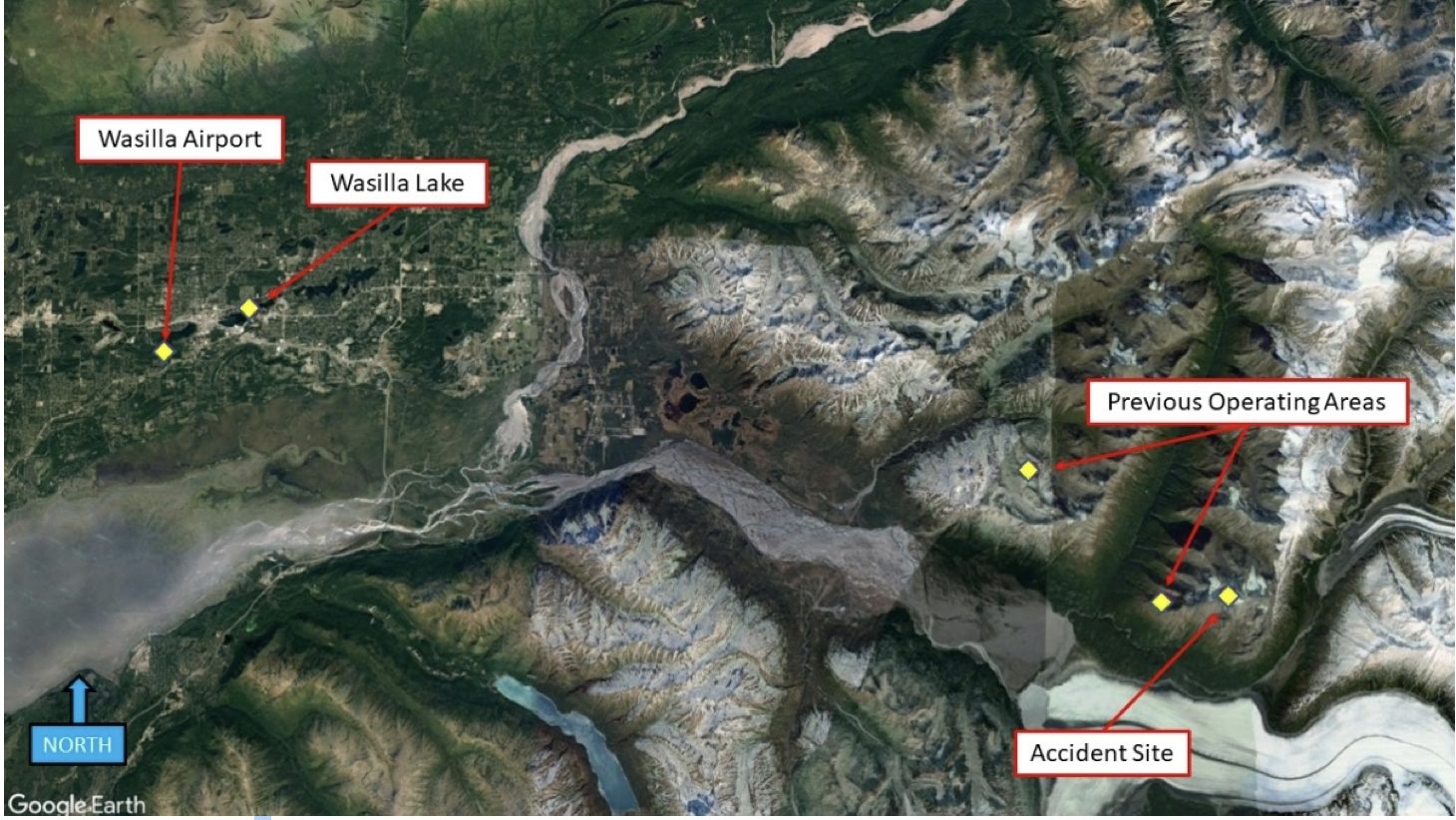

On March 27, 2021, under the bright, deceptive calm of a blue sky, an AStar helicopter carrying six people—three Czech nationals, two American guides, and a pilot—lifted off from Wasilla Lake, heading for the remote, untouched powder of Alaska’s Chugach Mountains. It never returned.

