Objective hazards in the mountains are comprised of two main categories: environmental factors and human factors. Before heading into the wilderness, a human will make considerations for what to bring in case of an emergency. HAPE is a risk, an almost silent killer which creeps in during situations where rescues are often impossible, like on the side of a mountain. It is caused by prolonged exposure to low oxygen environments. Here’s a question: are you bringing Furosemide in your medkit for an emergency response to HAPE?

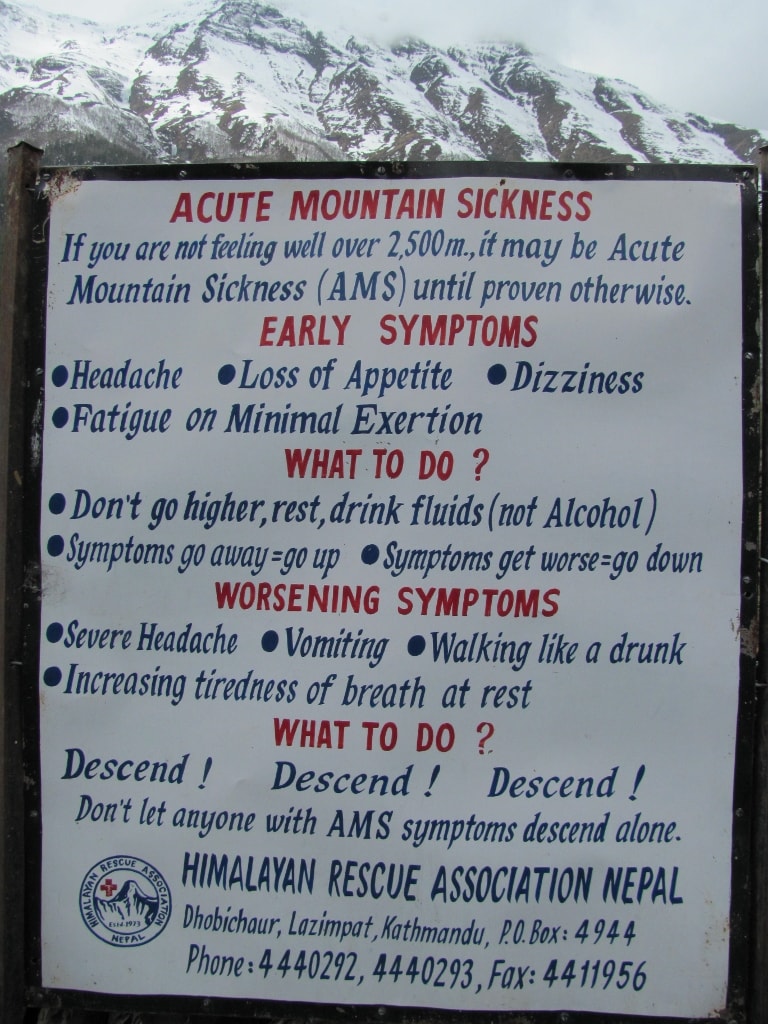

According to the National Outdoor Leadership School: The three main forms of altitude illness are acute mountain sickness (AMS), high altitude cerebral edema (HACE), and high altitude pulmonary edema (HAPE).

Symptoms of AMS include: headache, lack of appetite, dizziness, nausea, insomnia and lack of energy.

The scariest part about the symptoms of altitude illness is that they accurately describe a climbers’ general disposition while high-altitude mountaineering. It becomes rapidly more difficult to make critical decisions in hypoxic (low-oxygen) environments, and sub-par mental function at high altitudes makes HACE and HAPE extremely dangerous. The cure to AMS is to go down in elevation, but that’s a hard choice to make when the whole effort of the mission is to go up. These two sketchy phenomena have caused the deaths of untold numbers of mountaineers throughout history.

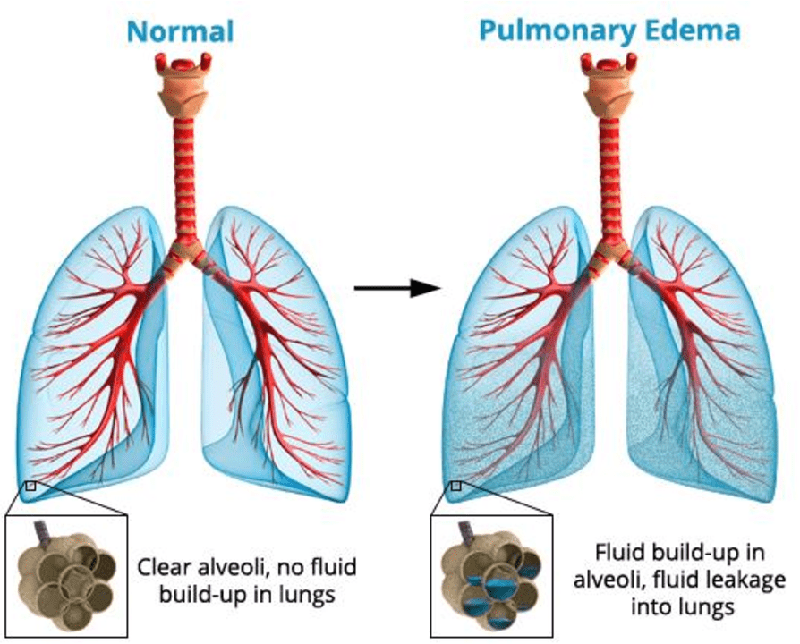

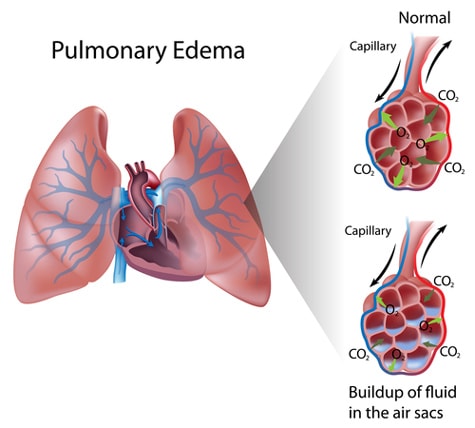

When it comes down to it, the late stages of HAPE look like this: the lungs’ blood vessels and arteries constrict as they adjust to pumping through what minimal fresh oxygen is coming in. This limits the ability to clear fluids out of the respiratory system, which collects inside the lungs. What starts with a cough ends with drowning in your own lung fluid.

The treatment for any sort of mountain sickness and HAPE is the same; the patient must descend. Flurosemide can help, it is a diuretic drug option that treats fluid retention. But this will only buy time, the cure is to get to a more oxygen-rich environment ASAP.