Rose ski area that resides on Slide Mountain (shown below).

Dr. Church developed methods for measuring snow depth and snow-water equivalent (Amount of water within a snowpack). His research helped him discover that snow depth does not always indicate the amount of water within it. To measure water equivalent in the snow, he designed the Mt. Rose Snow Sampler; a hollow metal tube that could be thrust into the snowpack to extract a snow core. Once the core was extracted it could be analyzed for water content by using a portable scale. This simple yet effective device is still in use to this day.

In 1911, Church used the system to predict the rise of Lake Tahoe from the melting snowpack. This data was extremely useful for water management in the basin to avoid unnecessary flooding. The predictions also helped accurately predict the flow of water moving down the Truckee river into Reno, the city’s most important source of freshwater. His research led him to be dubbed the “Father of Snow Surveying”. While Dr. Church played a crucial part in the study of snowpacks, he lacked the equipment and training to delve deeper into the science.

The next major breakthrough came in 1945 when U.S. Weather Bureau physicist Dr. Robert Gerdel was directed to establish the Central Sierra Snow Laboratory at Soda Springs near Donner Pass. The U.S. government had just begun to recognize the importance of water management out west and this was one of the first steps to better understand the Sierra Nevada snowpack. Dr. Gerdel was chosen to run the technical aspects of the project due to his expertise and training. The goal of the lab was to study the hydrodynamics of snowmelt and its relationship to runoff to create better flood control structures and more accurate predictions of stream and river flow during the spring.

Gerdel was responsible for locating sites and building 3 snow laboratories within the western mountains of the United States. Soda Springs was chosen for the California lab and the others were built in Oregon and Montana. The Soda Spring site was chosen due to the site’s high amount of both snow and rain during the winter. Once the two-story building was completed and fitted with its new scientific instruments it was staffed with Gerdel, a hydrologic engineer, a meteorologist, and an engineering aid. The site used Dr. Church’s Snow Sampler to obtain snow cores, in addition to analyzing solar radiation, air/soil/snow temperatures, and wind velocities.

Among the various technological innovations created by the snow lab, one of the most important was the first-ever nuclear snow gauge (1948). This instrument used a small amount of radioactive Cobalt 60 to bounce gamma rays off the snow. The way these rays and their energy equivalent interacted with the snow gave an indication of the water content inside. Equipped with a radio transmitter, the signal could be relayed in real-time to both the lab and to other agencies in Sacramento and San Francisco. Remote technology was a massive breakthrough for snow surveying. It allowed the team to monitor vast areas of the mountains that prior to this breakthrough, would have required teams to physically visit in order to study. The device also allowed researchers to get more accurate data than manual methods. Previously, scientists would have had to walk around an area to find a good site to measure the snow, often disrupting the snowpack underneath and increasing the chance for error, and physically extract the samples themselves.

In the 1960s, the use of these remote technologies began to grow exponentially across the Sierra Nevada Range. Pressure Pillows, also known as snow pillows, were installed in various locations in the mountains. Snow pillows consisted of a vinyl bladder filled with a mixture of alcohol and water that were placed on the ground and protected from animals. During the winter, the bladder would measure the weight of snow on top of it and relay information remotely to the snow laboratory.

