No matter where you live, ski or venture into the mountain, it is very likely that you are well aware and concerned about avalanches. You might have only heard of them or seen them on the distance. You might, as well, have experienced them in first person, having a mass of sliding snow affecting you, your house, your car, or your backcountry/mountaineering partners.

As the winter season approaches the rumor of the so-called avalanche season gets louder. Precipitations, the decreased temperatures, and snow brought by the colder months of the year attract an important portion of people to the mountain areas. Those three factors also create the perfect scenario for snowy slopes to be potentially dangerous. As a result, avalanches start happening more. A lot more.

But the truth is that avalanche season never actually stops. As long as there is snow on a slope, there is a chance it will slide. And it does, avalanches happen year-round and are triggered in different circumstances. We just happen to be more exposed and aware of them during the winter. Avalanche season is as real as a ski season is: it can last all year, but is a lot more active during winter.

However, there is another concept that underlies beneath the whole avalanche phenomenology: The Avalanche Cycles.

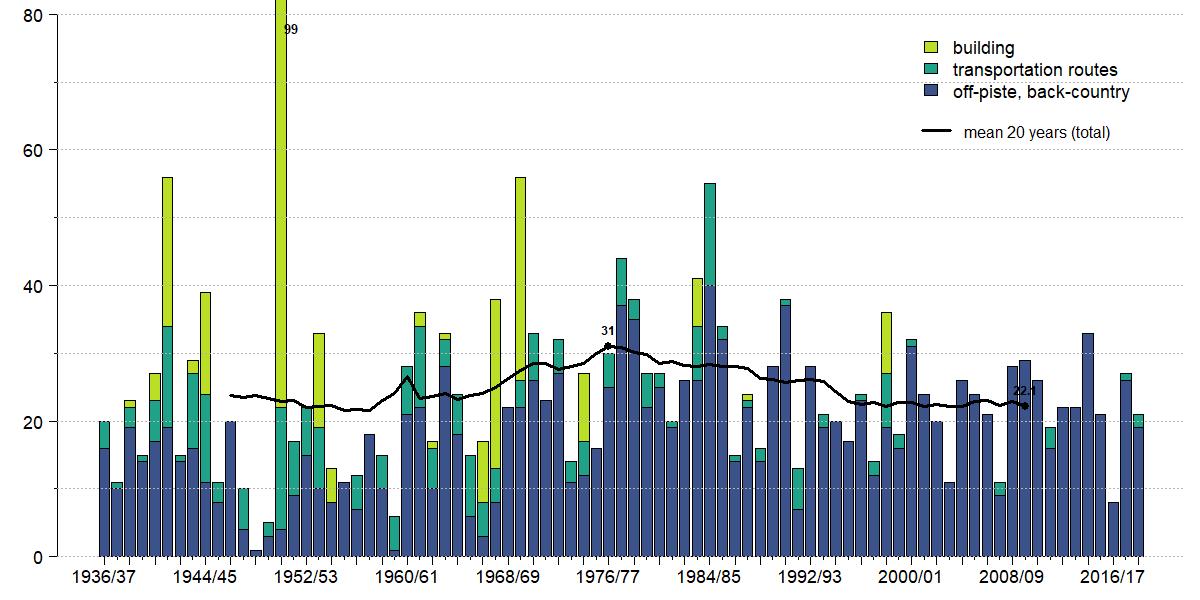

Every once in a while, there are winters that see a lot more avalanches than usual. During the winter of 1950/1951, in the Austrian Alps, there were a total of 135 fatalities due to avalanche related accidents. In the previous years, the number of fatalities was far below, reaching no more than twenty.

Three years later, during the winter of 1953/1954, the fatalities reached once again a very high number, a total of 143 dead people. About one-third of the avalanches were catastrophic, meaning that they affected developed and urban areas.

Last winter in the Rocky Mountains there was an unprecedented amount of big, destructive avalanches, ranked 4 to 5 on a 1-5 scale. In a two week period time, 87 avalanches in that size range were registered, while only 24 had been recorded in the eight previous years. It’s important to mention that the 2018-19 winter itself wasn’t necessarily record-breaking in terms of snowfall, it was just unprecedented in its destruction.

Situations like this happen in mountains all around the world, years where the avalanche activity is considerably higher than usual, but other factors like snowfall or people going on the mountains are still the same. Those circumstances can be explained by the year’s avalanche cycle.

