The first recorded instance of altitude sickness dates back to around 37-32 B.C. A Chinese official named Too Kin referenced the “Big Headache Mountain” while traveling over what is believed to have been the Karakoram Range in the Himalayas [1]. It is no secret that higher elevations have lower levels of oxygen available for the respiration required to sustain life. The effects of higher altitudes on the human body have no doubt been of concern to mankind for as long as we have encountered mountains.

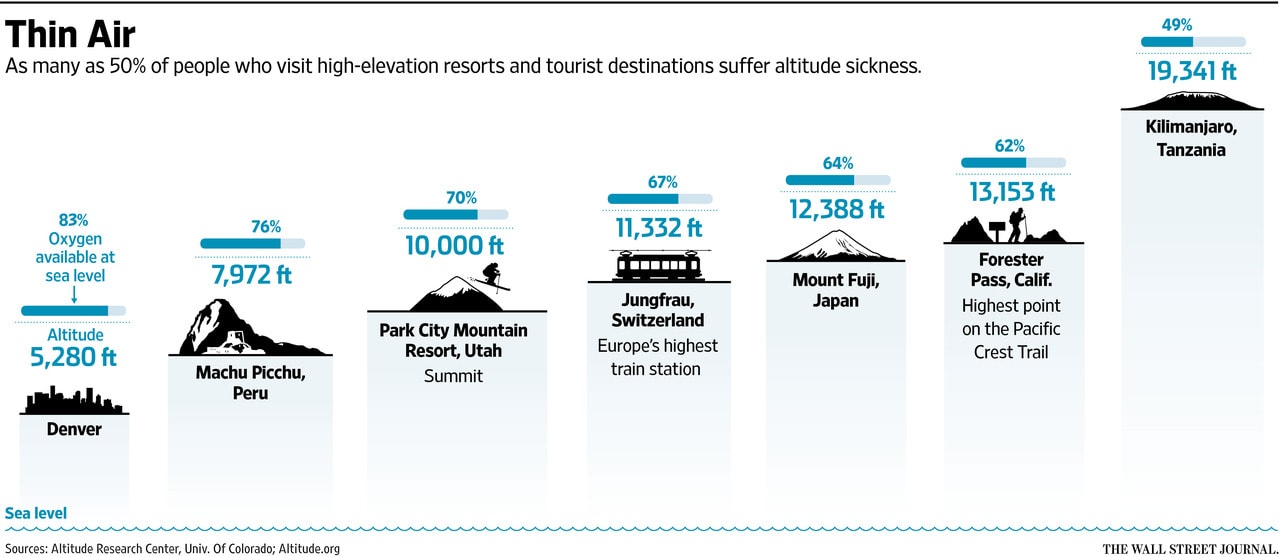

It may not seem terribly surprising to learn that altitude sickness is a concern for individuals trekking through one of the world’s highest mountain ranges. It may, however, surprise you to learn that 20% of those who ascend to just 8,000 ft., and 40% of those who ascend to 10,000ft. will develop symptoms of Acute Mountain Sickness (AMS)[2]. While the symptoms associated with AMS (headache, accompanied by at least one other symptom such as fatigue, gastrointestinal symptoms, or persistent dizziness, all with an onset approximately 6-10hrs. after ascent to altitude) are generally not life-threatening, they should be considered some of the best early warning signs that an individual may be at risk for the further development of a more serious altitude-related illness such as High Altitude Cerebral Edema (HACE) or High Altitude Pulmonary Edema (HAPE).

High Altitude Cerebral Edema (HACE) is rare (occurring in less than 1% of people who ascend to 13,000ft.), but it is life-threatening and should be considered a medical emergency. HACE involves the swelling of the brain as a physiological response to ascent to higher altitudes. According to the Lake Louise Criteria for Altitude Illness, it is marked by a change in mental status or ataxia in individuals already experiencing AMS or a change in mental status and ataxia for individuals with no previous symptoms of AMS. Other less common symptoms may also include deep tendon reflexes, retinal hemorrhages, and blurred vision (among others). HACE is typically fatal within 24 hours if not treated [3][4].

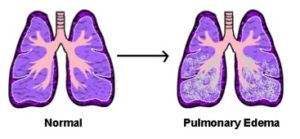

High Altitude Pulmonary Edema (HAPE), however, is much more prevalent than HACE and is considered the #1 Killer at altitude. This is because while it is also a life-threatening condition, its symptoms are frequently mistaken for more benign responses to exercise at altitude and are therefore all too often overlooked or ignored.

Some of the first warning signs that you might have HAPE are decreased exercise performance, shortness of breath while at rest, and a dry cough. All of these symptoms may seem fairly innocuous after a day in the mountains. However, combined with one more of the following signs: rales (bubbling/crackling sounds in your lungs), cyanosis (a bluish tint to skin, lips, and/or nail beds typically associated with low levels of oxygen in the blood), and abnormally high heart or breathing rate, these symptoms confirm that an individual has likely developed HAPE. Left untreated, HAPE has a mortality rate of up to 50% [5][6].

At this time, no reliable methods exist for predicting who may be at higher risk for developing an altitude-related illness. The risk for developing AMS, HAPE, and HACE is best mitigated by ensuring a more gradual ascent that allows the body sufficient time to acclimate to progressively higher elevations. Medical treatment for altitude-related illnesses may vary depending on specific factors. Descent to a lower elevation, however, is ultimately the most critical element of successful treatment for any altitude-related illness, including HAPE. Due to the logistics of mountain travel, this means that time is a factor. Therefore, taking action at the first sign of concern is critically important. It might even save a life.

To learn more, go to Altitude.Org.

Sources:

[1] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0034568783900889

[2] https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/injuries-poisoning/altitude-diseases/altitude-illness

[3] Bärtsch, Peter; Swenson, Erik (2013). “Acute High-Altitude Illnesses”. The New England Journal of Medicine. 368 (24): 2294–302. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp1214870. PMID 23758234.

[4] Schoene, Robert (2008). “Illnesses at High Altitude”. Chest 134 (2): 402–16. doi:10.1378/chest.07-0561.PMID 18682459

[5] https://www.google.com/amp/s/www.climbing.com/.amp/skills/learn-this-understanding-altitude-illness/