In one of the final chapters of his book, The Art of Shralpinism, snowboarding pioneer Jeremy Jones writes about inclusion and programs that bring marginalized communities in the United States and South America into an international community of snowboarders. This got me thinking about inclusion in a Canadian context. In Canada, the idea of inclusion immediately calls up this country’s long history of egregious treatment towards Indigenous People in the name of assimilation, and efforts in recent years towards reparation and reconciliation. I wanted to understand the perspective of an Indigenous pro athlete who had been competing in my sport, snowboarding, from the beginning, and long before there was an international dialogue about inclusion, or specific programs in place supporting athletes from marginalized communities. This led me to reach out to Brett Tippie via his Facebook page, and after a back and forth on email, Brett graciously agreed to meet with me on Zoom. We spoke for nearly three hours.

For a country that is recognized internationally for its peacekeeping and humanitarian efforts, Canada has a dark and sordid past in relation to the treatment of First Nations, Metis, and Inuit people within its own borders. Between 1870 and 1997, over 150,000 First Nations, Metis, and Inuit children were separated from their families and forced to attend Christian faith-based, government-funded schools founded on the premise of assimilating Indigenous children into the ruling white culture. In 2015, the federal government of Canada appointed a Truth and Reconciliation Commission, tasked with investigating these atrocities. They concluded that Indigenous children were physically and sexually assaulted in the schools, dying in numbers that may never fully be known.

Intergenerational trauma caused by residential schools and structural racial discrimination has led to a number of present-day human rights violations and abuses in Canada, including the current crisis of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls. In a report published in 2019, the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Women and Girls estimated that Indigenous women and girls are twelve times more likely to be murdered or go missing in Canada, violence that they concluded amounts to genocide. While there have been federal, provincial, and local efforts to address past atrocities, challenges to undoing decades of structural and systematic discrimination remain at all levels of government in this country.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission published several volumes of reports in both official languages in December 2015. The report itself is brilliantly and beautifully written. It contains numerous first-person testimonies, at times heart-wrenching, that serve as a historical document of Canada’s complicated residential school legacy. The TRC report also includes a number of calls to action toward reconciliation with Indigenous Canadians and the inclusion of First Nations, Metis, and Inuit cultures, rights, and treaties into the cultural and political fabric of Canada. The full report is available to read online as an open-access document, and I urge everyone, not just every Canadian, to read it.

Because this is a forum about sport, and because athletes from Canada’s Indigenous communities have represented this country, excelling in a variety of sports on the international stage, across history, and against the odds, I wanted to know what the TRC report said about athletics. A section of the report entitled Sports: Inspiring Lives, and Healthy Communities identifies that many survivors of residential schools testified that playing sports made their lives more bearable, and gave them a sense of identity, accomplishment, and pride. The TRC recognizes that sport is a place where we speak a universal language – a language of a shared passion for our moving bodies through time and space, with strength and skill, and their report lists a number of calls to action related to sport, including:

“87) We call upon all levels of government, in collaboration with Aboriginal peoples, sports halls of fame, and other relevant organizations, to provide public education that tells the national story of Aboriginal athletes in history.”

“88) We call upon all levels of government to take action to ensure long-term Aboriginal athlete development and growth, and continued support for the North American Indigenous Games, including funding to host the games and for provincial and territorial team preparation and travel.”

“89) We call upon the federal government to amend the Physical Activity and Sport Act to support reconciliation by ensuring that policies to promote physical activity as a fundamental element of health and well-being, reduce barriers to sports participation, increase the pursuit of excellence in sport, and build capacity in the Canadian sport system, are inclusive of Aboriginal peoples.”

“90) We call upon the federal government to ensure that national sports policies, programs, and initiatives are inclusive of Aboriginal peoples, including, but not limited to, establishing:

- In collaboration with provincial and territorial governments, stable funding for, and access to, community sports programs that reflect the diverse cultures and traditional sporting activities of Aboriginal peoples.

- An elite athlete development program for Aboriginal athletes.

iii. Programs for coaches, trainers, and sports officials that are culturally relevant for Aboriginal peoples.

- Anti-racism awareness and training programs.”

“91) We call upon the officials and host countries of international sporting events such as the Olympics, Pan Am, and Commonwealth games to ensure that Indigenous peoples’ territorial protocols are respected, and local Indigenous communities are engaged in all aspects of planning and participating in such events.”