By the end of the day, Petr Kellner, Czechia’s richest man, was dead. So were four others. The lone survivor would later describe in a report shared by the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) as being pinned in the wreckage, buried in snow, listening to faint sounds around him until they stopped. No sirens. No rotors. Just silence. The day would be marked in Alaskan history as one of the state’s most deadly aviation tragedies.

But it was no freak accident.

A Billionaire

56-year-old Petr Kellner was more than just the wealthiest man in Czechia. He was a defining figure of the country’s post-communist era—an investor who capitalized early and built PPF Group into a sprawling conglomerate with holdings in finance, real estate, media, and telecommunications. At the time of his death, Kellner’s net worth was estimated at over $17 billion. He was known for being intensely private, even as his influence stretched across Europe and Asia.

After his death, control of PPF passed to his wife, Renáta Kellnerová, and their children, making her one of the wealthiest women in Europe. The Kellner family maintained silence in the months following the crash, eventually settling with the companies involved. After the incident, two federal court filings in Anchorage released in 2022 show that it is probable that Kellner and another member of the crew, likely lead guide Gregory Harms, did not die right away when the helicopter crashed. They likely “died while waiting for rescue,” according to filings in a U.S. District Court case involving a settlement between the sole survivor, David Horvath, and Soloy Helicopters. The rescue came several hours too late.

The Day’s Plan

An NTSB report filed by investigator Joshua Cawthra in September 2023—over two years since the crash—shows that Soloy Helicopters had been contracted to fly guests of Tordrillo Mountain Lodge, a luxury heli-ski operation catering to a wealthy, international clientele. That Saturday, the plan was simple: several ski runs in the Chugach backcountry, then return to the lodge before sunset in time for a gourmet dinner.

The helicopter left Wasilla around 2:50 p.m. The report shows that the weather wasn’t perfect, but it wasn’t terrible, either: some gusty wind, light snow, and flat light. Over the next few hours, the group completed six successful ski runs.

At about 6:30 p.m., they headed for their last run of the day.

“Little White Room”

As the helicopter approached a ridgeline to perform a landing at roughly 6,266 feet elevation, visibility deteriorated. According to the survivor’s testimony, the aircraft suddenly entered what he described as a “little white room”—a total whiteout. That’s not unusual in heli-skiing. Powder snow stirred up by the rotor wash can quickly eliminate all visual cues.

The report states that the pilot tried to adjust. The helicopter began moving backward, rapidly. Moments later, it slammed into the ridge, then rolled nearly 900 feet down the slope.

The emergency beacon activated. Yet there was no immediate response. In fact, rescue would not arrive at the crash site until almost five hours after impact.

The Pilot’s Training—Or Lack Thereof

The report found that Zachary Russell had logged more than 3,200 hours of helicopter flight time. He was 33 years old and considered competent by his employer. However, after the crash, a closer examination of his training revealed significant gaps.

Russell hadn’t received proper training in inadvertent instrument meteorological conditions, or IIMC—what pilots experience when they suddenly lose visibility and have to rely on instruments to stay oriented. According to the NTSB, he also hadn’t been formally trained for ridge landings in the AS350-B3, the helicopter he was flying that day—or in the previous model he had flown and trained on. Soloy’s own training materials didn’t include modules for either scenario. Yet Russell was cleared to fly. The NTSB put it plainly: “It is likely that the pilot did not meet the qualification standards to be the pilot-in-command of the accident flight.”

The FAA’s Principal Operations Inspector who was responsible for overseeing Soloy (whose name was not shared in the report) had previously worked for the company as a pilot. Between 2011 and 2013, she was Soloy’s chief pilot and also worked at another helicopter company with the person who later became the president of Soloy, according to the NTSB. The investigation found that she approved the training program despite these omissions and had not observed any of the company’s heli-ski flights during her time as inspector. The NTSB officially determined it to be “inadequate oversight of the accident operator” but that there was insufficient evidence to determine whether the inspector’s prior work history was a factor.

