After three years of moderate La Niña winters, El Niño is poised to return in full force, having major implications for the North American ski season. Let’s look at what El Niño is, how it works, and the impact it will have on snowfall this season.

- Related: Farmers’ Almanac 2023/24 Winter Forecast: A Return Of Traditional Winter Weather: The Brrr Is Back!

As of August 2023, El Niño conditions have developed, with the NOAA giving it a probability of greater than 95 percent of lasting through the winter. This number is derived from various physical models forecasting global circulations and feedback mechanisms months in advance. Groups of these models, called ensembles, give us an idea of confidence and certainty when making a forecast. In this case, we are confident that El Niño will persist into the spring.

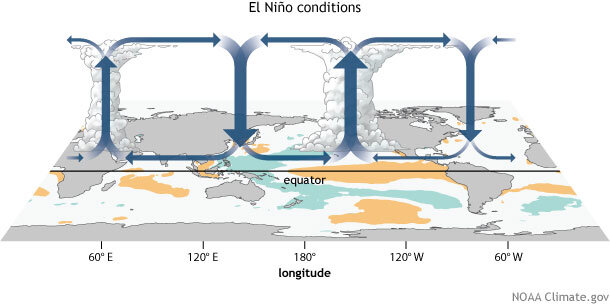

What exactly is El Niño? El Niño leads to shifts in the global atmospheric flow, subsequently impacting weather and climatic trends all around the planet. At its core is the Walker circulation, an atmospheric sequence over the equatorial Pacific. As El Niño sets in, warmer-than-normal sea surface temperatures in the Eastern Pacific Ocean disrupt this circulation, intensifying rainfall and convection in the central and eastern Pacific. The trade winds relax, leading to further surface warming, a critical feedback mechanism indicative of El Niño. Recent observations have revealed signs of a weakened Walker circulation, marked by softer trade winds in the western Pacific and heightened cloudiness and rain in the equatorial region.