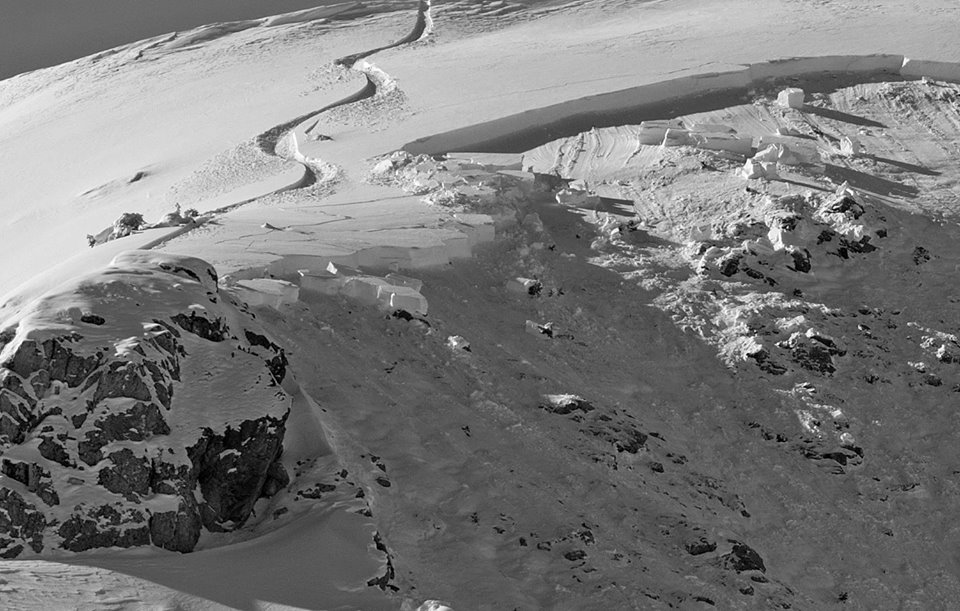

An avalanche cycle is a unique combination of several climatic parameters that can happen every once in a while. Large areas of unstable layers develop in the mountains snowpack due to weather circumstances over a long period of time. This causes the snow to be susceptible to avalanches that can occur over wide areas and on isolated, unexpected moments.

When this condition develops, the number of deaths and property damage caused by avalanches increases significantly, even changing the nature of the terrain in some places.

“A big (avalanche) cycle like this really doesn’t happen from a one event. And in this case, there were three events over the course of the whole winter that led up to this event in early March.” Ethan Greene, director of CAIC, on last winters avalanche cycle.

Avalanche cycles have been a big hazard to everyone in mountain environments. A major avalanche cycle in Turkey killed nearly 300 people in 1992. If prior warning of the situation could have existed, hundreds of lives would have been saved.

But the likelihood of accidents by a major avalanche cycle in places like Europe and North America has been reduced since the mid-1990s because of rigorous avalanche studies, prediction, warning, and control programs.

A study made in Innsbruck, Austria, by Peter Höller and the Federal Research Centre for Forests Department and Natural Hazards, showed a strong relationship between certain weather situations and avalanche cycles. Two-thirds of all investigated avalanche cycles were influenced by northwesterly oriented frontal zone climatic events.

Last season’s avalanche activity in Colorado responded to a climate produced avalanche cycle. The early season snow, in October, covered most faces above treeline. That snow turned into a very weak layer of snow right at the bottom of the snowpack, affected by inconsistent temperatures.

Then, during January and February, many not so big, regular snow events created a very strong layer of snow on top of the early season, weak layer.

Finally came March with lots of precipitation in a short period of time, overloading the snowpack and causing it to break big time.

The moral of the story is that avalanches respond to a sum of conditions through a vast period of time that can create the perfect case scenario for disaster. It is not only about the last snowfall, the inclination of the slope, the avalanche paths that can be seen, or the wind loaded faces. There is a lot underlying, that if we are not aware of can end up in a tragedy.

Wet-snow avalanches threaten mountain communities, but many times their formation, as well as the snowpack processes leading to wet-snow instability, are poorly understood. There are infinite factors affecting, creating unknown and unprecedented situations like the one experienced last season in Colorado.

That’s why studying and being informed is the ultimate weapon to stay alive out there.

Be safe out there ma man

really interesting, thanks for the information