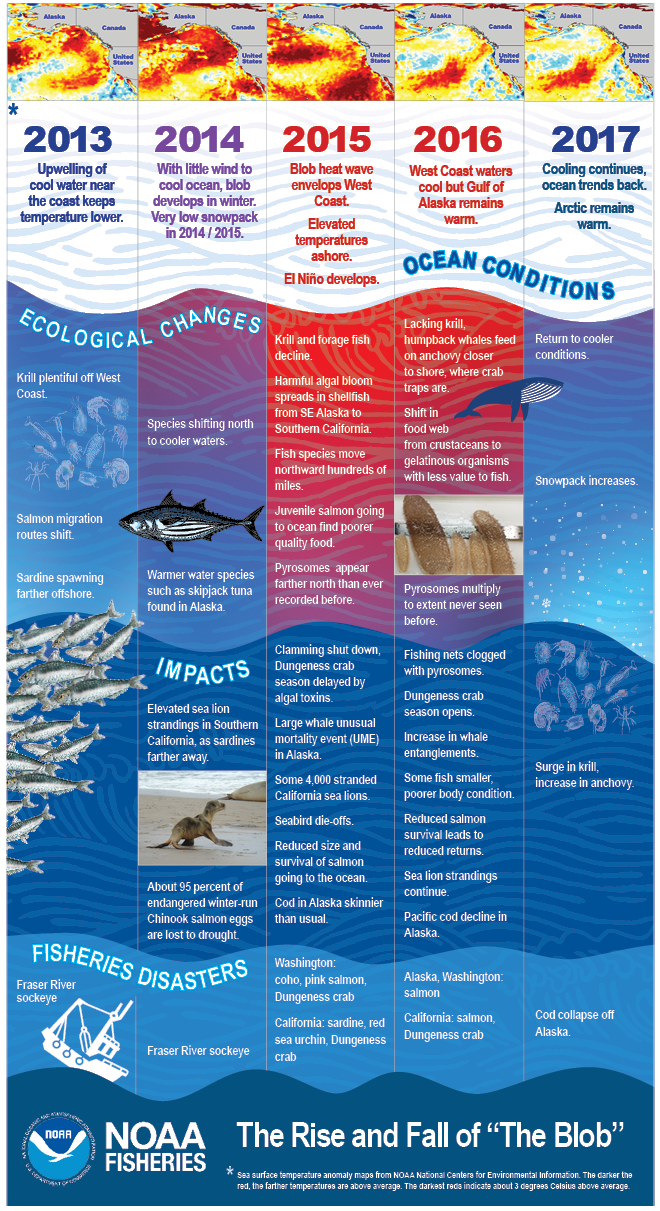

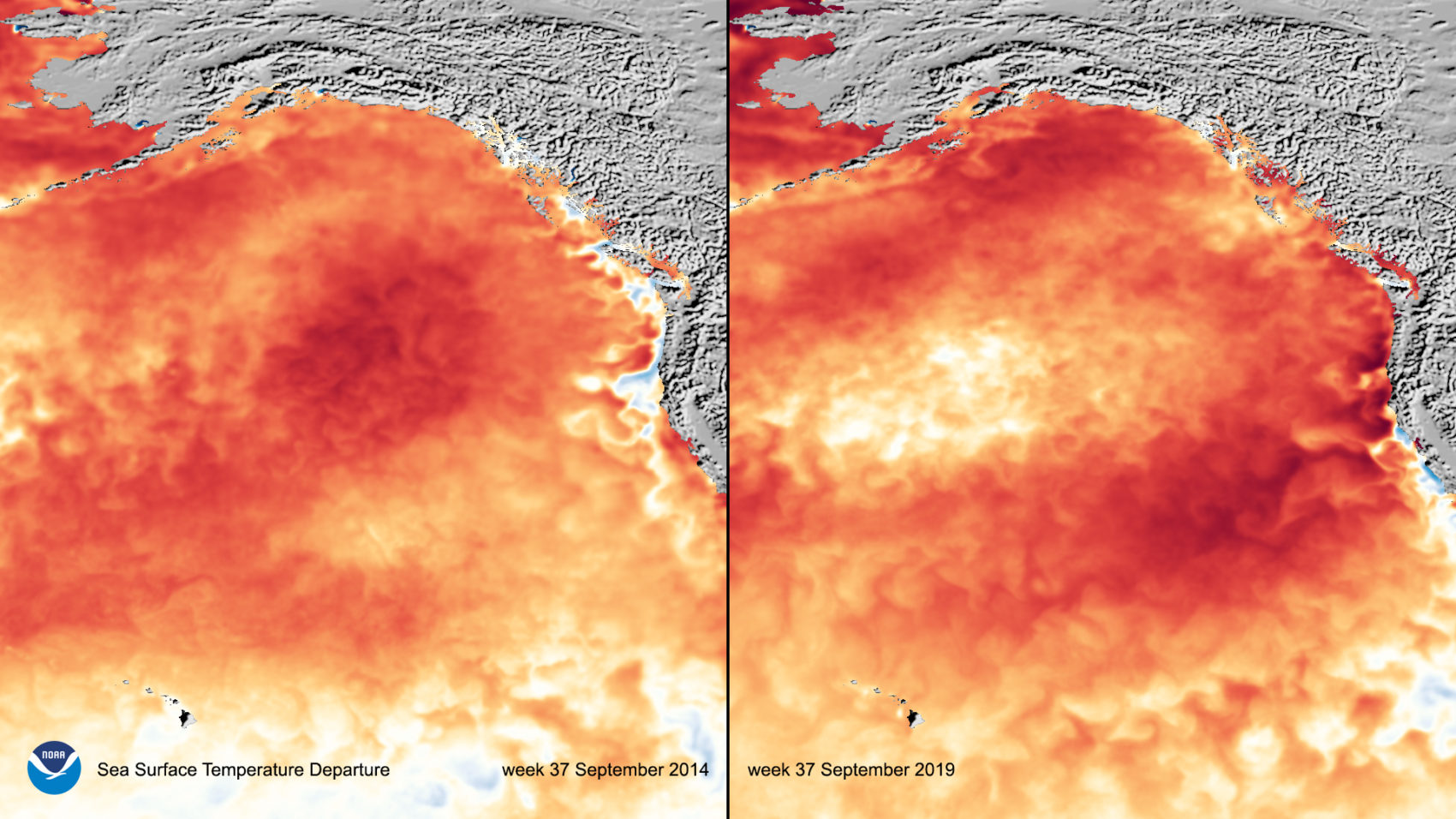

The new marine heatwave off the Pacific Coast is reminiscent of the early stages of the 2014–2016 “blob” that devastated marine life and is believed to have affected the weather. This year’s expanse of unusually warm water stretches roughly from the Gulf of Alaska south to California and west all the way to Hawaii.

These marine heatwaves occur when sea surface temperatures are warmer than 90 percent of past anomalous measurements at a specific location and time of year for more than 5 days. The Northeast Pacific Marine Heat Wave of 2019 (NEP19) was caused by weak summertime winds over much of the Northeast Pacific Ocean. A persistent ridge of high pressure over Alaska and a broad area of lower than normal pressure between Hawaii and the West Coast combined to weaken the normal summertime winds over this region.

“If there’s not enough wind at the surface [of the ocean], you don’t pull as much heat from the ocean into the atmosphere, or mix up the surface water into the deeper, colder water,” explained Andrew Leising, a research oceanographer with NOAA Fisheries’ Southwest Fisheries Science Center in La Jolla, Calif. “So what happens is, that surface layer just starts to heat.”

