The Idaho Supreme Court recently overturned the dismissal of a lawsuit brought against Sun Valley Resort, Idaho, for negligence in the death of 65-year-old Stewart ‘Stu’ Milus, who died in 2019 after colliding with a snowgun on Lower River Run. The Court’s ruling sends the lawsuit to trial, where a jury will decide whether or not Sun Valley was responsible for Milus’ death.

The case revolves around two main questions. First, was the yellow padding that Sun Valley had placed on the snow gun a sufficient warning marker of the hazard the snow gun posed? And second, did Sun Valley have to provide more signage than was in place to indicate the presence of snowmaking equipment on the run? The Court’s ruling states that a jury trial is needed to decide the facts of the case.

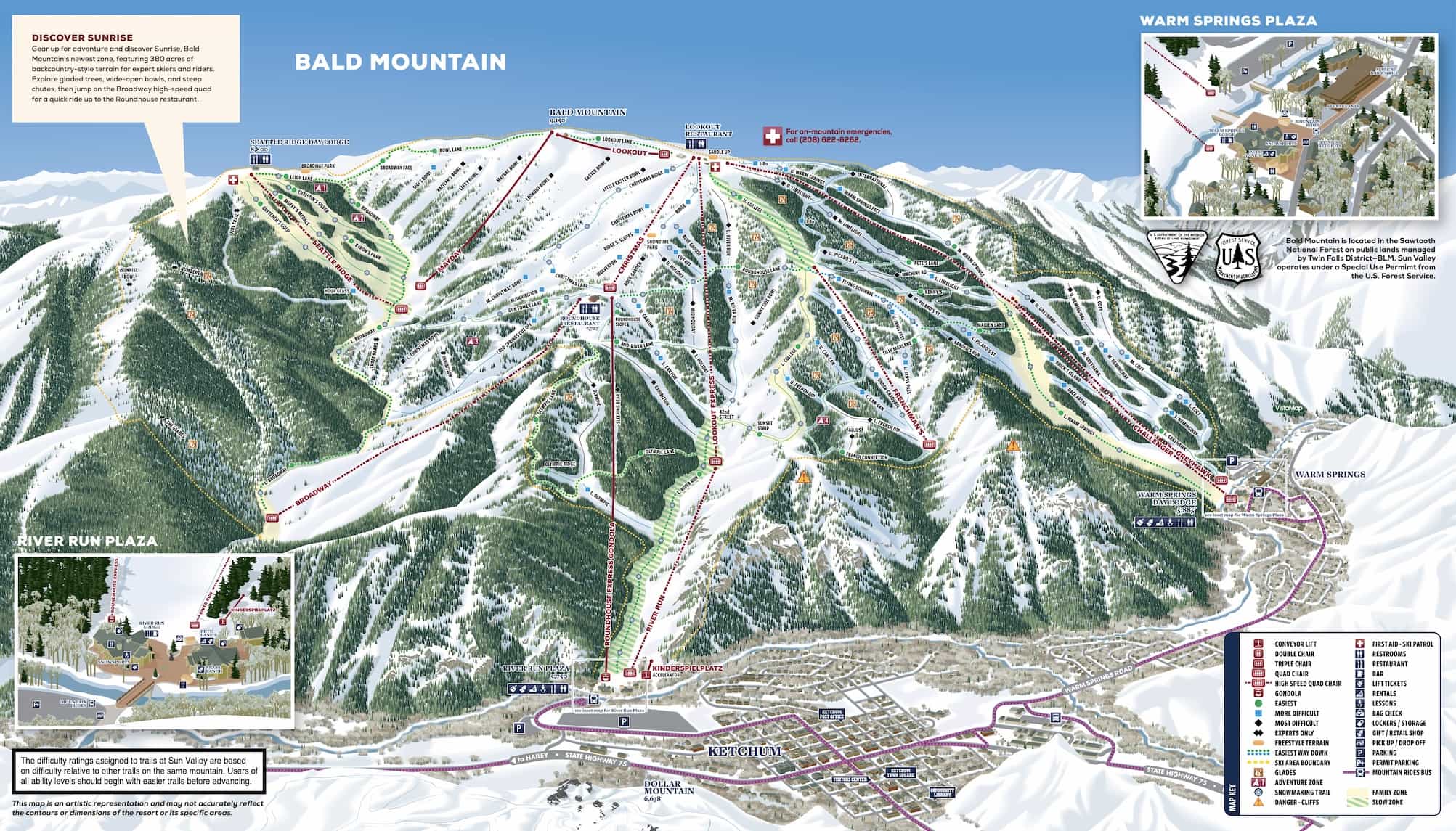

On November 30th, 2019, Stu Milus was skiing down Lower River Run, a beginner trail at Sun Valley, when he collided with a snow gun placed in the middle of the run. An off-duty doctor started CPR, and ski patrol transported him off the mountain soon after that. Milus was pronounced dead later that day. The snow gun that Milus collided with had a yellow pad on it, and there was a sign placed near the top of the River Run Chairlift that said “Caution Snowmaking In Progress,” but the snowgun was not actively blowing snow. Milus was reportedly a beginner skier who had been skiing slowly all morning.

Stu Milus’ wife, Laura Milus, and his eight-year-old son filed a lawsuit against Sun Valley in 2021 for negligence in the death of Stu Milus. The lawsuit alleged that the snowgun was not sufficiently marked with a ‘warning implement’ and that the sign indicating snowmaking operations were in progress was not properly placed near the top of the ski run. The lawsuit was dismissed with prejudice in March 2022, with a summary judgment that said Sun Valley had followed the Idaho Ski Statutes and was, therefore, not liable for Milus’ death. Laura Milus appealed the ruling to the Idaho Supreme Court in July 2022, and the Court overturned the district court ruling in December 2023. The case will be decided by a jury in a trial that has reportedly not been scheduled yet.

