A Polish woman went unconscious and then passed away last month in the middle of a mountaineering expedition in Manaslu, Nepal. Earlier this year, many climbers attempting to summit Mount Everest lost consciousness and perished on the way to the top. Similar situations happen every year in mountains all around the world. The reason? High Altitude Sickness or Acute Mountain Sickness. What is this dangerous condition that affects even the most trained mountain athletes?

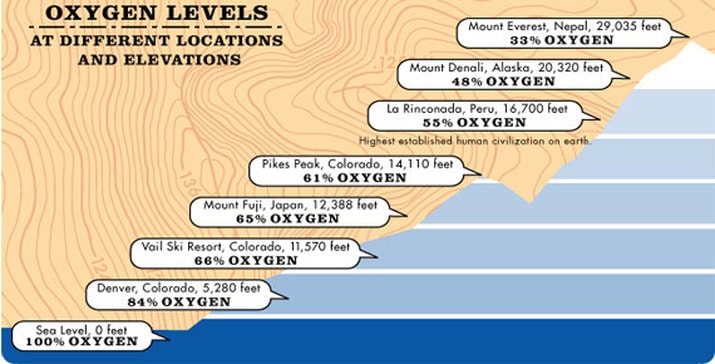

The growing popularity of mountain-related activities such as hiking, climbing, skiing, and snowboarding, has increased the amount of people visiting the mountain. Many of them are new to this environment while others are well trained and familiar with it, but no matter who you are, whenever you go into high terrain you are exposed to suffer from Altitude Sickness, and you should be aware of it. Altitude sickness occurs when people ascend to high altitude too quickly and the body does not adapt well to the lack of oxygen present at higher altitudes.

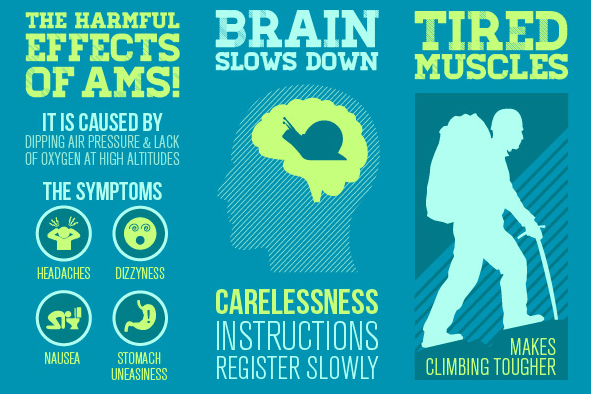

The Altitude sickness can present itself in three different ways. The first one is mild altitude sickness, known as Acute Mountain Sickness or AMS, and feels a lot like a hangover. Symptoms may include: Headache that is not relieved with common pain medicine, nausea, dizziness, fatigue, difficulty sleeping and a loss of appetite. Some people get them all, others just a few, so it is important to keep a record on how you feel during the ascent.

Acute mountain sickness is the least dangerous of several kinds of altitude illnesses that can occur. This sickness affects almost 50% of all people who go from sea level (or near) up to 8.000 feet (2.500 meters) or more of elevation without scheduling enough rest time. That’s why if you are feeling any of the symptoms listed above, and you plan to keep on climbing higher, you might be subject to develop one or both of the other more dangerous forms of altitude sickness: HAPE and HACE.

HAPE stands for High-Altitude Pulmonary Edema and HACE stands for High-Altitude Cerebral Edema. Ascending faster than 1.640 ft (500 m) per day, and exercising vigourously are two factors that can produce AMS and result in a HAPE or HACE.

HAPE, which is the lungs’ response to an increase in altitude, creates higher pressure in the lung arteries. This causes fluid to leak from the blood vessels into the lungs. Symptoms of high-altitude pulmonary edema commonly appear at night and can worsen during exertion. Symptoms of HAPE include:

- Chest tightness,

- Coughing and making noises when breathing, such as rattling or gurgling sounds.

- Extreme fatigue

- Inability to catch your breath, even when resting

*As an advice, you should ALWAYS be able to catch your breath when resting. And if you have had HAPE before you are a lot more likely to develop it again.

HACE is considered by many experts to be an extreme form of acute mountain sickness. HACE is fluid on the brain due to malfunctions from having low quantities of oxygen in the blood. It causes confusion, clumsiness, and stumbling. The first signs may be uncharacteristic behavior such as laziness, excessive emotion or violence. A person suffering from this condition may not understand that symptoms have become more severe until a traveling companion notices unusual behavior. Drowsiness and loss of consciousness occur shortly before death. Symptoms include:

- Worsening headache and vomiting

- Confusion

- Walking with a staggering gait

- Visual hallucinations

- Exhaustion

- Changes in the ability to think

“According to a study made by the GMERS Medical College of India, the estimated incidence of HAPE in visitors to ski resorts in the Rocky Mountains of Colorado is less than 0.1%. In a general alpine mountaineering population, HAPE is around 0.2%. The HAPE incidence among trekkers in the Himalayas and climbers in the Alps ascending at a rate of over 600 meters (1960 ft) a day is around 4%. Indian soldiers, airlifted to an altitude of 5.500m was associated with a HAPE incidence of up to 15%”

Prevention

Gradual changes in altitude will help your body adapt to the low-oxygen environment and can reduce your chances of developing all forms of altitude sickness. People adapt at different rates, but there are four general guidelines for climbing above 10,000 feet that are practical for climbers to follow:

- Do not increase your altitude by more than 1,640 feet (500 meters) per night.

- Limit your physical exertion to reasonable levels during your first few days of ascent to altitude.

- Each time you increase your altitude by 3,000 feet (900 meters) spend a second night at this elevation before going farther.

- Drink plenty of fluid during your altitude exposure

If you are feeling the symptoms:

The first rule of treatment for mild symptoms of acute mountain sickness is to stop ascending until your symptoms are completely gone. If you have more severe symptoms or any symptoms of HACE, HAPE, or blurred vision, you need to move to a lower altitude as soon as possible. If you remain at your current altitude or continue going higher, the symptoms will get worse and the sickness can be fatal.

Besides moving to a lower altitude, you can treat mild altitude sickness with rest and pain relievers. The drug acetazolamide can speed recovery balancing your body chemistry and stimulating breathing.

If you have symptoms of altitude sickness, avoid alcohol, sleeping pills, and narcotic pain medications. All of these can slow your breathing, which is extremely dangerous in low-oxygen conditions.

If a descent must be delayed — you can treat high-altitude cerebral edema with supplemental oxygen and the drug dexamethasone, which decreases brain swelling.

But at the end of the day, descending is the best way to avoid any fatal outcome or scenario.

This article is incredibly informative! Altitude sickness is often underestimated, and it’s eye-opening to understand how quickly it can escalate. The prevention tips are practical and a must-know for anyone planning high-altitude adventures. Thanks for spreading awareness!

Wow, this is an eye-opening read! Altitude sickness is no joke, and it’s crazy how even experienced mountaineers can fall victim to it. The breakdown of AMS, HAPE, and HACE is super helpful—especially the early symptoms to watch out for. Prevention tips like gradual ascent and hydration are a must-know for anyone heading to high altitudes. Thanks for sharing such crucial info!