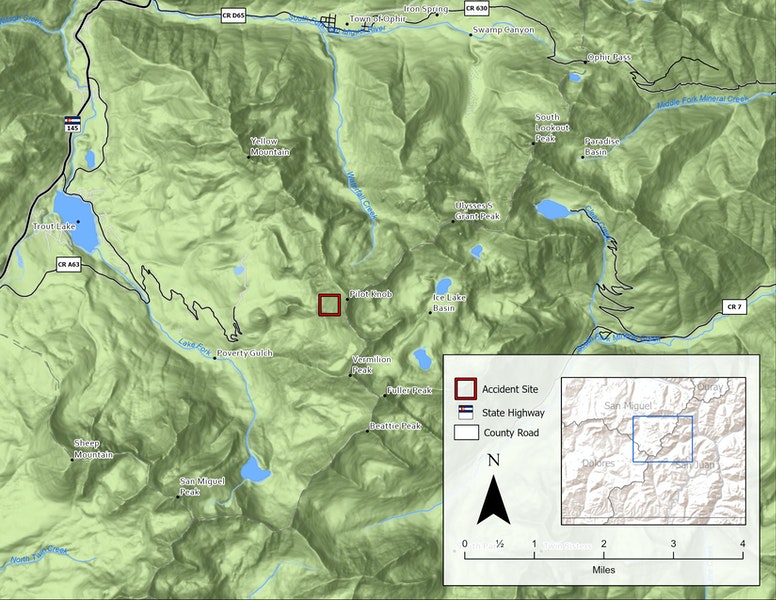

At around 2:00 pm on Thursday, March 17, a solo backcountry snowboarder was caught, buried, and killed in an avalanche south of Trout Lake, 13 miles south of Telluride, CO, in the North San Juan Mountain Forecast zone. The man has been identified as 29-year-old Devin Overton of Telluride, who was “an accomplished backcountry snowboarder,” according to the Colorado Avalanche Information Center (CAIC).

At approximately 3 pm, Helitrax, a local heli-ski outfitter, was flying in the Trout Lake area and spotted what appeared to be evidence of a fresh avalanche. They saw a single set of tracks going into the slide area, but none coming out. They immediately contacted San Miguel Sheriff’s Dispatchers, and a Search and Rescue mission was launched. Helitrax meantime started an aerial beacon search, and when a signal was detected, they landed their helicopter and were able to locate the victim who had been buried under six feet of debris.

Search and Rescue members were flown in to recover the body. On behalf of the entire Sheriff’s Office, Sheriff Masters wishes to extend deepest condolences to Mr. Overton’s family and many friends.

The fatality is the 13th avalanche-related death in the US this winter. Scroll down lower for the full CAIC accident report.

CAIC Report

Avalanche Details

|

Number

|

Avalanche

|

Site

|

Avalanche Comments

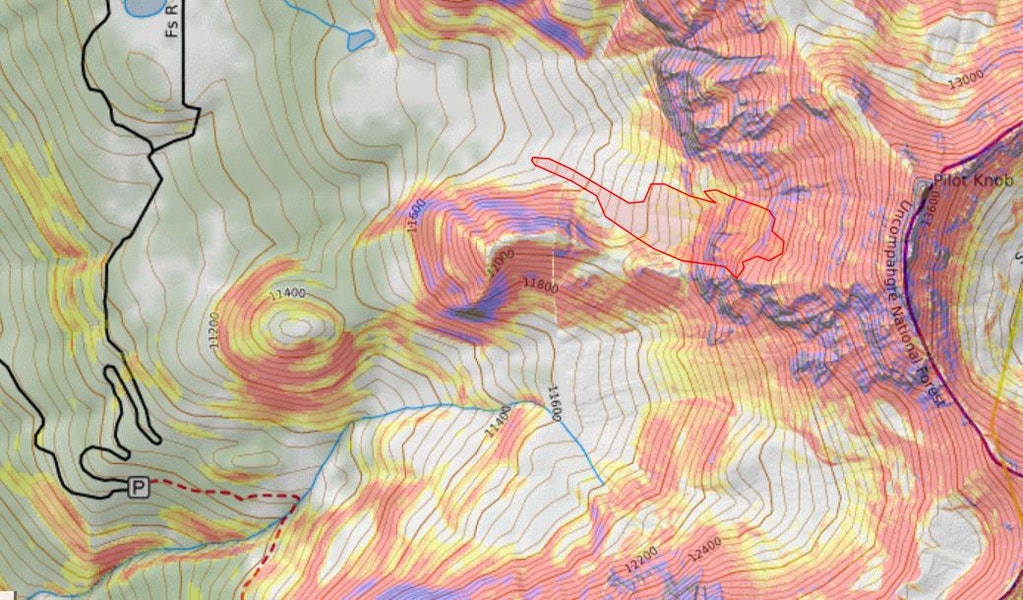

The avalanche occurred on a steep, northwest-facing slope above treeline. It was a soft slab avalanche triggered by a backcountry snowboarder, medium-sized relative to the path, and produced enough destructive force to bury, injure, or kill a person. The avalanche broke 20 to 36 inches deep, on a layer of faceted crystals in the middle of the snowpack (SS-ARu-R3/D2.5-O). As it ran it gouged into old snow layers near the ground in steep terrain features with a shallower snowpack. The avalanche ran 1000 vertical feet on a northwest-facing slope and flowed over two cliff bands and into a slight gully formed by an adjoining north-facing slope. The avalanche debris ranged from two to seven feet deep. The average steepness of the slope in the starting zone was 40 degrees.