The NTSB would later conclude that Russell’s lack of IIMC training “likely contributed” to the crash. When visibility disappeared, he didn’t transition to instrument flying. He lost situational awareness which led to impact. But it wasn’t necessarily a bad call by Russel that sealed their fate; the investigation concluded that gaps in training likely contributed to the crash, even though at the time he was approved to pilot the aircraft.

Rescue Delayed

There’s evidence that at least two other passengers survived the crash for up to two hours. This includes Kellner and Harms. But no distress call was made.

Flight-following—the job of tracking the helicopter and initiating rescue if needed—had been informally assigned to the lodge. The task fell to a ski guide using a Garmin inReach satellite tracker. The last signal from the helicopter came at 6:36 p.m.

By 7:15 p.m., the guide back at the lodge reported that there had been no contact for over an hour. But instead of calling for help, the report states that the lodge staff checked in with another heli-ski company, which mistakenly said the helicopter was on its way back.

It wasn’t until 8:25 p.m. that Soloy was notified that something was wrong. Only then did the company begin activating its emergency plan. The wreckage was finally located around 11:30 p.m. The sole survivor, David Horvath, was evacuated more than five hours after the crash.

The Sole Survivor

David Horvath, a 48-year-old Czech national and longtime associate of Kellner, was seated in the back of the helicopter. When the aircraft came to rest, he was trapped, partially buried in snow, his body wedged between the other passengers.

His testimony states that he could hear someone else outside of the helicopter—likely Kellner or Harms—making faint noises. They communicated briefly, but then, after a while, the other passenger stopped responding. After that there was only silence.

By the time rescuers reached the site, Horvath was hypothermic and suffering from advanced frostbite. He saw the light of the approaching helicopter and then reportedly passed out, not remembering anything else until he woke up in the hospital later. Horvath managed to survive, but he lost most of his fingers and now lives with lasting injuries.

The Guide and the Toxicology Report

Toxicology results released by the NTSB revealed that Gregory Harms, the 52-year-old lead guide on board, had significant concentrations of amphetamine, cocaine, and 1,000 ng/mL of benzoylecgonine—a primary cocaine metabolite—in his blood at the time of the crash. According to a 2022 review of drug-impaired driving thresholds, legal cut-offs for amphetamine in blood typically start at 20 ng/mL, with upper enforcement thresholds reaching 600 ng/mL, depending on jurisdiction. For cocaine, cutoff levels range from 10 to 80 ng/mL. Benzoylecgonine, which lingers longer in the bloodstream, is considered elevated at levels as low as 50–100 ng/mL.

A concentration of 1,000 ng/mL in blood—not urine—is regarded as exceptionally high, often indicative of recent heavy or binge use. This level of exposure suggests that Harms had used cocaine within the prior 24 hours, and not casually. While the NTSB does not make medical diagnoses, toxicology data at this scale points to substantial, acute drug use, well beyond what would be considered recreational.

Harms played a central safety role during the flight—helping to identify landing zones, assess snowpack conditions, and communicate with the pilot. Impairment in those areas can have serious operational consequences, especially in rapidly changing mountain environments where judgment and coordination are critical.

“Although ski guides are not considered crewmembers according to the Federal Aviation Regulations, they have safety-related responsibilities during heli-ski flights such as coordinating with pilots about landing and pickup zones and assisting pilots with hazard and pickup zone identification. However, investigation was unable to determine whether the guide’s illicit drug use played a role in the accident,” the NTSB report reads.

Tordrillo Mountain Lodge’s handbook specifically states that guides cannot be under the influence while working. The NTSB also noted that 38-year-old Sean McManamy, the second guide aboard and a resident of Girdwood, Alaska, tested positive for THC. However, the levels found were considered non-impairing, and his role in the flight’s outcome was not linked to the crash.

While McManamy is believed to have died on impact, Harms may have initially survived. A civil lawsuit filed in U.S. District Court in 2022 claims that Harms survived the initial crash but suffered severe injuries that ultimately proved fatal, raising questions about whether a faster rescue could have made a difference.

