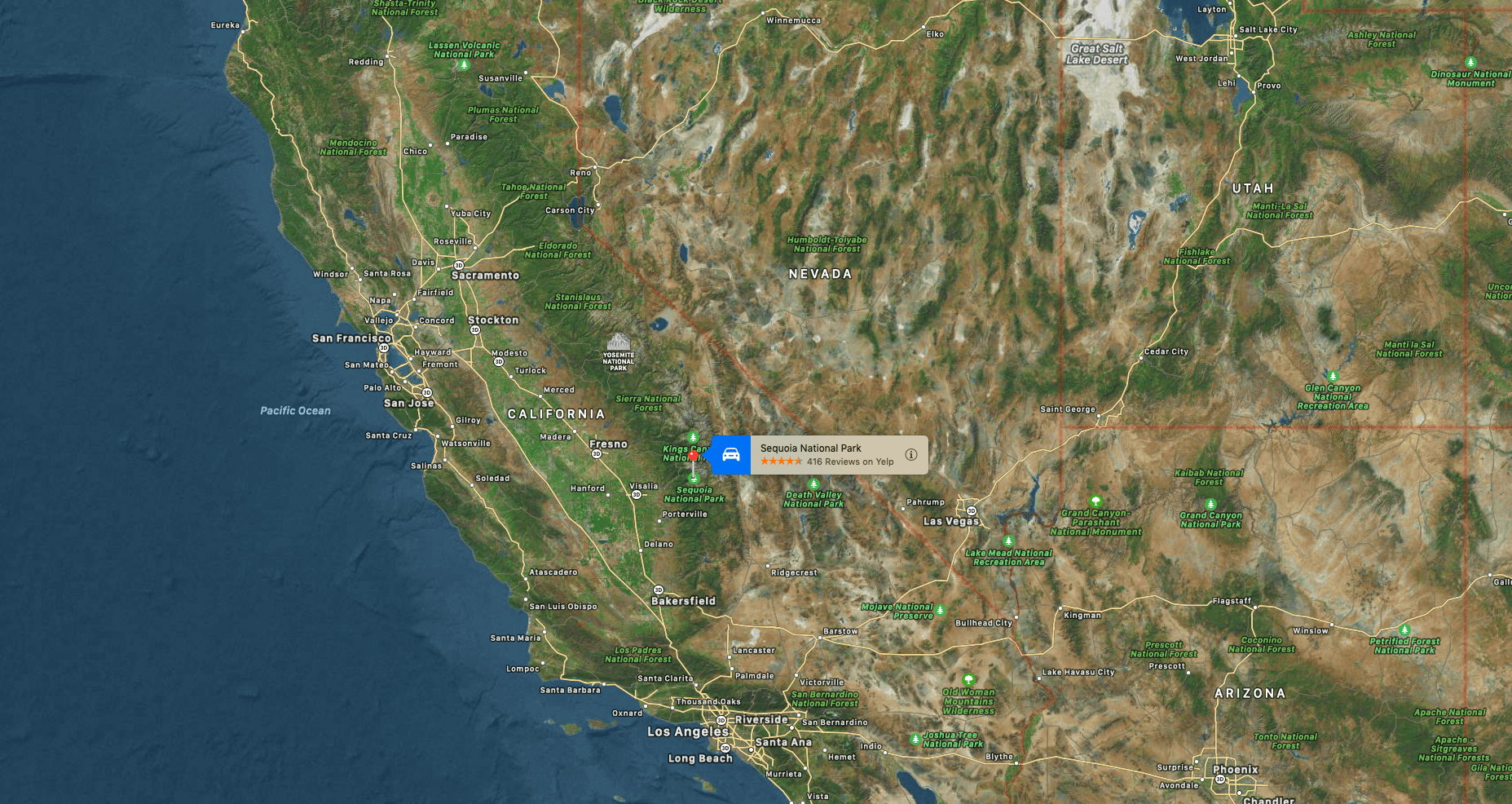

California condors have been seen in Sequoia National Park for the first time in nearly 50 years, reoccupying parts of their historic range. These giant birds are recovering lost historical habitat as the species teeters on the brink of extinction.

According to the National Park Service, the Condors were spotted atop Moro Rock, a popular hiking destination in Sequoia National Park, in late May 2020.

“Condors were constantly seen in all parks until the late 1970s. Observations became increasingly rare during the latter part of the century as the population declined.”

– Said Tyler Coleman, a wildlife biologist at Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks.

The California condor, Gymnogyps californianus, is one of the largest flying birds in the world. When it soars, the wings spread more than nine feet from tip to tip. Condors can soar and glide for hours without beating their wings. After raising thousands of feet overhead on air currents, California condors will glide long distances, sometimes at more than 55 miles per hour. From the air, they search for dead animals, like deer or cattle. They feed only on carrion (dead animals that they find).

Thousands of years ago, California condors lived in many parts of North America, from California and other Pacific states to Texas, Florida, and New York. As people settled across the West, they often shot, poisoned, captured, and disturbed the condors, collected their eggs, and reduced their food supply of antelope, elk, and other large wild animals. Eventually, condors could no longer survive in most places. By the late 1900s, the remaining individuals were limited to the mountainous parts of southern California.

Condor nest sites are in cliff caves in the mountains. Some condors have nested in large cavities in the trunks of giant sequoia redwood trees. Nesting condors raise only one chick at a time. The four-inch-long egg is laid in late winter or spring, and it takes two months to hatch. It takes more than a year from the time the egg is laid until the young bird has learned to live on its own.

In the 1970s, biologists found that only a few dozen condors remained in the wild. In 1980, a major conservation project was started to try to keep the birds from becoming extinct. Many special studies were made. Radio transmitters were placed on the wings of some of the condors. Wild eggs were collected and hatched at the Los Angeles Zoo and San Diego Wild Animal Park, and this helped to increase the population. A few birds were taken to the zoos for captive breeding.

In the mid-1980s all of the remaining condors in the wild were captured and taken to zoos. According to the park service, by 1982 the wild population was reduced to 22 birds, all of which were eventually trapped and brought into captivity to prevent the extinction of the species and save the remaining gene pool for use in a captive breeding program.

“We use GPS transmitters to track the birds movement, which can be over hundreds of miles on a single day.”

– Said Dave Meyer, a California condor biologist with the Santa Barbara Zoo

GPS data produced by these transmitters are used to identify important habitat, locate condor nesting and feeding activity, find sick or injured condors, and locate condors that have died in the wild.

“As biologists, we are excited to see condors continue to expand back into their historic range. And also for the opportunity to engage with the local communities to share what they can do to contribute to the recovery of California condor, and also inform them about threats to these birds.”

– Said Laura McMahon, a wildlife biologist with the USFWS California Condor Recobery Program.