Alaska’s Mount Spurr—a 11,070-ft glacier-clad volcano 75 miles west of Anchorage—is showing worrisome signs of life. The Alaska Volcano Observatory (AVO) reports elevated seismic activity with numerous small, shallow earthquakes now detected daily beneath the mountain. Over the past month, more than 100 quakes per week have been recorded, some up to magnitude 2.7, totaling thousands of tremors since last year. Instruments on the volcano also indicate it is swelling subtly; the ground has bulged about 6–7 cm (2.5 inches) outward so far—a sign that magma is pushing up below. During recent overflights, scientists observed vigorous gas venting at Spurr’s summit and its Crater Peak vent, with sulfur dioxide emissions spiking to ~450 tons per day (up from <50 tons late last year). These clues—more quakes, ground deformation, and increased volcanic gases—all point to magma intruding beneath Mount Spurr.

Eruption Outlook: “50/50 Chance” in Coming Weeks

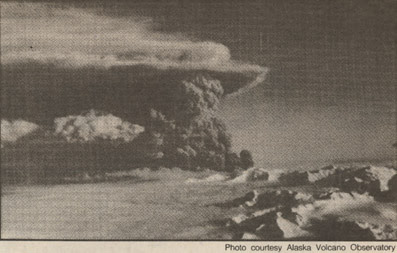

Volcanologists are now carefully eyeing Mount Spurr for a potential eruption. AVO has raised the official Volcano Alert Level to Advisory and the Aviation Color Code to Yellow. In a special information statement, the USGS noted that fresh magma beneath Spurr makes an eruption “likely, but not certain, to occur within the next few weeks to months.” Matthew Haney, AVO’s Scientist-in-Charge, put the odds around 50-50 at present. The most probable scenario, if an eruption does happen, is an explosive burst similar to Spurr’s 1953 and 1992 events. “Those eruptions each lasted a few hours and produced ash clouds carried downwind for hundreds of miles,” AVO wrote, with minor ashfall (up to about ¼ inch) on some Alaskan communities. On the volcano’s slopes, any blast could trigger hot pyroclastic flows and mudflows (lahars) around the summit, though these would likely stay confined to uninhabited valleys and pose no direct threat to communities.

Encouragingly, scientists stress that warning signs should precede any eruption. “Based on previous eruptions, changes from current activity in the earthquakes, ground deformation, summit lake, and fumaroles would be expected if magma began to move closer to the surface,” the USGS notes—meaning an eruption would likely be heralded by even stronger unrest. These precursors might include swarms of larger quakes, continuous seismic tremor, rapid ground uplift, or sudden melting of summit snow and ice. In the 1992 episode, such telltale changes kicked in about three weeks before the first explosion. AVO officials say they will swiftly escalate alerts to Watch/Warning (Orange or Red) if data suggest an eruption is imminent within days or hours. For now, they are not calling for evacuations or drastic measures, especially since past unrest in 2004–2006 (and a blip in 2012) did not lead to an eruption. This could yet be a “failed eruption” where magma stalls underground—a scenario AVO considers possible if the unrest plateaus.

