Related Article: Vail, CO Resident Killed in Avalanche in Backcountry Outside Beaver Creek Resort

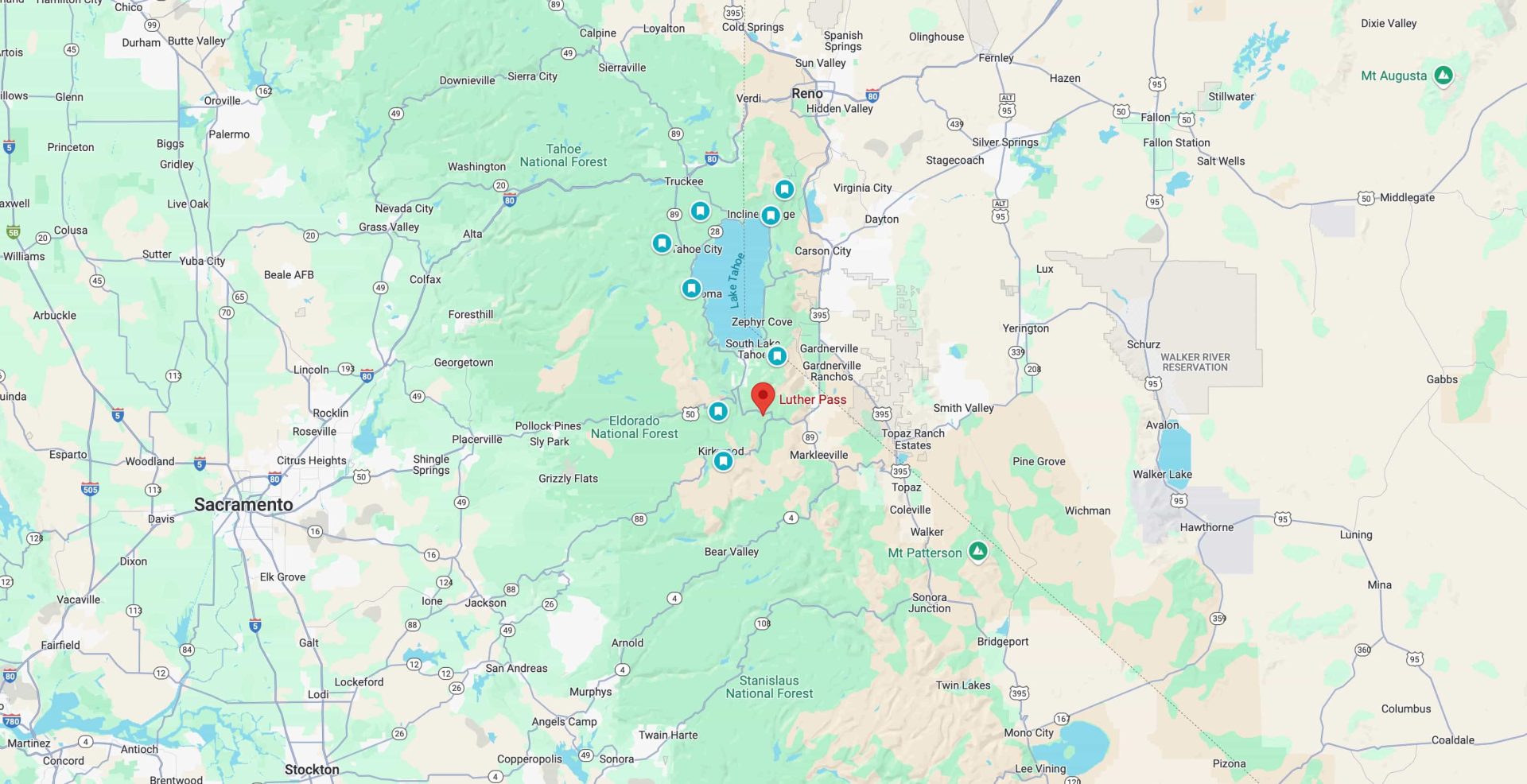

The Colorado Avalanche Information Center today released the full accident report on the avalanche fatality that occurred in the Lime Creek area on March 22, 2021. Gary Smith, 37 of Vail, was the 35th person in the United States to die in an avalanche this season, and the 12th in Colorado, which makes 2020-2021 tied for the most deadly avalanche total in a season in the state. Smith was killed in a relatively small slide outside of the Beaver Creek Ski Area boundary in complex, very steep terrain. The soft slab avalanche was in a north-west facing chute below treeline, where the avalanche hazard had been rated to be generally low. This incident clearly illustrates that Low rating in the avalanche forecast does not mean that the snowpack is 100% safe. In fact, that day’s Forecast Summary stated:

New snow and wind have added the potential for you to trigger small avalanches. You can trigger avalanches on steep, north to east-facing slopes where you find freshly drifted snow. You may see shooting cracks and a find a generally stiffer feel to the surface snow. Although avalanches in the new snow will not be particular large, they can knock you off of your feet and take you for a dangerous ride.

If you are traveling areas with a shallow snowpack, less than about three feet of snow, there is still a chance you can trigger an avalanche that breaks at the ground. Very steep, rocky, slopes with stiff layers in the middle of the snowpack are the most suspect.

As reported in the Colorado Sun and the Vail Daily, Gary Smith was a highly experienced backcountry skier. A former ski patroller, Smith was respected as a great backcountry gear resource at Cripple Creek Backcountry in Vail, CO, and was known as a motivated, talented, and prolific backcountry skier who had skied much of the terrain in the Gore and Sawatch Ranges, as well as all over the Western US, Alaska and Central America.

Significantly, of the 19 people caught and 12 people killed in Colorado this season, skiers account for 14 of the avalanche involvements and 10 of the deaths. In the US, skiers and snowboarders make up 22 of the 36 deaths so far this season. Several of these incidents have involved several people who have been buried and killed, but by and large, most fatal avalanche incidents involve a single victim.

Gary Smith was killed after crossing what the CAIC report said was a permanently closed boundary at Beaver Creek near the top of the Larkspur Express Lift. His avalanche involvement was only partially witnessed by his partner, who saw a snow dust cloud soon after Smith went out of sight 4-5 turns below him. Smith was carried through a steep rock-walled chute and over a 75′ cliff and buried under about 2′ of debris. His partner triggered another small avalanche while performing his companion rescue search and was eventually able to locate and extricate him using his transceiver, probe, and shovel. Gary Smith was dead when his partner uncovered him.

This incident, as with many others this season, has some good lessons to be learned from. You can be involved in an avalanche that has the potential to injure or kill you even on Low hazard days. Small avalanches in complex terrain are difficult to predict, challenging to manage, and have the very real potential to injure or kill you. Terrain management is the key to survival when skiing in avalanche terrain. Even with an experienced partner and efficient companion avalanche search and rescue, the consequences of even a small avalanche can be fatal.

Gary Smith was skiing the sort of terrain many of us have skied in similar circumstances, and usually, we’ve gotten away with it. I refuse to judge or second-guess Smith or any of the other people who have been killed in preventable fatal avalanche incidents this season. I choose to honor them by learning something new from what happened to them and trying to pass some of that knowledge along to other folks. I offer my sincere condolences to the friends and families of all of those affected by this unusually busy and deadly avalanche season. Teton Gravity Research had a good piece that addresses this issue last month that is worth a read.

CAIC Avalanche Forecast and Lime Creek Accident Report – March 22, 2021

All CAIC accident reports are available on the CAIC website. The Lime Creek incident report is quoted in full below:

Avalanche Comments

This avalanche occurred in a very steep, northwest-facing chute in the below treeline elevation band. It was a soft slab avalanche unintentionally triggered by a skier. It was small relative to the path and produced enough destructive force to bury, injure, or kill a person. The slab broke in layers of old snow near the ground, and was about 3 feet deep, 25 feet wide, and 40 feet long. The avalanche ran about 1,000 vertical feet (SS-ASu-R1-D2-G).