Backcountry Avalanche Forecast

The Colorado Avalanche Information Center (CAIC) rated the backcountry avalanche danger in the North San Juan zone at Moderate (Level 2 of 5) at all elevations on the day of the accident. Persistent Slab avalanches were the only avalanche problem. The likelihood of triggering was Possible, with the size Small to Large. The summary statement read:

The primary avalanche concern is triggering a slide that breaks 2 to 3 feet below the surface on northerly and east-facing slopes. With dense slabs above weak collapsible layers, upper elevation slopes are the most worrisome spots. A slide triggered on a wind-drifted slope could break at your feet or from a distance, be more significant than you expect, and be a challenge to escape.

The chances to trigger one of these larger avalanches decreases a bit more each day. You may not get the typical warning signs such as collapses and shooting cracks in the snowpack before triggering an avalanche on these slopes. Use caution on slopes around 35 degrees and limit travel underneath steep, open slopes to avoid this problem.

Weather Summary

The Lizard Head Pass SNOTEL site is 4 miles to the west of the accident site at an elevation of 10,200 feet. Very little snow fell in at the site early in the season with 2.1 inches of snow water equivalent recorded before December 8, 2021. Snow accumulated during three storms from December 8 to January 1, and the SNOTEL gained 7.3 inches of SWE. Snowfall ceased on January 1, and no measurable precipitation fell until February 12. A series of four storms moved through the area from February 21 to March 15, adding 3.4 inches SWE. On March 17, the snowpack was 92% of the median SWE on that date compared to the 1990 to 2020 reference period.

On the morning of March 17, the Telluride Ski Patrol reported 3 inches of new snow with winds switching from the southwest to the northeast by 6:00 AM. Skies were partly cloudy and clearing during the day, wind speeds were light with gusts between 20 and 30 miles per hour.

Snowpack Summary

January through early February was dry and windy, with cold, clear nights. A layer of near-surface faceted crystals formed in the upper snowpack. This layer was around 15 cm deep and was buried by snowfall on February 21. Four storms followed, and by March 17 the near-surface faceted layer was buried under 50 to 80 cm of settled snow. The CAIC documented nineteen human-triggered avalanches between March 1 and March 16 in the North San Juan forecast zone. The majority of those avalanches were triggered on northerly-facing slopes above treeline and ranged from small (Destructive Size 1) to large (Destructive Size 2.5).

Events Leading to the Avalanche

Rider 1 traveled alone on the day of the accident. Investigators reconstructed his route based on his tracks and GPS data.

Rider 1 left the parking area located at the end of winter maintenance on Trout Lake Road, east of State Highway 145. He ascended east to an unnamed basin between Yellow Mountain and Pilot Knob. Rider 1 climbed and descended two south and southwest-facing couloirs before traveling toward the more west and northwest-facing slopes below Pilot Knob.

Accident Summary

There were no witnesses to the avalanche.

Rescue Summary

Around 2:35 PM a guide from Helitrax, a Telluride-based helicopter skiing service, saw a fresh avalanche below Pilot Knob. There was one set of tracks entering the avalanche debris, and no tracks exiting. The guide conducted a transceiver search from the air and detected a faint signal. Helitrax quickly flew clients to a safe location, alerted the San Miguel Sheriff’s Office, and brought in two guides to conduct a transceiver search on the ground.

The guides isolated the transceiver signal with the lowest reading of 2.3 meters. They struck Rider 1’s boots with a probe pole. Helitrax flew in four additional rescuers, and the six worked for about an hour to excavate Rider 1. He was buried over two meters deep, just a meter from the left edge (facing downhill) of the avalanche debris, where the debris piled deeply against an adjacent north-facing slope. Helitrax flew Rider 1 and all of the rescuers out by 5:15 PM.

Comments

All of the fatal avalanche accidents we investigate are tragic events. We do our best to describe each one to help the people involved and the community as a whole better understand them. We offer these comments in the hope that it will help people avoid future avalanche accidents.

Rider 1 was traveling alone. While traveling in a group provides more resources and additional rescue options if something goes wrong, traveling in the backcountry solo is a personal choice. Rider 1 was an accomplished backcountry snowboarder, with a high risk tolerance. He was comfortable traveling alone and did so regularly.

Rider 1 made two runs on south and southwest-facing slopes before the avalanche accident. By the afternoon, rising temperatures and clear skies may have driven Rider 1 off the sunny slopes and on to cooler, northerly terrain where the Persistent Slab avalanche problem was most dangerous.

Rescuers found Rider 1 without his snowboard or climbing skins. He was wearing a base layer and no outer layers. That suggests Rider 1 was either climbing or preparing to go back downhill when he was caught by the avalanche. Rider 1’s burial location, GPS track, and equipment scattered in the avalanche debris indicate he was above the small couloir in the second cliff band when the avalanche occurred.

The avalanche broke on a layer of buried near-surface facets, a persistent grain type. The snow depth, and thickness of the layers above the facets, varied significantly across the slope. Rider 1 may have triggered the avalanche in a rocky area with a shallow snowpack, where the faceted layer was closer to the snow surface and an avalanche was easier to trigger. Avalanches on persistent weak layers are notoriously fickle and it can be challenging to assess slope stability.

The avalanche debris ran down the slope Rider 1 had ascended and pushed up against adjacent terrain at the bottom. This created a terrain trap, where the debris piled deeper than if it ran out onto a low-angle slope. This produced a fairly deep and thus very dangerous burial. Rider 1 was traveling alone and there was no one with him to call for help. Despite this, good work from the Helitrax operation led to a fairly rapid response to this accident. Even with this rapid response, it took over an hour to excavate Rider 1 from the avalanche debris.

Media