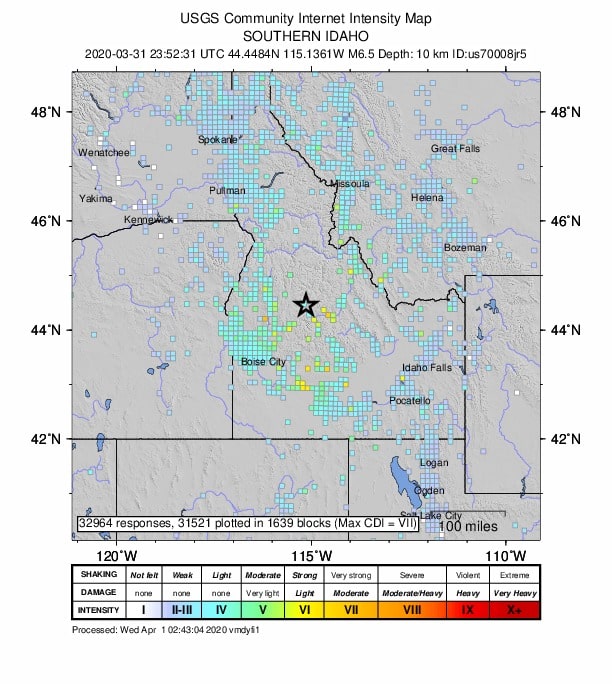

On March 31, 2020, at precisely 5:52 pm central Idaho was rocked by a magnitude 6.5 earthquake. The quake was the second-largest ever recorded in the state. The largest temblor in Idaho’s history was the Borah Peak earthquake in 1983 which registered as a magnitude 6.9. The questions geologists are asking of the March 31st quake is why was it so big and why was it located where it was?

Idaho’s Geology

Generally, Idaho is a seismically inactive area with earthquakes larger than a magnitude 3 rarely occurring. However, central and southern Idaho are part of the Basin and Range Province. This area is slowly being pulled in an east-west direction as the North American and Pacific plates move away from each other. This leads to occasional shaking along Idaho’s faults mostly located in the south/central portion of the state.

The Sawtooth fault running through Central Idaho is named for the mountains that lie above it. Professor Glenn Thackray from Idaho State University discovered the fault only a decade ago. It was believed to be active, but no one had observed its activity. Since the epicenter of the March 31st earthquake was 16 miles north of the Sawtooth fault Thackray thought there must be a connection.

Gathering Evidence

As soon as the ground stopped shaking geologists started collecting data. Due to the low population density of central Idaho, there are not as many seismometers as geologists would like. The solution was that a team of local geologists deployed an additional 30+ seismometers around the area to record all of the aftershocks. Their aftershock data was consistent with Thackray’s belief that the Sawtooth fault might extend farther north than he originally thought.

