This post first appeared on NASA Earth Observatory and was written by Michael Carlowicz

Just four years after emerging from a punishing multi-year drought, California has descended into dry conditions not seen since 1976-77. Evidence of the new drought stands out in satellite images of the state’s two largest reservoirs.

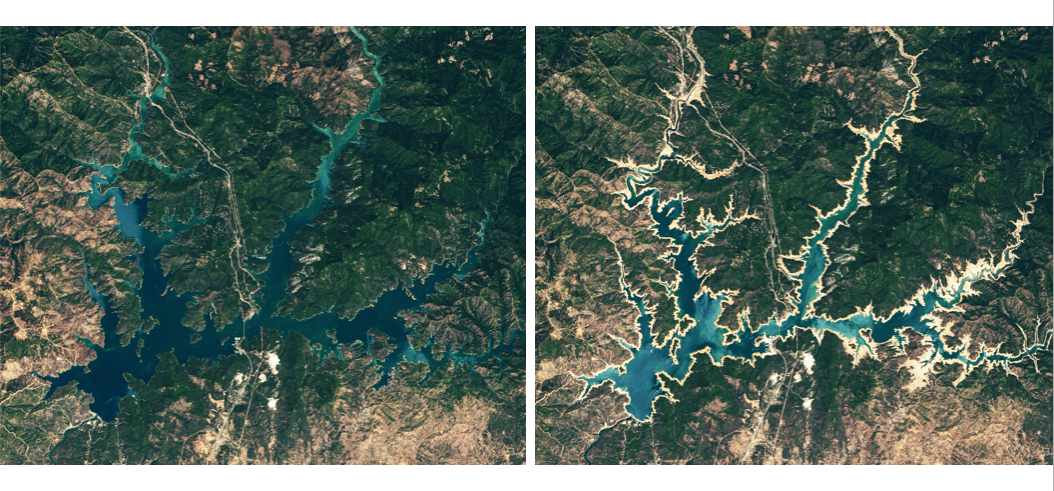

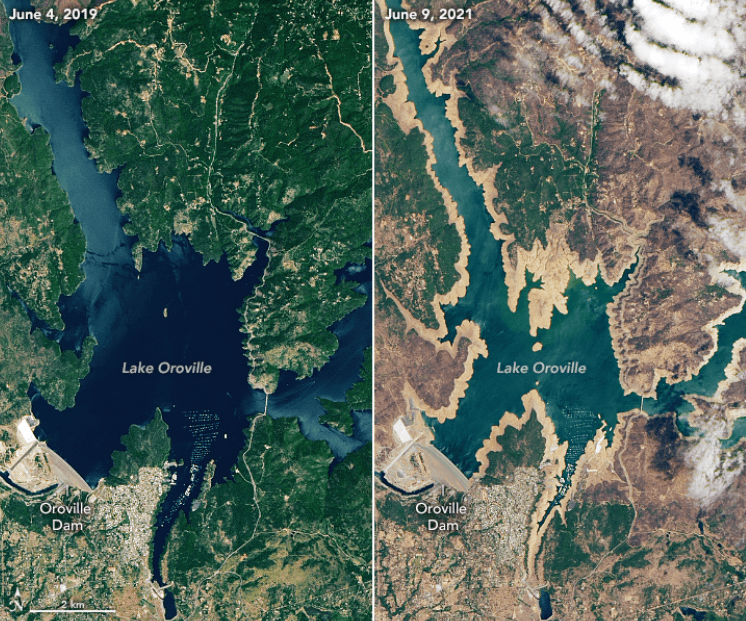

The images above, acquired by the Operational Land Imager (OLI) on Landsat 8, show Shasta Lake and Lake Oroville this year and in June 2019, under more typical conditions. The tan fringes around the water in 2021 are areas of the lakebed that are typically underwater when the reservoirs are filled closer to capacity. The phenomenon is often referred to as a “bathtub ring.”

Managed by the US Bureau of Reclamation, Shasta Lake is the largest reservoir and third largest water body in California. Situated north of Redding, the reservoir feeds into the Sacramento River watershed and is a key water source for the rich agricultural lands of the Central Valley. As of June 16, 2021, Shasta Lake held 1.87 million acre-feet (maf) of water, or about 41 percent of capacity and 49 percent of the historical average for this time of year. However, from the 2019 Landsat image to this week, the lake level dropped 106 feet in elevation.

Lake Oroville, managed by the California Department of Water Resources, has seen a precipitous drop as well. From June 2019 to June 2021, the water level on the state’s second-largest reservoir fell 190 feet, from 895 to 705 feet above sea level. According to the Associated Press, the record low is 646 feet, set in September 1977.

On June 16, Cal Water reported that Lake Oroville stood at 35 percent of capacity and 43 percent of the historical average—just slightly better than the historically dry years of 1976-77. However, according to several news reports, eight out of ten boat launches around Oroville have been closed. Resource managers are concerned that the nearby hydroelectric power plant might have to be idled if water levels drop much more.

Water storage in reservoirs is complicated and not entirely tied to recent conditions. State and federal resource managers adjust water flows to provide water allotments to farmers, drinking water supplies to cities, and the maintenance of watersheds for native and sometimes endangered species. (For instance, salmon need cold water from the bottoms of reservoirs to spawn.) In some parts of California, particularly between Sacramento and San Francisco Bay, water is also managed to prevent saltwater intrusion into freshwater sources.

But even with management for droughts or surpluses, the situation in many California reservoirs is growing quite serious as air temperatures have been unusually warm for months and precipitation has been between 35 to 50 percent normal in many areas. In the Northern Sierra (Sacramento) water region, mean precipitation since October 1 has been 23.1 inches; the average (1966-2015) is 51.8 inches. It has so far been the driest year since the 1976-77 drought. (October 1 is the beginning of the “water year.”) The San Joaquin water region is now in the third driest stretch behind 1976-77 and 2014-15; the Tulare Basin has seen its least precipitation on record. These rain and snow deficits well-below average totals in 2019-20.

The reservoir deficits have been exacerbated by a lack of snowmelt running down from the Sierra Nevada range. Mountain snowfall was already below average this winter, and much of it melted quickly amid high spring temperatures. Large volumes of meltwater were also absorbed by soils that were still parched from last year, and spring heat forced farmers downstream to water some crops earlier and heavier than usual. Altogether, water authorities estimate anywhere from 500,000 to 800,000 acre-feet of meltwater never made it out of the mountains. (One acre-foot can supply roughly two households with water for one year.)

The state government has issued drought proclamations for 41 of California’s 58 counties, and people in many communities are being asked to conserve water. Federal and state authorities have also reduced annual water allocations to farmers and cities in several areas. The cutbacks will likely remain in effect until winter rain and snow falls.