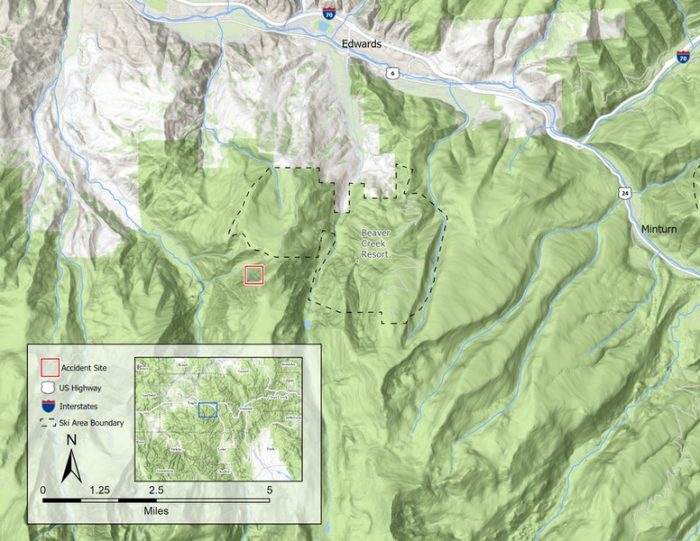

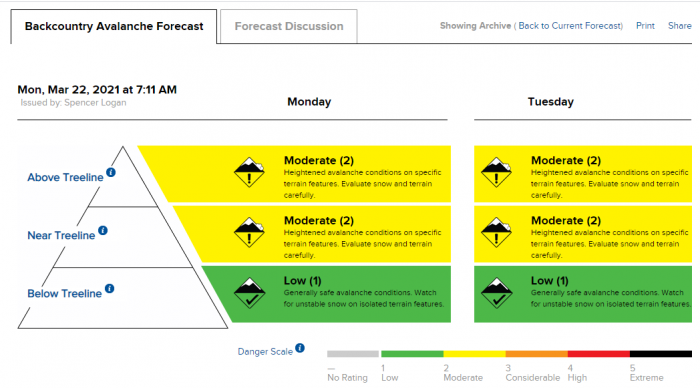

Backcountry Avalanche Forecast

The Colorado Avalanche Information Center forecast for Vail & Summit County zone on March 22 rated the avalanche danger as MODERATE (Level 2 of 5) near and above treeline and LOW (Level 1 of 5) below treeline. Wind Slab avalanches were the first problem listed, highlighted on north, northeast, and east aspects near and above treeline. The likelihood was Possible and the Size Small. Persistent Slab avalanches were the second problem highlighted near and above treeline on west through north to southeast aspects. The likelihood was Unlikely and size Small to Large (up to D2). The summary stated:

New snow and wind have added the potential for you to trigger small avalanches. You can trigger avalanches on steep, north to east-facing slopes where you find freshly drifted snow. You may see shooting cracks and a find a generally stiffer feel to the surface snow. Although avalanches in the new snow will not be particular large, they can knock you off of your feet and take you for a dangerous ride.

If you are traveling areas with a shallow snowpack, less than about three feet of snow, there is still a chance you can trigger an avalanche that breaks at the ground. Very steep, rocky, slopes with stiff layers in the middle of the snowpack are the most suspect.

Weather Summary

Early snowfall in October and November was followed by extended periods of dry weather in December and January. That created an especially shallow, weak snowpack below treeline. On February 1, 2021, there was only 24 inches of total snow depth at the McCoy Park SNOTEL site, located at 9,480 feet, approximately 2.2 miles north of the accident site. The McCoy Park SNOTEL recorded 29 inches of snow in multiple storms during February. The total snow depth was 36 inches on March 1. The McCoy Park SNOTEL recorded 13 inches of snow and 1.3 inches of snow water equivalent in the 10 days before the accident, but the total snow depth was still only 36 inches on March 21.

Winds were calm, averaging less than 5 mph for the 24 hours before the accident. Nighttime low temperatures were in the low 20s Fahrenheit. Daytime high temperatures reached just above freezing on March 22. The surface snow on northerly-facing aspects remained cold and dry. Low clouds drifted in and out throughout the day, with prolonged periods of poor visibility.

Snowpack Summary

The snowpack near the avalanche site was thin and weak. The total snow depth adjacent to the crown was between 100 and 125 cm (between 40 and 50 inches). Boot penetration was to the ground adjacent to the starting zone and adjacent to the runout. Investigators found it was easy to push their ski poles the entire way through the snowpack. The avalanche’s failure plane was a 10 cm thick layer of depth hoar at the ground that formed in early October and November and persisted in colder northerly-facing aspects. Above the depth hoar, there was 40 to 50 cm of weak faceted crystals 1 to 4 mm in extent; this layer formed during extended dry periods in December and January. Above the faceted crystals was a soft (1F to 4F on the hand-hardness scale), 20 cm thick layer composed of rounding grains and small faceted crystals. The upper layer of the snowpack was about 25 cm thick. It was soft (F on the hand-hardness scale) and composed of decomposing and fragmented precipitation particles. Investigators saw evidence of previous wind-drifting on a ridge near the starting zone.