Long before I started thinking about inclusion in any real sense, I knew that I wanted to write an article that features the stories of Indigenous pro snowboarders. Still guided by echoes of appropriation, a key theme from my own formal education in the social sciences and humanities in the early 1990s, I didn’t know where to start, or honestly, if I should even attempt to write down these stories at all. Decades later, and nearing a decade since the publication of the TRC’s report, I hope that telling these stories and raising awareness about the experiences of Canada’s Indigenous people trumps concerns about who is doing the telling.

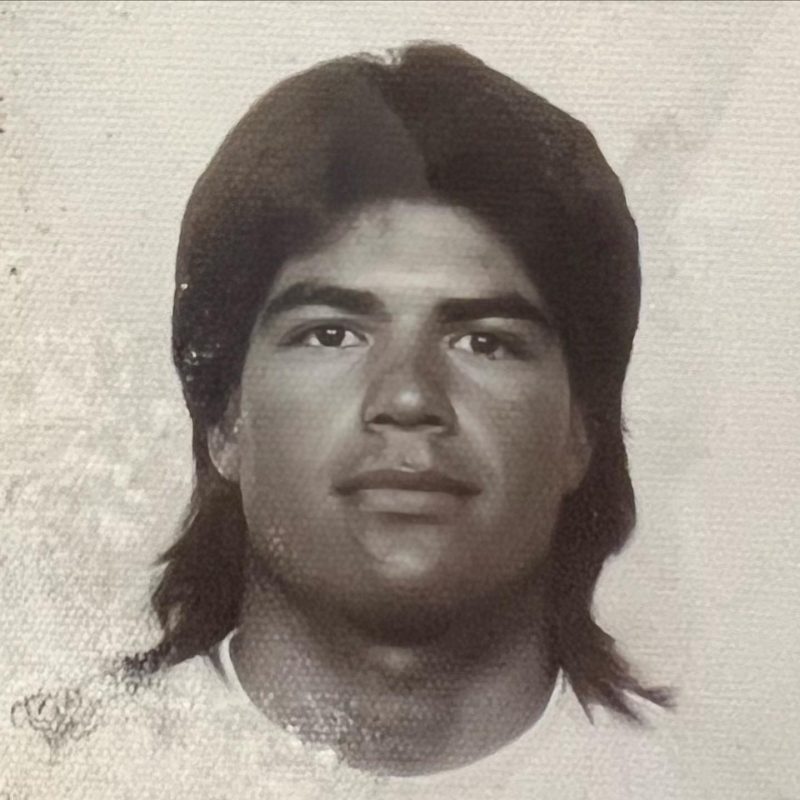

Brett Tippie is on record as the first Indigenous professional action sports athlete in Canada, having competed and filmed in both snowboarding and mountain biking at an elite level for several years, and since the earliest days of both disciplines. Raised in Kamloops, British Columbia (from the Secwepemc word ‘Tk’emlups,’ meaning ‘where the rivers meet’), known as the ‘Tournament Capital of Canada,’ Tippie is of Metis, Dene, and Cree heritage. His maternal grandmother, who was Dene and Cree, was brought up in a residential school, and before meeting Brett’s Metis grandfather, who the nuns encouraged her to marry “because she would have a better life,” she was herself planning for life as a nun.

For mountain bikers, Brett Tippie needs no introduction. He is instantly recognizable, along with Richie Schley and Wade Simmons, all local boys from Kamloops, as one of the ‘Godfathers of Freeride.’ ‘Brett the Rockstar’ is indeed a founder of professional freeride mountain biking. What is less known is that Brett is equally passionate about snowboarding and started his professional career as a snowboard racer, along with athletes like New Brunswick’s Mark Fawcett, New England’s Jeremy Jones, and the GOAT Craig Kelly.

Brett Tippie’s story in snowboarding is a remarkable one that begins in the blue-collar community of 1980s Kamloops. It includes a chance meeting with Craig Kelly in Rossland, BC in 1991, a Burton sponsorship by 1994, numerous top 10 achievements in World Cup snowboard racing and pro boardercross events, winning the Canadian National Pro Boardercross Championships, and an early stint as a color commentator for The World Cup of Snowboarding on Canada’s CTV Sportsnet Network.

