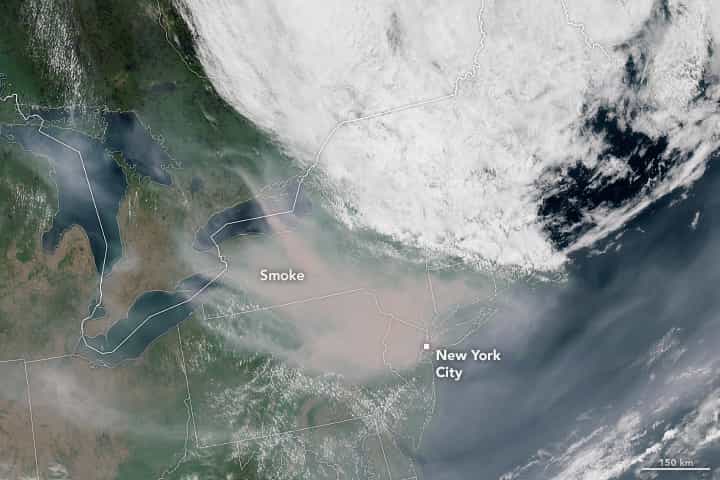

Wildfire smoke from Canada has passed over the northeastern U.S. multiple times each summer in recent years, but it often goes unnoticed because it is relatively high in the atmosphere. That was not the case in June 2023. In the first week of the month, large amounts of smoke from fires in Quebec poured south into the eastern U.S. and degraded the quality of surface-level air that tens of millions of people breathe.

Winds typically move smoke from fires in Quebec toward the east and out to sea. But in June 2023, a persistent coastal low centered near Prince Edward Island instead steered smoke south into the United States. This image, from the Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellite 16 (GOES-16), shows smoke sweeping into New York and Pennsylvania on the morning of June 7, 2023. GOES-16 is operated by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA); NASA helps develop and launch the GOES series of satellites.

Smoke reaching the northeastern United States from Canada in 2023 from fires raging in western Canada has mostly arrived at fairly high altitudes. But since the fires in Quebec are relatively close to the northeast U.S., a much larger proportion of the smoke arrived in surface-level air. Around the time of the image, AirNow air quality monitors measured levels of fine particulate matter (PM2.5) soaring above 400 micrograms per cubic meter of air in Syracuse, New York—the highest on record for the city since routine measurements began in 1999.

“The surface smoke pollution from New York to the D.C. region is easily the most significant since at least July 2002, when a similar situation occurred with nearby fires in Quebec,” said Ryan Stauffer, an atmospheric scientist based at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center. “This event is rivaling, and in some cases will likely surpass the observed 2002 smoke pollution.”

According to Stauffer, the air quality index for PM2.5 in New York City surpassed 175 (code red) on June 6, topping the previous record of 167 from 2002. The next day, on June 7, 2023, “the D.C. region joined New York City and experienced some of its most smoke-polluted air in the past 25 years,” Stauffer said.

Several NASA satellites are collecting data throughout the event. For example, the Terra, Aqua, and Aura satellites observe how smoke particles affect how much light the atmosphere absorbs and reflects (aerosol optical depth), while the Cloud-Aerosol Lidar and Infrared Pathfinder Satellite Observation (CALIPSO) mission collects observations of smoke height. Meanwhile, data from NASA’s ground-based Micro-Pulse Lidar Network(MPLNET) and Aerosol Robotic Network (AERONET) indicate that a significant amount of smoke is present near the surface.

Such thick smoke at ground level is rare in the eastern U.S., prompting many people to notice the optical effects smoke can have on sunlight. “Smoke particles scatter and absorb shorter wavelengths of sunlight like blues, greens, and yellows more easily compared to the longer-wavelength oranges and reds, so we see muted red sunrises and sunsets under heavy smoke conditions,” explained Stauffer. “In extreme cases like this week, the Sun may become obscured entirely.”

The photograph above shows smoke reddening the morning Sun and turning skies gray over NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center on June 7, 2023. It was taken by Colin Seftor, an atmospheric scientist based at the center. At the time of the photograph, MPLNET datashow a multi-layered smoke plume overhead, with thick smoke near the surface up to about 3 kilometers (2 miles), followed by a thinner layer at about 6 kilometers, and a faint layer of smoke hovering at about 12 kilometers.

“There are different histories to each one of those layers that would be interesting to untangle,” said Michael Fromm, an atmospheric scientist at the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory, after seeing the MPLNET data. “The layer lurking at 12 kilometers is a month old and can actually be traced back to intense fires in Alberta on May 5.”

This post first appeared on NASA Earth Observatory. NASA Earth Observatory image by Lauren Dauphin, using GOES 16 imagery courtesy of NOAA and the National Environmental Satellite, Data, and Information Service (NESDIS). Photograph by Colin Seftor (NASA/SSAI). Story by Adam Voiland.