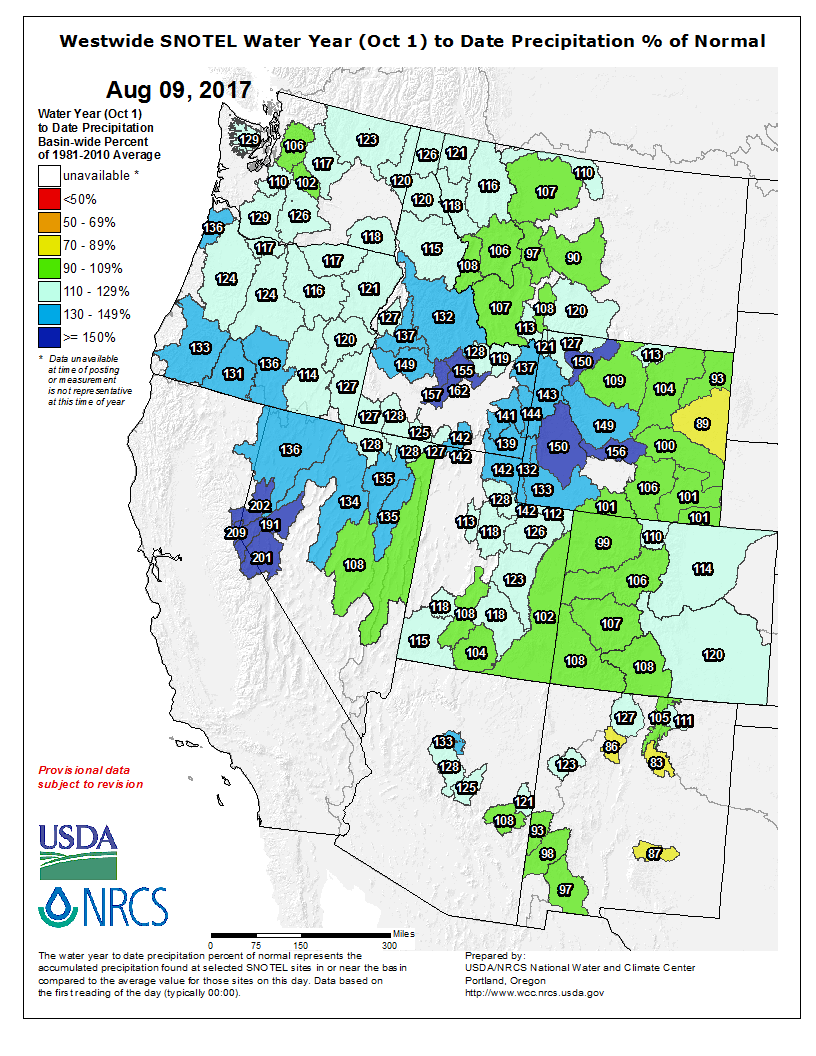

The system developed to relay data from the snow pillows to the main laboratory is now called SNOTEL (Snowpack Telemetry). The system relays radio signals by bouncing them off ionized gas trails of meteor dust in the upper atmosphere. This revolutionized the data collection process and allowed for over 600 SNOTEL sites to be established throughout the west.

In the 1990s the Central Sierra Snow Laboratory began to retire the snow pillows in favor of a new technology, gamma-ray detectors. Designed by Sandia National Laboratories in Livermore Calfornia, the gamma-ray detectors were more reliable and accurate than the snow pillows. The latest technology implemented after the gamma-ray detectors were satellite technology. While these technologies are making it easier to get a picture of the overall snowpack, manual measuring techniques will not be going away anytime soon. They provide a way for scientists to gauge the accuracy of their remote equipment or gain more information from specific sites not included in SNOTEL.

In the late 1990s budget cuts forced the snow laboratory to close. Luckily, the University of California came to the rescue and funded the station. Today the lab continues to provide crucial water management data to the state of California and Nevada. These laboratories are crucial not only for a better understanding of how snow affects water resources in the west, but also a way to track how a changing climate is affecting snowfall in the region.

The Mount Rose Ski Area isn’t on the actual Mount Rose. The ski Area is on Slide Mountain which sits several miles to the south of the Mt Rose Summit. So the picture labeled Mt. Rose & Lake Tahoe is actually Slide Mountain or The Mt Rose Ski Area & Lake Tahoe. Remember, Mt Rose isn’t in the Sierra’s, it’s part of the Carson Range.

Hi, Thanks for the catch there. Writing these up can lead to silly mistakes like this sometimes. It’s been updated!

Nice read Ryan! A good history lesson we see year in CA on the news when they do the snow ,survey of the Sierras. It fires me up for skiing!

Dad