I had a set of questions that I sent Brett before our meeting. We covered the key points, but several times we went off script. More than anything, I felt honored, and admittedly nervous, to have the experience of listening to Brett tell his story in his own words. Our conversation went in many directions, guided by a common love for Canada and snowboarding. We talked about Canada’s record as it relates to Indigenous people, some about Brett’s family history, and most significantly, Brett provided a detailed chronology of his long and successful career as a professional badass in adrenaline-fueled sport. And we shared some laughs. Brett is a born comedian, skilled at the fine art of conversation, with an infectious grin, a signature laugh, and seemingly endless energy.

What inspired you to get involved in snowboarding in the first place, & what led you to become a pro?

“I started at 6 years old as a skier at our local resort in Kamloops, Harper Mountain. When I was thirteen, I saw a tiny ad for a snowboard in a publication called Action Now Magazine. I decided to make my own snowboard in my dad’s woodshop (with some plywood and strips of BMX tires for bindings), based on the picture in the ad, and my limited grade-eight woodshop skills. I’ll tell you something funny … .”

Brett recalled how his dad, who was a high school teacher, came into the woodshop, saw what he was doing, and suggested he try setting bindings sideways on a monoski. Brett defiantly continued to work on his own design, and made several versions, with custom graphics. Fast forward a decade, and sure enough, his dad’s idea of a monoski setup was nearly identical to what Brett would eventually race GS on. I shared my own story about how my mom told me to take a gap year after high school and move out to Banff, Alberta, to work at the hotel and snowboard. Instead, I insisted on going to university in a small town in Ontario, nowhere near any ski resorts. We had a good laugh over that one. The moral of this part of the story? “Listen to your parents.”

Brett eventually replaced homemade boards with Sims and Burton ones, and in 1988, after graduating high school in Kamloops, he migrated to Sunshine Village, Alberta, one of the first big resorts in Canada to embrace snowboarding, and fell in with a community of like-minded riders. That first winter, he worked as a lifty at Sunshine, vowing to himself to never work another winter again. “Worst job ever, loading chairs for hours while wishing other skiers and riders a great powder day, ” he says with that signature laugh and smile.

Can you talk about when you met Craig Kelly and what he stood for to you as a young Canadian athlete?

Brett’s introduction to professional snowboard racing can perhaps be summed up in two short sentences:

“Is that Craig Kelly? That’s Craig Kelly.”

As a snowboarder from Brett’s generation, I was keen to hear about Brett’s chance meeting with his snowboarding hero, and the veritable icon of our sport since its earliest days. In 1991, Brett spotted Craig in Rossland, British Columbia, and immediately struck up a conversation. Craig was standing by his car, looking down, and looking perplexed. He was looking for his car keys that he’d dropped in the deep snow. Brett quickly located the keys, and they spent some time hanging out together, ending with Craig inviting Brett to join the Burton crew on a film shoot the following day. Brett showed up at the agreed meeting spot an hour early, but after several hours, there was no Craig Kelly. Bruised but not broken, the ever-tenacious Tippie decided to shred the line that they had planned to film, solo.

But it wasn’t that Craig was a no-show, he was hours late after partying the night before, and when the Burton crew finally arrived, they suspected that Brett had snaked their line. Later that same evening, Brett was hosting a New Year’s Eve party. Craig walks in with the Burton crew and immediately knees Brett in the thigh, with Brett reacting by putting Craig in a headlock and bumping his head into the fridge. The two athletes quickly realized that what really went down was a misunderstanding, and Brett and Craig became friends. Brett even presented Craig with a custom t-shirt Brett hand-painted to smooth things over.

Craig Kelly recognized how fast and skillfully Brett was navigating the mountain and encouraged him to race at a pro level. He offered to sell Brett the speed suit he won the US Open in for $150. Brett didn’t have it on him, however, so he told Brett to meet him at the next race in Copper Mountain, Colorado. Brett ended up beating Craig’s time in the first run and placing 11th overall. His professional snowboarding career was underway.

While you have superstar status in the world of freeride mountain biking, do you ever wonder what your career would look like now if you had stuck with snowboarding exclusively?

Brett’s career took a sideways turn towards the international stage of freeride mountain biking when he appeared in the 1995 film, Pulp Traction, and more importantly, Christian Begin’s ground-breaking MTB movie, Kranked. In the earliest years of snowboarding, the superstars were made in the half-pipe and the magazines. While Brett received tons of gear and some travel money to race from his sponsor, Burton, his professional snowboarding career was largely funded by tree planting and construction jobs in and around Kamloops in the summer months, his training grounds were the gravel pits outside town. He didn’t have the resources to snowboard year-round, training in far-off places during the summer.