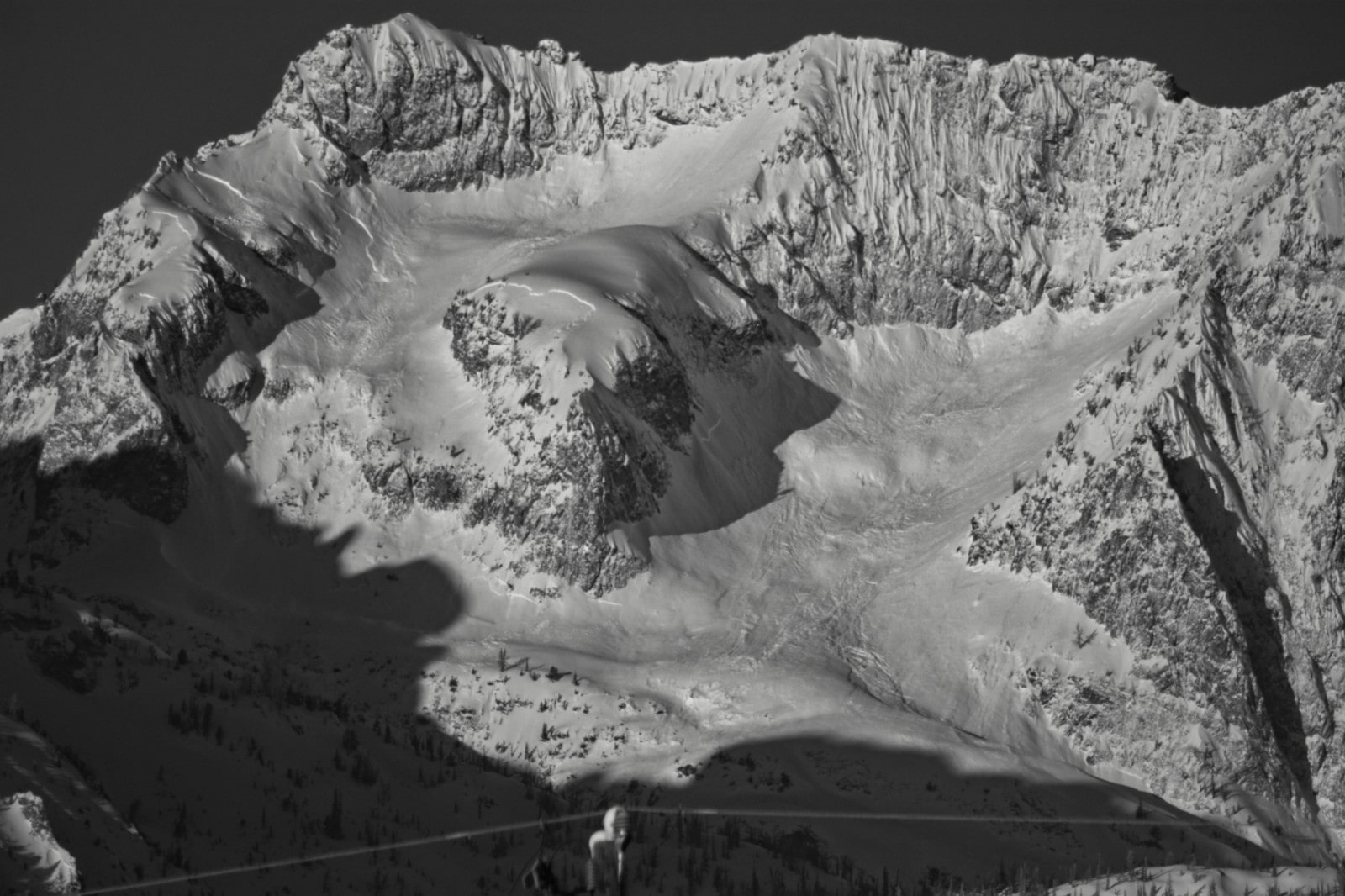

As the snow melted from the Sawtooth Mountains geologists were able to find more clues to piece the puzzle together. Stanley Lake, located close to the epicenter of the initial event had a beach prior to the earthquake. Once the snow and ice melted from the lake, it was clear it had experienced liquefaction. This rarely observed process occurs when sediment is shaken and temporarily acts as a fluid. Studying the liquefaction along with the thousands of aftershocks that occurred enabled geologists to start painting a picture of what actually took place.