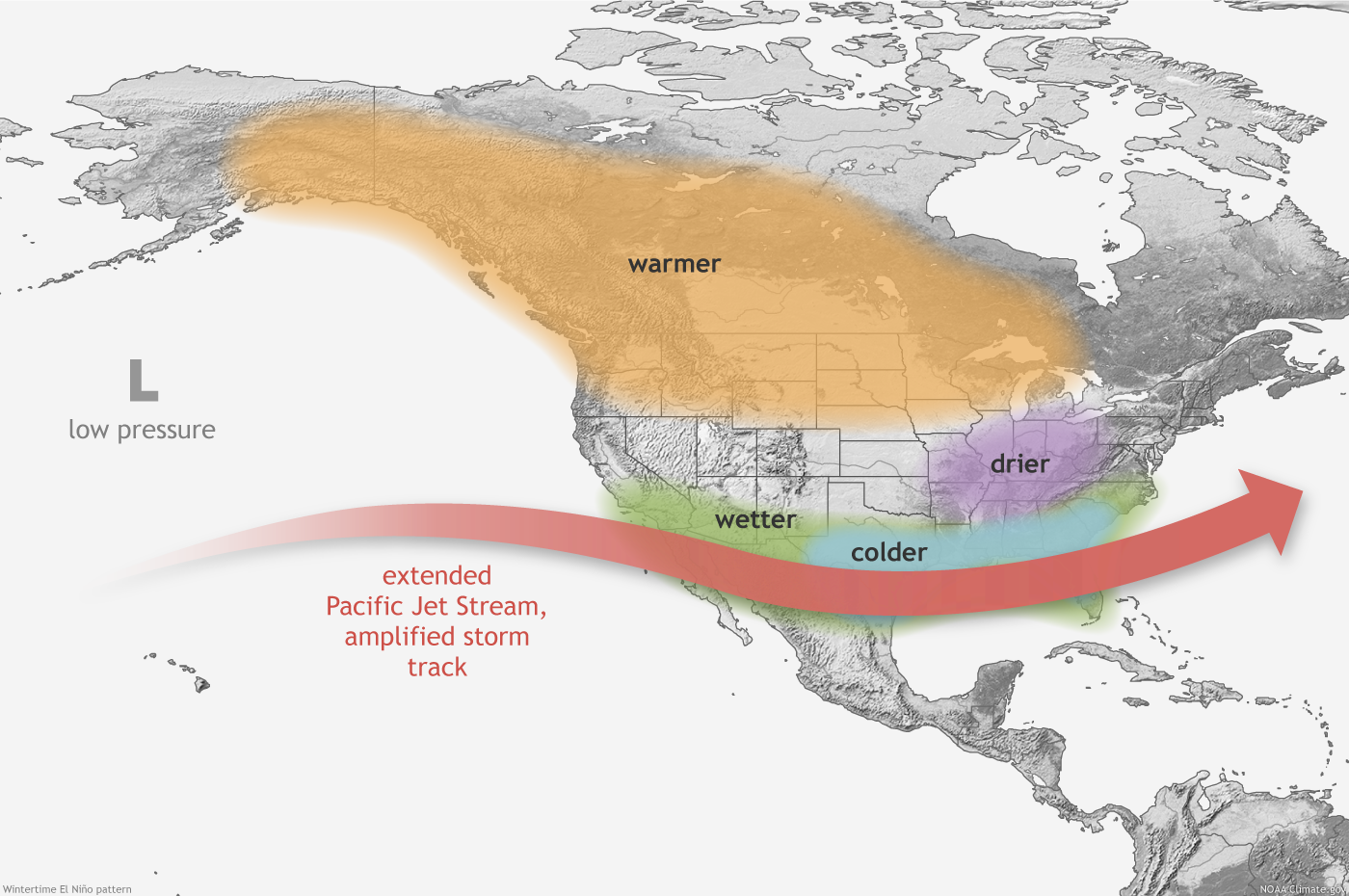

For the US, El Niño instigates alterations in tropical rain and wind patterns with global repercussions. The most notable effect is on the mid-latitude jet stream. These upper-atmospheric winds are instrumental in distinguishing warm from cold air masses and directing Pacific storms over the US. El Niño-induced weather patterns differ from those during La Niña; generally speaking, they tend to be opposite. However, El Niño’s impact on the US winter climate tends to be more probabilistic than certain, with each event exhibiting unique characteristics that are difficult to predict and assign analogs to.

Such alterations in the atmospheric flow can significantly affect the upcoming ski season in North America. Recognizing that conditions might evolve before winter, we can make preliminary forecasts based on present El Niño trends.

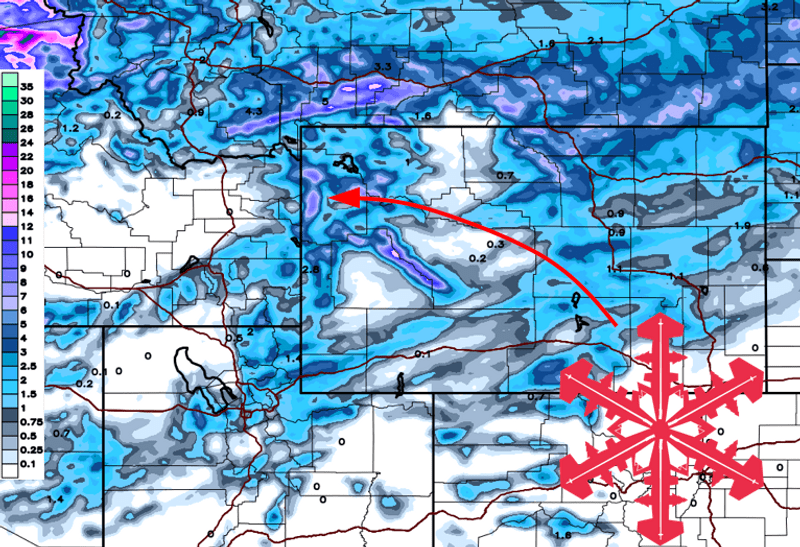

Generally, El Niño seasons see the storm track veering more to the south in North America due to a southerly dive in the jet stream. Assuming El Niño amplifies as anticipated, ski destinations in the southern Rockies (like New Mexico, Arizona, southern Colorado, and Utah) and the Southeast (like North Carolina) may witness above-average snowfall, courtesy of this southern storm path. California resorts will likely also enjoy enhanced precipitation. California is essentially North America’s “first defense” against southerly El Niño storm systems, meaning California is the most likely region to see above-average conditions. Central Rockies zones, encompassing central Utah and parts of Colorado, might not be as profoundly affected, given their position amidst these climatic shifts. Further inland is often a tossup, and the season could go either way. Generally speaking, El Niño will bring above-average precipitation for at least Southern Utah and Southern Colorado, but that influence could creep further north into Northern Utah and Northern Colorado.

Conversely, ski locations in the northern Rockies and the Pacific Northwest will likely see diminished snowfall due to the jet stream’s modified route. It’s worth noting that a general trend of reduced snow doesn’t negate the possibility of significant snow events and cold air outbreaks during the season.

El Niño’s winter implications aren’t confined to the US. Ski areas in British Columbia and Alberta might face warmer and drier spells, possibly resulting in decreased snow.

Though rare, El Niño winters can sometimes yield increased snowfall in the Pacific Northwest and Northern Rockies. Such irregularities arise from intricate weather pattern interactions; no two El Niño episodes are identical. For example, the 2015-2016 winter witnessed an El Niño that brought above-average seasonal snowfall to these zones. Nonetheless, this isn’t a standard trend; other elements can alter these outcomes. The influence of El Niño on North American winter weather leans toward likelihood rather than assurance. Broadly, even with informed forecasts rooted in historical data and ongoing conditions, weather remains inherently uncertain; it’s hard to predict weather 48 hours in advance, let alone months in advance!

There are a few other things to note. First, there’s emerging scientific literature that long-range teleconnections (long-range patterns that can be used as long-term predictors of weather and climate), like ENSO, are losing predictive ability due to climate change. A perfect example was last season when La Niña was poised to bring dry conditions to California and wet conditions to the PNW. Instead, California got hammered all season, and the PNW was stuck with a very mild season. The same could easily happen this year. For all we know, the PNW could get slammed, and California could be left high and dry!

It’s also important to remember that ENSO is not the only thing that drives long-term weather patterns. The MJO, QBO, PDO, AO, and many other ways are also critical in determining the most probable long-term outcomes. Stay tuned for a forecast later this fall, where we break down all of the fall signals and their composite implications for the 2023-24 North American ski season!