Institutional Failures

The investigation reveals that Soloy Helicopters’ operations manual didn’t include adequate procedures for flight locating or overdue aircraft. Soloy’s director of operations admitted in the official investigation that he didn’t know when the helicopter was due back that evening.

The FAA inspector who approved the company’s training program did not confirm that it met federal standards. She didn’t ensure pilots were being trained on key safety procedures like whiteout recovery or ridge landings.

Soloy’s emergency response plan was expected to follow FAA Order 8900.1, which requires that search and rescue be notified if an aircraft has not been heard from within 30 minutes of its last expected check-in. That didn’t happen. Instead, there was a prolonged period of uncertainty, with staff at Tordrillo Mountain Lodge checking in with another heli-ski operator and mistakenly concluding the aircraft was en route. The delay in alerting authorities cost precious time—time that may have made a difference for those who initially survived the crash. Soloy was later found by the NTSB to not have incorporated these requirements into its flight locating procedures.

Every point in the system—operator, regulator, contractor—missed something. And taken together, those misses added up.

Legal and Corporate Consequences

After the crash, Kellner’s family filed wrongful death lawsuits. Soloy and Tordrillo Mountain Lodge settled out of court. The FAA did not issue public sanctions. No criminal charges were filed.

PPF Group, the multinational firm founded by Kellner, passed into the control of his wife and children. Business continued. But for the families of those lost, and for the lone survivor, the impact of that day remains.

Lessons From the Glacier

The crash near Knik Glacier wasn’t caused by one erroneous decision. The report shows that it was the result of many small shortcomings in training, oversight, communication, and accountability. Each gap made the next one more dangerous. The NTSB determined the probable cause(s) of the accident to be:

“The pilot’s failure to adequately respond to an encounter with whiteout conditions, which resulted in the helicopter’s collision with terrain. Contributing to the accident was the (1) operator’s inadequate pilot training program and pilot competency checks, which failed to evaluate pilot skill during an encounter with inadvertent instrument meteorological conditions, and (2) the Federal Aviation Administration principal operations inspector’s insufficient oversight of the operator, including their approval of the operator’s pilot training program without ensuring that it met requirements. Contributing to the severity of the surviving passenger’s injuries was the delayed notification of search and rescue organizations.”

The investigation shows that these weren’t just flaws, but failures of responsibility. Safety was not ensured by those who were entrusted to do so. The FAA signed off on incomplete training programs. Soloy certified a pilot without confirming he could handle whiteout conditions. The lodge relied on informal tracking for flights operating in remote, avalanche-prone mountains and ultimately received inaccurate information that the downed helicopter was inbound. Though protocols were established, the lack of timely follow-up meant the helicopter’s location remained unknown for hours—delaying rescue and worsening survivability.

There is a broader lesson here from this tragic incident that reaches beyond aviation and heli-ski operators. One that teaches that when safety is decentralized and assumed rather than verified, things can fall through the cracks. When oversight becomes familiar instead of rigorous, mistakes can go unchecked. And when emergency protocols exist only on paper, they don’t help anyone when it matters—and the price to be paid is high.

Evidence shows that everyone on that helicopter trusted the system around them—the pilots, the guides, the lodge, the regulator. But it’s possible that trust was misplaced. Heli-skiing will never be without risk. That’s part of its appeal. But through the application of various control systems, the risks can be managed. The required skills can be met through extensive training. Communication can be structured to be effective in any situation. Rescue can be fast. Unfortunately, though, as in the case of the Knik Glacier helicopter crash, the NTSB investigation identified multiple lapses in these systems that were supposed to reduce danger; in this case, they were handled more like suggestions instead of standards. According to investigators, the wind or the snow didn’t cause the crash, but a series of key, overlooked factors—meaning that this likely could have been prevented.

In aviation clarity is everything. It’s what keeps people alive. When it comes to tragedies, understanding the mistakes made, learning from them, and operating with responsibility moving forward are the only paths that can provide real growth. In the case of the Knik Glacier helicopter crash, they won’t bring anyone back. But perhaps they can stop something like this from ever happening again.