Ashfall Risks and Air Travel Hazards

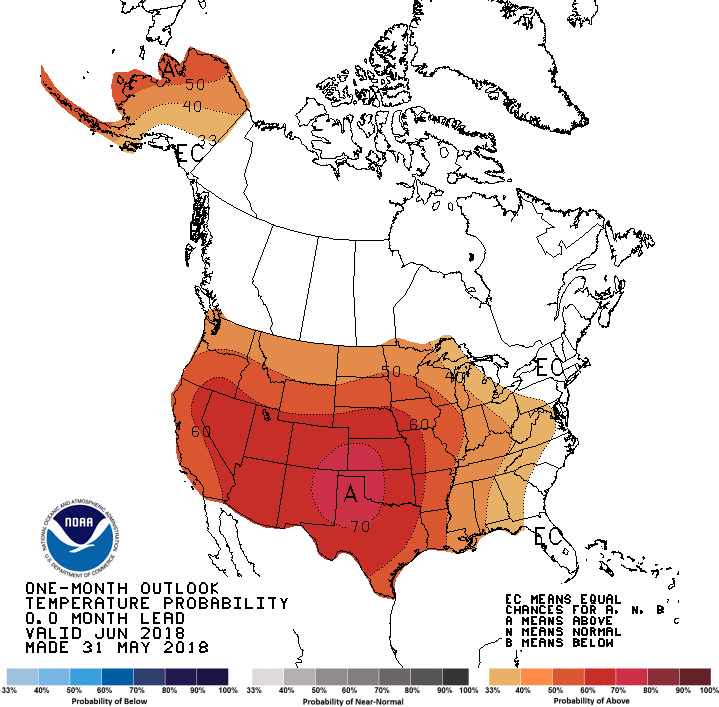

If Mount Spurr does erupt, volcanic ash will be the main hazard for Alaskans. Anchorage, the state’s largest city, lies just east of the volcano and could be cloaked in a gritty dusting of ash, depending on wind direction. In the likely case of a moderate eruption, scientists expect only light ashfall (a few millimeters) in parts of south-central Alaska. That’s enough to coat cars and roads, contaminate drinking water, and pose respiratory irritations, but not bury buildings. However, even a thin ash layer can wreak havoc on daily life and infrastructure. During Spurr’s last eruptions in 1992, fine ash blew into Anchorage, forcing Ted Stevens International Airport to shut down for ~20 hours. Air traffic was disrupted as jet engines cannot safely operate in an ash cloud. Millions of dollars were spent cleaning up ash in the city, and while the eruption itself caused no direct fatalities, one resident suffered a fatal heart attack while shoveling ash off their roof. Today, officials are prepared to issue ashfall advisories and reroute flights if needed—the National Weather Service and FAA continuously monitor volcanic ash for aviation safety. Spurr’s current Yellow alert has already put pilots on notice. If an eruption sends ash skyward, forecasters warn that flight paths over Alaska and the busy Great Circle routes to Asia could be diverted to avoid the abrasive, engine-clogging ash particles.

Local Impacts and Historical Context

Communities closest to Mount Spurr are small (the nearest, Beluga and Tyonek, lie ~60 km away), but Anchorage and the Mat-Su valley house over half the state’s population within 130 km (80 miles) of the volcano. Thankfully, Spurr has no history of giant cataclysms—the likely eruptions would be moderate and short-lived. The worst-case of a massive eruption (thick ash deposits and major regional impacts) is considered very low probability. More typically, Mount Spurr’s eruptions have been on the scale of the 1953 and 1992 events: dramatic but manageable. The 1953 eruption sent an ash plume over 10 km high and dusted Anchorage in gray powder, yet no lives were lost. In 1992, Spurr’s Crater Peak vent erupted three times (June, August, and September), each time belching ash that drifted over Anchorage. Residents wore dust masks and shoveled ash as if it were dirty snow. Aside from the one heart attack fatality and a few minor accidents, there were no direct deaths. These past events show that while Mount Spurr can disrupt daily life, Alaska has endured its tantrums before.

Geologists and emergency officials are on high alert now, tracking every tremor at Spurr. The Alaska Volcano Observatory has a dense web of seismic stations, satellites, gas sensors, and webcams trained on the peak 24/7. Updates are being issued daily to inform Alaskans of any changes. For the moment, Spurr’s status remains at Advisory/Yellow, and no eruption is imminent. But that could change with little notice. As AVO reminds, an explosive eruption could even occur “with little or no additional warning”, which would be extremely hazardous to anyone nearby or flying overhead. The prudent approach is continued vigilance. If magma indeed makes a break for the surface, scientists are optimistic that early warning signals will give communities and aviators time to prepare. With a watchful eye on Mount Spurr, Alaskans are keeping ash masks handy—just in case the rumbling volcano decides it’s time for an encore.