He made do with what he had, shredding sand on bike and board, where he ended up being filmed with other Kamloops locals, “The Fro Riders,” by Christian Begin. Begin’s first big freeride mountain bike film, Kranked, quickly reached an international community of bikers, especially in Europe, where anything to do with bikes is religion, and the rest, as they say, is history. As a professional snowboarder, Brett competed in over 25 World Cup events and represented Canada on the National Team in Snowboardcross and GS, but as a freeride mountain biker, he was a superstar, jumping and landing the world’s biggest cliff drops on a bike for a few years, and traveling around the world to film in exotic places. The universe had sealed his fate.

As we talked, Tippie touched briefly on a time in the early 2000s when a partying lifestyle, drugs, and alcohol nearly took him to the point of no return. He expressed regret for those lost years, “it’s part of the story,” how his dad brought him back from the brink after his grandma passed, but most impressively, how he conquered his addictions in rehab, reemerging on the competitive freeride circuit in his early 40s, in peak form. It was around this time that he met the love of his life, Sarah Fenton Tippie, “the most beautiful woman I’d ever seen” (he tells me that they may have met years earlier), an equally passionate mountain biker, and they started a life together.

Brett and I talked briefly about new and existing programs in Canada that support Indigenous athletes. Awareness is half the battle, and then comes programming and direct financial support. Snowboard Canada funds a program specifically for Indigenous athletes. Canadian Olympic slopestyle rider and six-time X Games medalist Spencer O’Brien, who is Haida and Kwakwaka’wakw, also from British Columbia, and a role model to many young women in sport, is a one-time beneficiary, now an ambassador. Brothers and professional snowboarders from Regina, Saskatchewan, Mark and Craig McMorris have donated funds to aspiring Indigenous snowboarders through their McMorris Foundation, which is guided by a vision of creating a more affordable and inclusive sport culture in Canada. Would Brett Tippie’s career as a professional snowboarder have looked different if programs supporting Indigenous athletes existed in 1980s Kamloops? It’s impossible to say for sure.

Do you feel that, given your profile and long history in action sports, you are in a unique position to advocate for indigenous athletes in Canada? What advice do you have for young people who share your passion for snowboarding?

Brett Tippie has lived and lives a good life, some would say charmed, guided in part by a close-knit, supportive family. He grew up playing sports, he was a high school football star in a tough, mainly ranching and mining community, and the landscape around his home in Kamloops became a canvas for his fearless style of snowboarding and mountain biking. He has a tenacious spirit. His experience is perhaps not the same as other athletes from marginalized communities, but I would argue that in order to achieve true reconciliation and inclusion, it’s important to tell all the stories, the good, the bad, and points in between.

Young athletes thrive when they can look to cultural representation in their chosen sport, and Brett Tippie’s career serves as an inspiration to many. As far as advice for young people, Brett touched on the basics: “Eat well, sleep well, breathe. Look ahead,” he said as he pointed to a quote from his grandfather that he’s remembered at every stage of his career as a professional athlete:

“Live your life like you want to remember it.”

It was an absolute honor and privilege to speak to Brett Tippie (his stories could easily fill a book), and perhaps raise some awareness about the experiences of Canada’s Indigenous pro athletes in the process. Now in his early 50s, Brett has a massive and loyal social media following and is still a sponsored pro athlete in mountain biking and snowboarding. His busy career includes filming, announcing freeride mountain bike and snowboard racing events, interviewing the most famous mountain bikers in the world on his wildly popular Brett Tippie Podcast, and slaying the competition in banked slalom events riding as an ambassador for YES Snowboards. Outside of this hectic schedule, Brett rides the trails around the home that he and Sarah have built in North Vancouver with their two daughters.

Before Brett and Sarah headed out for their morning trail ride, he ended our conversation in true Brett Tippie-style, with some distinctly Canadian humor. Depending on your age, you might remember that snowboarding was first introduced as an official Olympic sport in Nagano Japan in 1998. You might also remember that Brett’s Canadian National teammate, Whistler BC’s Ross Rebagliati, was awarded the gold medal in the men’s snowboard GS event, only to be stripped (temporarily) of his medal after testing positive for cannabis, which the IOC mistook (initially) as a “banned substance.”

Brett: “How many Canadians does it take to win an Olympic Gold medal?”

Me: I don’t know.

Brett: “One, … & an eighth.” “There’s a second part … .”

Brett: “How do you know a Canadian has won the gold medal? When he’s highest on the podium.”