Aftermath Observations

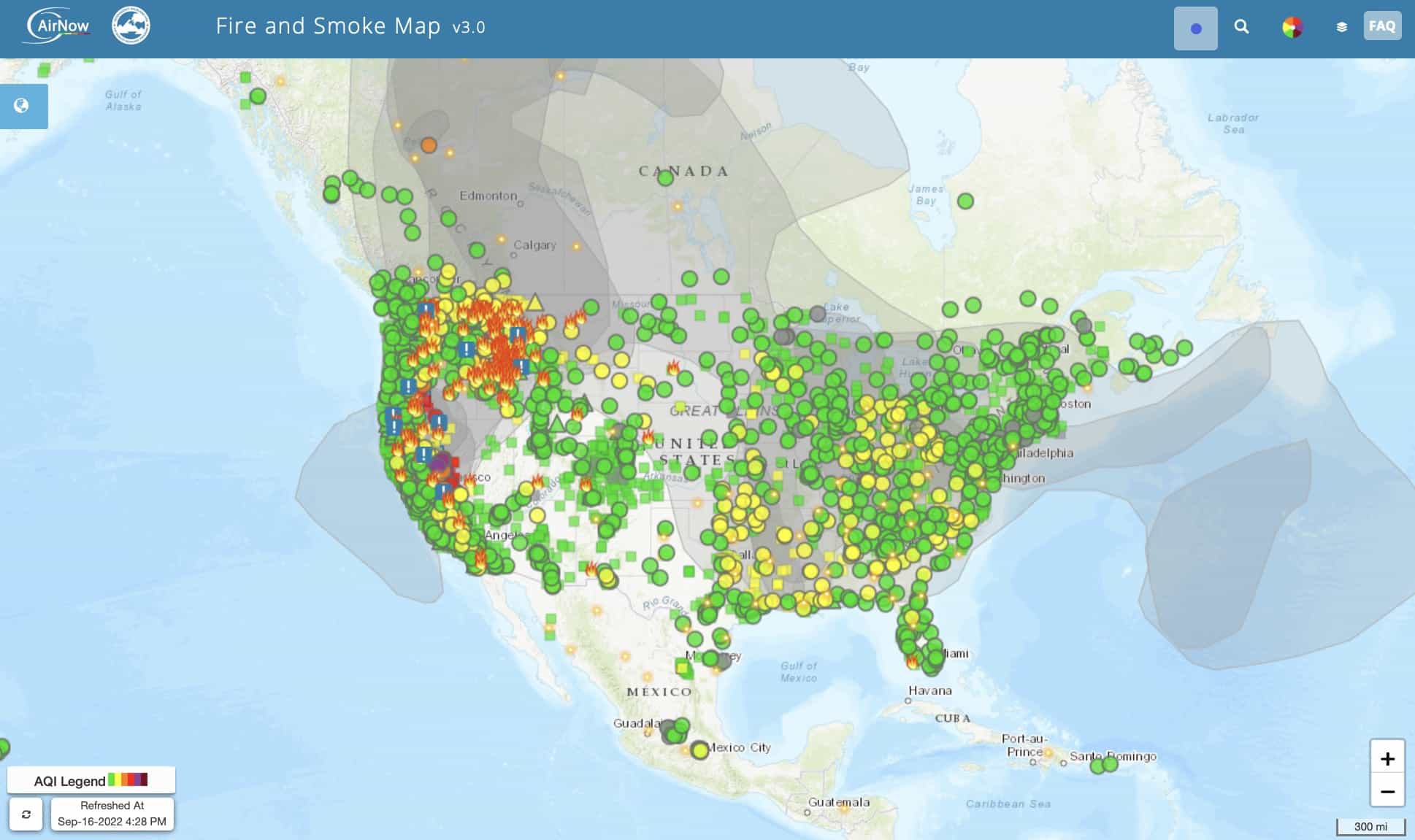

Since the initial earthquake, there have been thousands of aftershocks recorded. While most of them have been quite small, there has been a handful that were greater than an M4.0. Besides the liquefaction that was observed at Stanley Lake, other parts of Idaho have been affected. It is believed that the aftershocks played a role in a large rockfall that closed US Route 95 just south of Riggins, ID. Several rock spires have also collapsed due to aftershocks. In addition, widespread avalanche activity was noted immediately after the initial event.

While geologists still do not fully understand the mechanics behind the March 31 earthquake they are learning more every day. According to the United States Geologic Survey (USGS), there is unlikely to be another M6.0 or larger earthquake in the near future. However, depending on the energy released from the Sawtooth fault or one of the many others in the area Idaho could see many more substantial earthquakes in the months and years to come.