Granular, Dip-n-dots, sleet, concrete, pins and needles, and of course, the blower pow. If you’re anything like myself, you’ve likely wondered at one point or another what causes so many different ski conditions, and how can you tell when it’s going to be best.

- Related: The Art & Science of Snowflakes

For the passionate all-mountain skier, it’s no secret that powder is the preferred snow type; likewise, it is also no secret that it can be quite elusive.

In order for the snowfall to be considered powder, two Goldilocks scenarios must be met — the first of which is snow-to-water saturation which correlates with humidity level. To explain this concept to those unfamiliar, if you were to melt ten cubic inches of snow and get 1 cubic inch of water, this would be a saturation ratio of 10:1. According to OpenSnow, the best ratio for saturation is approximately 20:1, though TheSkiGirl says anywhere from 20:1 – 30:1 is the best. This makes sense when put into practice, as the higher the ratio, the more snow you get per storm with finite precipitation.

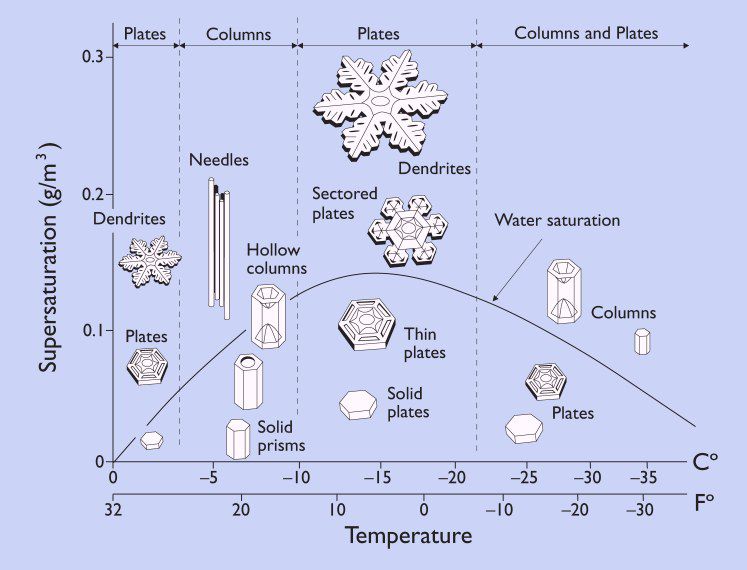

The second of the Goldilocks scenarios is temperature. The flakes that form powder are a specific type of plate snowflake called dendrites — these are the large, pronged, reaching flakes that also are most typically what come to mind when prompted to think of a snowflake. These flakes can occur in temperatures ranging from -5º to 15º Fahrenheit.

When the temperature is just colder than -5º F, the flakes falling from the sky will take a column shape or small plate size, creating icy snow that feels like pins and needles on your cheeks when skiing through it.

And, if it gets to about -10ºF, it could very realistically be too cold to snow. This phenomenon occurs because the colder the air is, the harder it becomes for water to stay in the atmosphere; and since temperature changes gradualy, if it is -10ºF or colder in one location there must be cool temperatures surrounding it. When combined, the result is a wave of precipitation moving in one direction which will inevitably come across a location cold enough to pull snow from the sky before it hits the patch of weather -10ºF or colder. Thus, the snow never reaches the -10ºF patch, and it is determined too cold to snow.

When it’s warmer than 15ºF, a combination of snow shapes occurs that share a common characteristic of low snow-to-water saturation. At the warmer temps, the dendrite shape can still form, but it will be more saturated with water and will compile to create heavy powder conditions often referred to as concrete.

When the snow shape is more column-like in this temperature, the resulting snow is most often the dip-n-dots texture, known as graupel, or sleet. These are some of the least ideal flakes for skiing because as their shape has a minimal surface area to volume ratio, they will compact the tightest when falling on the slope and provide the least snow-bang for your snow-buck.

Finally, the last piece to consider is pressure; the higher you are elevation-wise, the less pressure there is, and therefore the easier it is for water to freeze. This means that temperatures above 32ºF can still make snow, and the snowflake itself can have the ideal, blower dendrite shape even in temperatures closer to 20ºF.

While the graph is standardized for pressure, mountain conditions rarely are. When a low-pressure system rolls through, it is safe to adjust the graph a few degrees warmer to best represent the flake shape, and it is likewise a good idea to prep the fat skis the night before.

In all, the best snow storms for the mountain west will come with high snow-to-water saturation and cool temperatures ranging between 5ºF and 25ºF (when adjusting for considerably low pressure). But if you can’t rely on the weather for a good time, be sure to bring a few friends as insurance.