This year’s marine heatwave certainly mirrors the size of the blob — Leising notes the surface area is about six or seven times the size of Alaska, which covers more than 600,000 square miles. For reference, Alaska is bigger than Texas, California and Montana combined. While the heatwave events are roughly the same size, there are two important differences:

- So far the warm waters associated with the NEP19 have only penetrated a fraction as deep into the water column as those of the blob.

- Unlike the blob, which initially began as two separate marine heatwaves — one in the Gulf of Alaska and one-off of Southern California — and merged during late 2014, this year, the feature off of Southern California was absent during the initial build-up of the marine heatwave.

Effects on Marine Life

The blob of 2014–2016 had a significant impact on the ocean ecosystem up and down the West Coast, prompting everything from toxic algal blooms to massive die-offs of an array of marine life. While the changes in ocean temperature are bad enough on their own, Leising explained that it can really hurt certain fish populations because “a lot of these animals are really keyed in on an absolute temperature.”

During the blob, researchers saw a significant decline in phytoplankton, which serves as the base of the food web. When that happened, Leising said scientists also noticed that once plump, nutrient-rich copepods — tiny crustaceans that eat phytoplankton — began decreasing in abundance and were replaced with smaller, warm-water less-nutritious oceanic species, which was bad news for the larval fish that relied on the cold-water copepods as a source of food. As that part of the food chain crumbled, it impacted seabirds and marine mammals, among others, that also rely on the cold-water-fueled food web.

Gregory Johnson, a researcher with NOAA’s Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory (PMEL), added that the impact was also evident when crab fisheries closed, and reports were issued about marine mammal strandings and mass seabird die-offs.

Although scientists noticed the blob in the spring and summer of 2014, its effects on the ecosystem didn’t actually become evident until 2015, which is why Leising said this year’s heatwave is analogous to 2014.

“Some of these effects might happen sooner than later, but if it were to follow the course of the last event — which we actually don’t think it will, but if it did — we wouldn’t see some of these effects until next summer,” he added.

With that being said, there is already some evidence of a harmful algal bloom off the coast of Washington state.

Tracking Marine Heat Waves

The repercussions of marine heatwaves can be felt by entire marine ecosystems, as well as within the fishing industry, which relies on natural resources for economic stability. That’s why Leising, along with research fishery biologist Greg Williams (NWFSC), and information technology specialist Lynn Dewitt (SWFSC) as part of NOAA’s California Current Integrated Ecosystem Assessment team, are developing an experimental California Current Marine Heatwave Tracker that aims to “help natural resource managers, businesses, and coastal communities anticipate changes and mitigate possible damages in the future.”

Sea surface temperature data from buoys, ships, and satellites are a vital component to tracking this phenomenon. The Advanced Baseline Imager (ABI) aboard the GOES-R satellite series and NOAA-20’s Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) collect this data by looking at the infrared radiation that’s emitted from the ocean.

But scientists don’t rely on sea surface temperature data alone. Johnson explained that an array of Argo floats, that are located roughly every 3 degrees of latitude by 3 degrees of longitude across the ocean are collecting data on the depth of these heatwaves.

“We can make maps of the temperature of the ocean down to 2,000 decibars, which is well below the depth of these particular heatwaves,” Johnson noted. “We can see just how deep the warm anomaly is penetrating and that allows us to track how much is getting in the ocean, and gives us a sense of how much longer it’s going to last.”

Using sea surface temperature data from January of 1982 onward, Leising’s tracker can outline a particular feature if it satisfies the criteria for a heatwave.

“Then once I outline it, I follow it around no matter how it moves around in space or shrinks or expands,” Leising said. “Once I’m able to track them and measure their outline, I can do a lot more analysis on the heatwave.”

The tracker, Leising says, allows him to keep track of how big a marine heatwave is, where it’s located and how close it is to the coastline.

While both Leising and Johnson said it’s hard to predict just when or if this marine heatwave will subside before causing damage to the marine ecosystem, both agreed a strong, cold winter could probably put an end to this year’s event.