Skiers and ski areas in Idaho are regulated by Idaho Code 6-1101 – 6-1109, commonly referred to as the Idaho Ski Statutes. The law includes ten specific responsibilities for ski areas, including the marking of trail difficulty and trail closures and the presence of a ski patrol. Typically, if ski areas prove they have fulfilled all ten duties, then they cannot be held responsible for injuries sustained by guests using the ski area. The law specifically states that “each skier expressly assumes the risk of and legal responsibility for any injury to person or property that results from participation in the sport of skiing including… snowmaking and snow grooming equipment which is plainly visible or marked.” The district court dismissed the initial lawsuit because it agreed with Sun Valley’s assertion that Sun Valley had accomplished all ten responsibilities, specifically that the snowgun in question was plainly visible or marked. The Supreme Court sided with Laura Milus, saying that a yellow pad may not necessarily count as the warning implementation the law requires and that a jury must decide the facts of the case.

A jury verdict that favors Laura Milus would represent a significant shift in the interpretation of the Idaho Ski Statutes and, with it, a significant change in ski area policy and risk management. As has been highlighted in both the summary judgment and Supreme Court decision, the law does not specify what an adequate warning implementation is. Snowguns and other hazards currently are routinely marked at most ski areas in the United States with either a sign, a pad, or some netting. Pads and netting are more frequently used because they may also be able to reduce the risk of that particular hazard. However, the Idaho Ski Statute states that ski areas “shall have no duty to eliminate, alter, control or lessen the risks inherent in the sport of skiing.” One interpretation of this part of the law is that a sign that says “Warning: Snowgun” would be sufficient with no additional padding or netting. If a jury rules that padding is not an adequate marker of a hazard, an extreme case could be imagined where ski resort guests are confronted with dozens of signs on a single run marking the dangers of snowguns, light poles, lift towers, and other ski area equipment. Some Idaho ski areas have already added additional marking to snowmaking equipment, because of anxiety over possible increased liability.

The Supreme Court ruling does not assert whether the Milus’ or Sun Valley’s interpretation of the law is correct. Lawyers for the Milus family and for Sun Valley will have to prove to a jury whether or not Sun Valley followed the Idaho Ski Statute and, thus, whether or not they were responsible for the death of Stu Milus. The trial has not yet been scheduled.