Events Leading to the Avalanche

On March 22, Skiers 1 and 2 exited the Beaver Creek ski area through a permanently closed boundary near the top of the Larkspur Express Lift. They traversed west and made one ski run down low-angle west to southwest-facing terrain in the Lime Creek drainage. They then ascended to a saddle at approximately 10,400 feet in elevation. From the saddle, they turned southeast into a wooded area and continued to ascend through low-angle trees until they gained the ridge. The pair followed the ridgeline southwest for about a half-mile until they arrived at the top of the chute.

The two skiers traversed through sparse trees along the ridge above the steep starting zone, trying to find the best way to enter the chute. They stopped at a few places and assessed the snowpack depth with their avalanche probes. Skier 2 recalled measuring about 150 centimeters of total snow depth. They continued traversing down the ridge to an area on the skier’s left side of the starting zone and prepared to descend.

Accident Summary

Skier 1 began to descend the skier’s left side of the chute. He made four or five turns before dropping out of Skier 2’s view. Moments later, Skier 2 saw a powder cloud and realized there had been an avalanche in the chute.

Skier 1 triggered a small avalanche that broke near the ground on the chute’s rocky left edge. The avalanche carried Skier 1 through a narrow rock-walled gully and over a 75-foot cliff. The avalanche stopped about 1,000 feet below the ridgeline.

Rescue Summary

Skier 2 began to descend the chute. He made a few turns to the skier’s right of Skier 1’s tracks. Skier 2 triggered a second small avalanche upper layer of recent snow. He was caught but skied hard right toward the edge of the chute and out of the second avalanche.

Skier 2 made his way down to the top of the cliff. He found no sign that Skier 1 had exited the chute above the cliffs. Skier 2 descended to the right around the cliffs. When he got to the bottom of the cliff band, he still could not find Skier 1. Skier 2 turned his avalanche transceiver to search and began to descend the narrow avalanche path. Skier 2 got a signal on his transceiver and was able to locate Skier 1 quickly. The avalanche had completely buried Skier 1 under about two feet of debris. Skier 2 uncovered Skier 1, but unfortunately, he was not alive.

Skier 2 made his first 911 call to report the accident at 2:12 PM. Poor cell phone reception prevented Skier 2 from communicating clearly. Unsure of the rescue, Skier 2 put on his skins and began to ascend the Lime Creek Drainage toward the ski area. The Eagle County Sheriff’s department determined Skier 2’s location from his cell phone signal. The Sheriff’s Department alerted the Beaver Creek Ski Patrol and the Vail Mountain Rescue Group about the avalanche accident.

Beaver Creek Ski Patrol began the initial rescue at 3:03 PM. At 3:46 PM, ski patrollers left the ski area boundary to assess the accident site. In the meantime, Skier 2 arrived back in the ski area and provided additional details about Skier 1’s condition and the accident location.

Around 4:00 PM, searchers reached Skier 1 and confirmed he was deceased. Beaver Creek Ski Patrol used a snowcat with its winch attached to a tree to transport the patrollers and Skier 1 back to the ski area.

Comments

All of the fatal avalanche accidents we investigate are tragic events. We do our best to describe each one to help the people involved, and the community as a whole better understand them. We offer these comments in the hope that they will help people avoid future avalanche accidents.

It is important to understand that you can trigger dangerous avalanches even at a LOW (1 of 5) avalanche danger. The Avalanche Size and Distribution column in the North American Public Avalanche Danger Scale for LOW danger says backcountry travelers may encounter, “Small avalanches in isolated areas or extreme terrain.” Extreme terrain is generally 45 degrees or steeper and often has additional features like cliffs or rocky chutes. You need to carefully assess the danger on specific slopes before you commit to traveling in extreme terrain.

Traveling above terrain traps such as cliffs or trees always increases the chance for a bad outcome if you are caught in an avalanche. It does not take a very big avalanche to knock you off your feet and send you for an uncontrollable ride. It is important to know what is below you before you ride in steep avalanche terrain..

Beaver Creek Ski Patrol contributed to this accident investigation. We greatly appreciate their assistance.